- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Environmental Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Inalienable vitality

- Article Subtitle: Amitav Ghosh’s entangled sensibilities

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Approximately 37,000 years ago, a volcano erupted in the south-east corner of the continent now known, in settler-colonial parlance, as Australia. His name is Budj Bim. As his lava spread and cooled, Budj Bim’s local relations, the Gunditjmara people, set about developing new ways of managing the changing landscape. They would engineer, most famously, a large and sophisticated aquaculture system, one dedicated in particular to the raising and harvesting of Kooyang, or eels. This infrastructure, explains Gunditjmara man Damein Bell, was instrumental in providing food to ‘one of the largest population settlements in Australia before Europeans arrived’.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

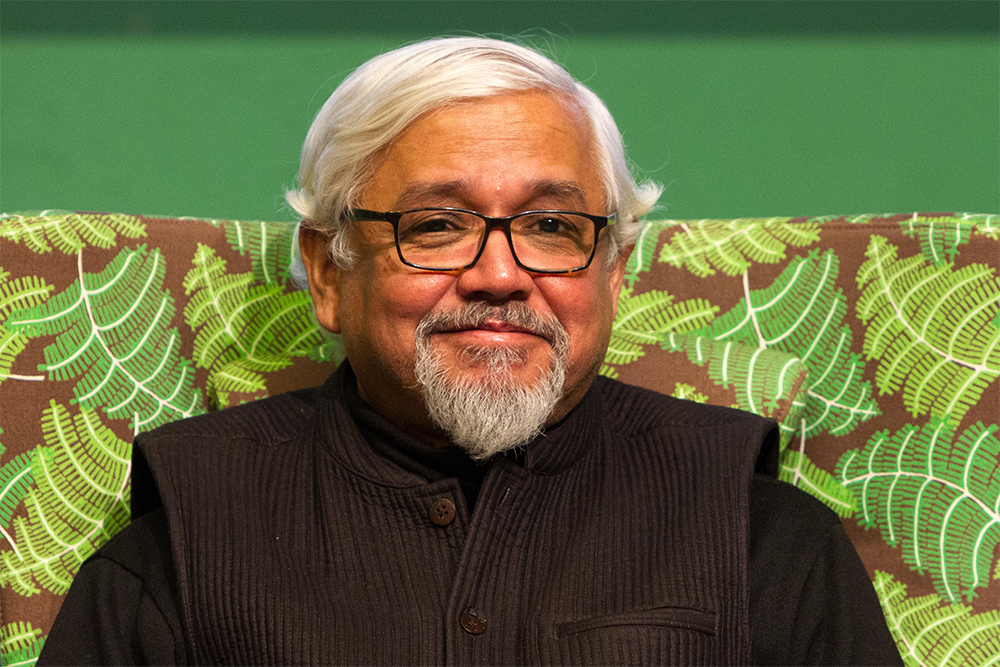

- Article Hero Image Caption: Amitav Ghosh, 2019 (photograph by Marco Destefanis/Pacific Press/Alamy)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Amitav Ghosh, 2019 (photograph by Marco Destefanis/Pacific Press/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Killian Quigley reviews 'The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a planet in crisis' by Amitav Ghosh

