- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: An imperial investment

- Article Subtitle: The fight for abused children at Fairbridge

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1959, David Hill, aged twelve, left England and sailed on the Strathaird to Australia with two of his three brothers. Like thousands of children before them the Hill boys were bound for a Fairbridge farm school. Like thousands of children before them, they had come from a poor background, with a struggling single mother who believed that Fairbridge would give her boys a better education and greater opportunities in life than she possibly could.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Jacqueline Kent reviews 'Reckoning: The forgotten children and their quest for justice' by David Hill

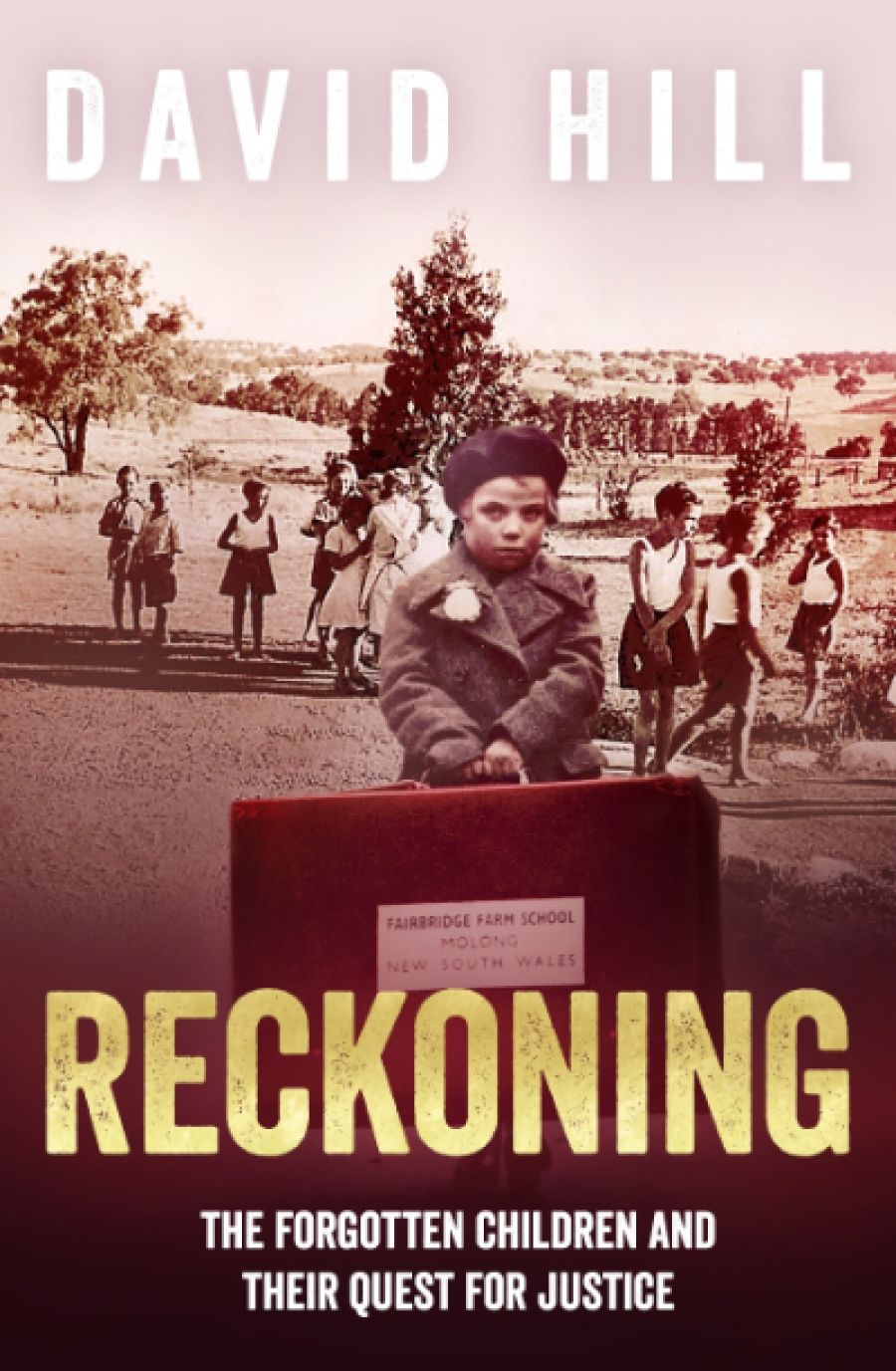

- Book 1 Title: Reckoning

- Book 1 Subtitle: The forgotten children and their quest for justice

- Book 1 Biblio: William Heinemann, $34.99 pb, 360 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/jW4eXM

The scheme, started by South African imperialist Kingsley Fairbridge in 1908, was based on two unpleasantly racial and class-based assumptions. The British colonies, he believed, needed to be populated by ‘white stock’ as agricultural workers, and the number of poor children in British cities was increasing, with little government or other help available for them. Why not solve both problems by outsourcing them? Slum children could be sent to Australia, Rhodesia, or Canada, escaping misery and poverty, and learning how to become farmers, rural workers, or farmers’ wives. Members of the British establishment found the idea immensely attractive. ‘This is not charity,’ declared Edward, the prince of Wales. ‘It is an imperial investment.’ In Australia two farm schools were set up; one in Pinjarra, Western Australia, in 1912, the other in Molong, western New South Wales, in 1938, where David Hill and his brothers went.