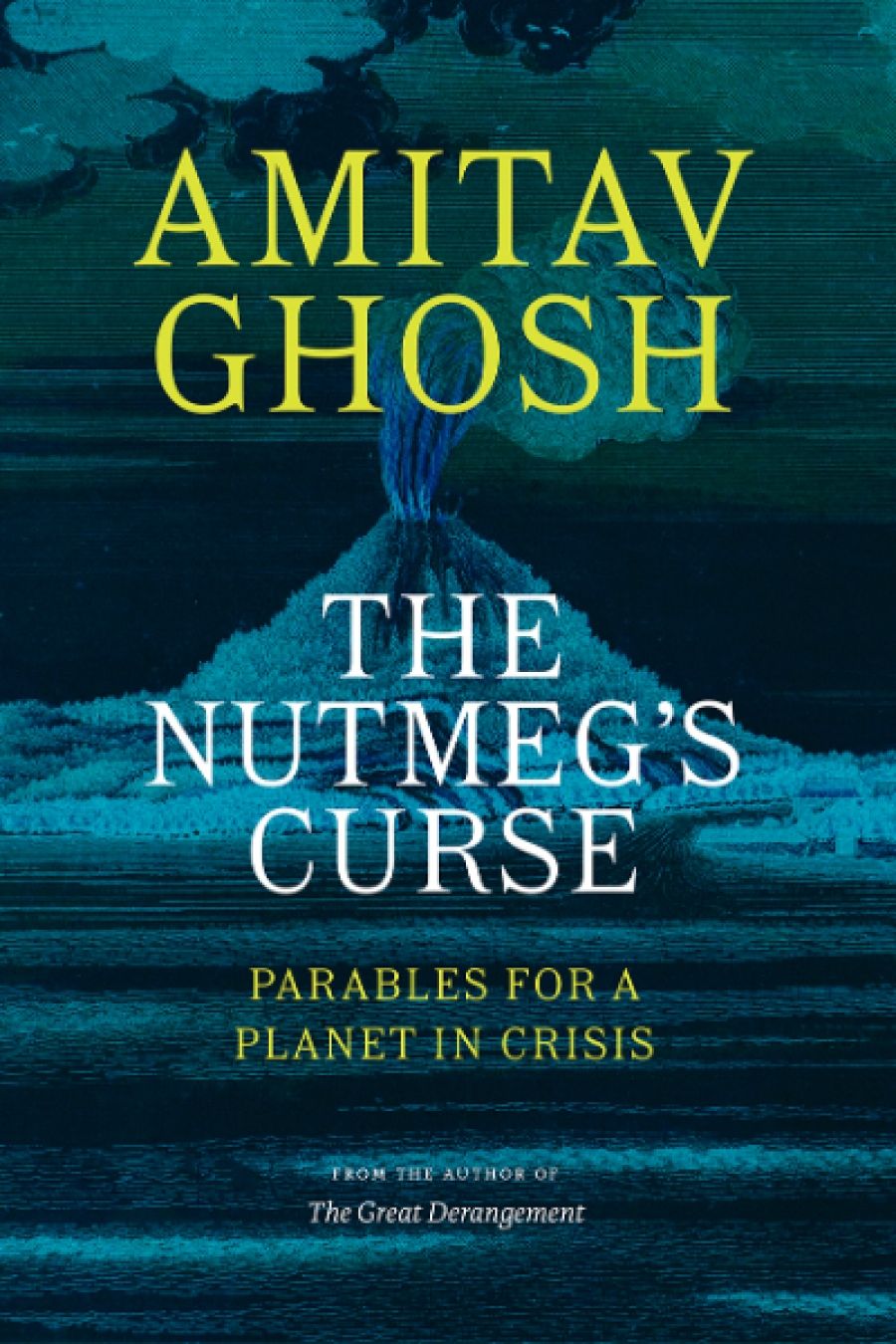

- Book 1 Title: The Nutmeg’s Curse

- Book 1 Subtitle: Parables for a planet in crisis

- Book 1 Biblio: John Murray, $32.99 pb, 339 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/dovOKW

For the prolific novelist, historian, and critic Amitav Ghosh, Budj Bim lies at the source not only of a phenomenally deep history of land management but of what may be ‘the oldest story to be passed down to modern times’. By emphasising as much, Ghosh is not recommending Budj Bim’s story for incorporation into some cabinet of narrative antiquities. On the contrary, he is drawing attention to the extraordinary integrity of Gunditjmara knowledge despite the disasters of colonisation and the inanities of ‘official modernity’. With his latest work of non-fiction, The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a planet in crisis, Ghosh lays blame for contemporary difficulties, firmly, at the feet of ‘Western settler-colonial culture’ – and looks beyond that culture for other, livelier stories through which to better comprehend our interwoven pasts, presents, and futures.

Ghosh’s book opens about four hundred years ago in the Banda Islands, part of a vast (and substantially volcanic) Indonesian archipelago called Maluku. Though numerically few and geographically small, the Bandas were pivotal sites for early modern commerce because they produced, incredibly, the entirety of the world’s nutmeg and mace. From at least as early as the 1500s, the Bandanese attracted the attention of European imperial powers like Portugal and Spain, who sought exclusive trading rights to the islands’ valuable spices. In the first decades of the seventeenth century, agents of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) established a tenuous foothold in the Bandas before deciding their business would be made easier if the locals would simply go away. On the night of 21 April 1621, one exceptionally paranoid VOC official, spooked perhaps by nothing more threatening than an upset lamp, sparked a period of violence so devastating both for the human and ‘other-than-human’ inhabitants of the Bandas as to merit, in Ghosh’s view, the name of genocide.

With The Great Derangement: Climate change and the unthinkable (2016), Ghosh chided environmental ‘discourse’ for its general Eurocentrism and its specific neglect of Asia. By departing from, and regularly returning to, seventeenth-century Maluku, The Nutmeg’s Curse extends this thread while also vehemently affirming that present-day phenomena are and will remain incomprehensible in the absence of a specific form of historical consciousness. A deep sense for planetary ‘entanglements’, explains Ghosh, offers us an alternative to the concerningly commonplace idea that contemporary experience is always ‘utterly novel’ and can therefore never be meaningfully situated in relation to the past. As importantly, an entangled sensibility points beyond the abstractions, provincialisms, and false divisions of such ‘modern, scholarly histories’ that mistake entities like nutmegs or volcanoes for ‘inert’ materials with ‘no world- or history-making powers’ of their own.

Failures and refusals to acknowledge non-human ‘agency and voice’ are, for Ghosh, characteristic of nothing so much as a ‘settler’ worldview. While by no means the first writer to observe this connection, Ghosh is nonetheless at his most original when he rejigs our understanding of its historical development. On his account, a ‘mechanistic’ Western metaphysic did not body itself forth magically out of the minds of such European luminaries as René Descartes and Francis Bacon to render the Earth and most of its peoples ‘mute resources’. Modern thought, Ghosh argues, emerged from the physical violence meted out by imperialists and colonists upon Indigenous peoples and landscapes, not the other way around. As a global and globalising structure, empire also effected the ‘astonishing continuities’ that link disparate places and peoples and that perversely enable planetary thought.

This compelling interpretative line leads Ghosh into some significant disagreements with other influential writers and schools of thought. Primary among the latter is what he calls ‘mainstream Marxist theory’, a framework Ghosh sees as overstating the causal force of ‘economic factors’, especially capitalism, in the course of planetary history. The implication here is not that economics doesn’t matter or that capitalism isn’t a prominent and devastating aspect of the ‘modern gaze’. Ghosh’s point, in this as in many things, has to do with priority, or what we might call, with stories in mind, plot. ‘Capitalism,’ we read, was a consequence – a ‘secondary effect’ – of the ‘military and geopolitical dominance of the Western empires’. An account of, for instance, climate change that excludes imperial from economic histories risks reproducing a very settler-colonial sort of narrative amnesia.

Ghosh’s claims respecting the world-changing – literally ‘terraforming’ – impact of Western imperialism (and above all settler-colonialism) emerge in dialogue with a diverse and far-flung group of indigenous scholars and activists, including Nick Estes (Lower Brule Sioux) and Davi Kopenawa (Yanomami) among others. What Indigenous knowledges and practices hold in common, Ghosh writes, are not only historical experiences of the violences of European colonisation and its ongoing ‘processes’ and ‘planetary forces’ but an understanding of the inalienable ‘vitality’ of the Earth and everything it hosts. Conversely, such understanding tends to elude the inheritors of empire, whom Ghosh represents as rootless, ‘unhinged’, and quite possibly ill. Dreams of terraforming Mars and other planets are, by these lights, expressive primarily of a ‘yearning to repeat an ancestral experience of colonizing and subjugating not just other humans, but also planetary environments’.

If this grotesque feedback loop has an escape chute, it is via what Ghosh calls a ‘vitalist politics’ centrally informed by social justice. Fundamentally ‘anti-mechanistic’ and anti-scientistic, such a politics becomes especially legible, from Ghosh’s perspective, in the work of Native American thinkers like Winona LaDuke (Anishinaabekwe, Ojibwe) as well as in the writing of such Black radical theorists as the late Cedric Robinson. This idea of vitalism also owes significant conceptual and rhetorical debts to the environmental humanities, that large and growing matrix of researchers, artists, and activists committed to other-

than-human liveliness, multispecies relations, and so forth. No theory of agency, Ghosh urges, will hold water that does not accord ultimate generative power to ‘the landscape itself’.

‘Gaia’ is the name Ghosh ultimately adopts for a planet rightly recognised as ‘a living, vital entity in which many kinds of beings tell stories’. The matter of actually hearing, translating, and writing those stories is, as Ghosh would presumably admit, a complex one, attended as it is by knotty narrative concerns. How to strike a balance between figuring imperialism as history’s driver and crediting landscapes (and climates) with formative influence? Can non-Indigenous persons ever really arrive, through ‘empathy’, at a sense for volcanic agency and nutmeggy voice? Ghosh’s ambitious and learned book is not always tidy, but it is frequently electrifying, and our stories will be better for its energies.

Comments powered by CComment