Reckoning is David Hill’s second book about his time in Molong: the first, The Forgotten Children, was published in 2007. Like several other published memoirs about life in Fairbridge schools (such as Ron Sinclair’s Fear and Friendships and John Lane’s Fairbridge Kid), Hill’s previous book concentrated on what he saw and endured during his two years in Molong, with quotes from other inmates. This new book covers much of the same ground. As his title suggests, Hill also describes the battle he fought along with other former Fairbridgeans, to bring to account the institutions that systematically ill-treated the children in their care.

David Hill (photograph via Penguin Random House)

David Hill (photograph via Penguin Random House)

Hill quietly sets out the history of this shocking abuse. On arrival at Molong, children were given threadbare, second-hand clothes, not always including shoes or underpants, and lived, segregated by sex, in cottage dormitories that were badly furnished, freezing in winter, and boiling in summer. Each cottage bathroom had two showers for fifteen inmates. The children were expected to work; children as young as four got up early and after an inadequate breakfast were sent to work in and around the property. They did go to local schools, but they were not encouraged to bother with homework, and the other local children shunned them. The only recreation was playing sport or mucking around by the local creek.

In charge of Molong was Frederick Woods, a huge South African with, said one inmate, ‘a rocky concreteness about him’. Woods was terrifying – not just because of his size, but because of his power. He was in charge of almost everything, organising rosters, hiring and firing staff, setting the rules, enforcing discipline, and dispensing punishment. His preferred way of doing the latter was flogging boys and girls with a broken hockey stick.

Woods was at the head of a choice array of sadistic psychopaths, men and women who gloried in cruelty to young children. One woman in charge of a cottage sought to cure bedwetting by plunging a young girl’s head into a toilet. Beatings were common: more severe, of course, if the child retaliated. Worse was the sexual abuse, and Hill does not stint on describing this. He even mentions war hero Sir William Slim (governor-general from 1953 to 1959), who, on a visit to Fairbridge, fondled young boys in the back of his vice-regal car. There were various half-hearted investigations into rumours of sexual abuse by cottage mothers and other Fairbridge adults, but nothing was ever done.

Hill admits that he got off lightly, being a bright and bolshie kid who, though he received his fair share of beatings, refused to be intimidated. (This may be why he would become an effective chairman and managing director of the ABC, as well as an executive in other positions, in later years.) Besides, unlike many of his contemporaries, Hill and his brothers left Fairbridge after only a couple of years and were reunited with their mother in Australia. Others were less fortunate. In one of this book’s most poignant chapters, titled ‘Every Childhood Lasts a Lifetime’, Hill uses the words of former inmates to demonstrate that few who endured the Fairbridge treatment emerged without debilitating and awful scars; in fact, Hill was probably one of the few who managed to overcome his experiences. Many, as adults, would have constant battles with depression, low self-esteem, and the inability to give or to receive love; others turned to drink and drugs, and several committed suicide. The descriptions of life at Molong – and its aftermath for so many – make Reckoning a tough read.

The last third of the book deals with the fight against the authorities responsible for the treatment of the Fairbridge children: a class action led by Hill and run in Australia by the law firm Slater & Gordon. Hill painstakingly delineates the ways in which government instrumentalities, especially in the United Kingdom, equivocated, stalled, and tried to evade responsibility. The implicit assumption by these authorities that disadvantaged children, the so-called dregs of society, deserved no better treatment than they had received is dispiriting. But this part of the book deals with legal and bureaucratic issues, and the pace necessarily flags. Hill’s restraint in chronicling the awfulness of Fairbridge has worked well: here, however, a more urgent sense of the sheer bloody-minded grind of seeking compensation would have been more effective. However, thanks to the work of the British government under prime ministers Gordon Brown and Theresa May, the Gillard and Rudd governments, and New South Wales Premier Mike Baird, justice was finally done: the Fairbridge victims received compensation from both the New South Wales and British governments, though as late as 2019, after eleven years of gruelling effort.

In telling the Fairbridge story, David Hill has not only drawn attention to a shameful episode in white Australian and British history but has shown that sometimes – against all odds – humanity and decency can prevail.

Comments powered by CComment