- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Environmental Studies

- Review Article: Yes

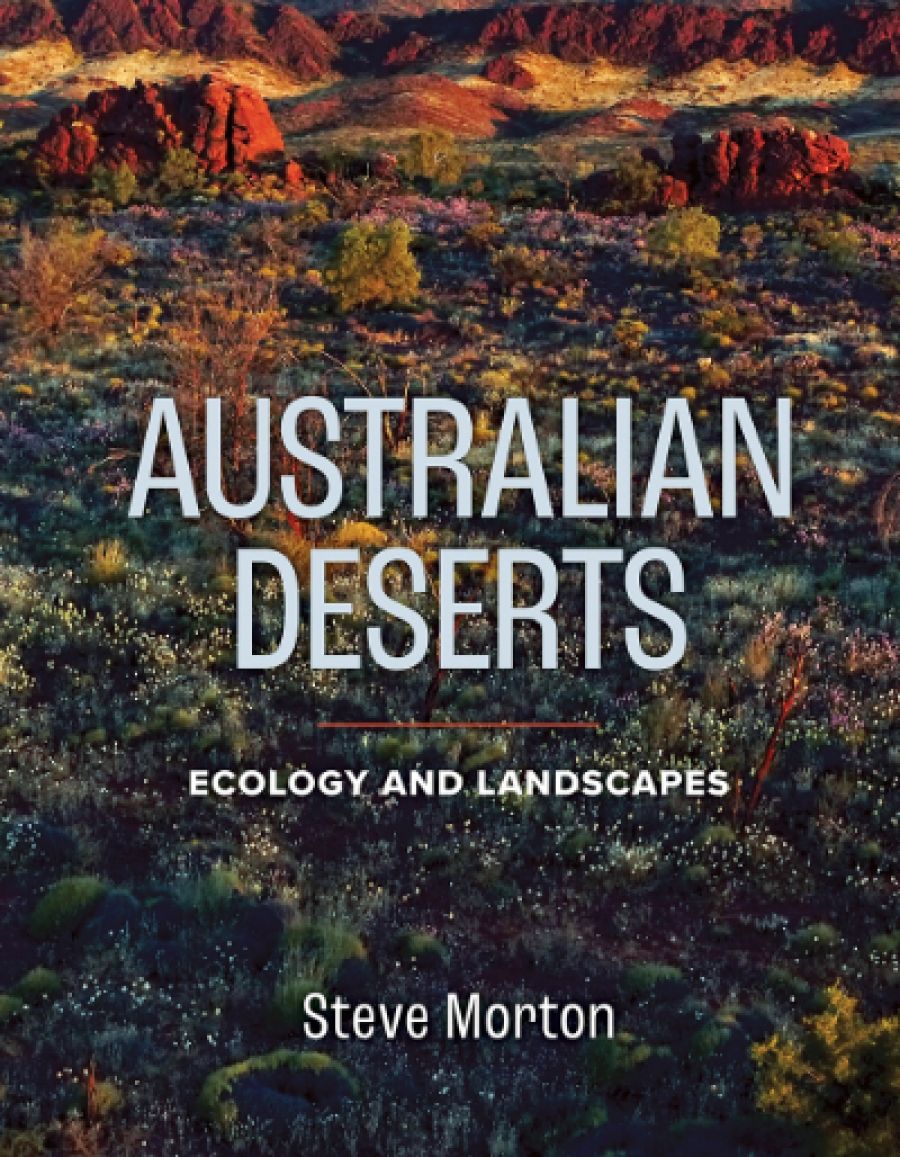

- Article Title: Beyond wind-tortured dunes

- Article Subtitle: The unique wilderness of Australian deserts

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Ecologist Steve Morton’s new book opens with a telling anecdote: as a young scientist in Alice Springs, he often advised visiting film crews about promising locations for their nature documentaries. When one group returned after a week in the desert, they reported back on a single hitch in an otherwise successful trip – a lack of wind-blown sand dunes. To fix this problem they cleared spinifex off a dune, creating a large expanse of bare sand, the illusion enhanced by accommodating morning winds.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Saskia Beudel reviews 'Australian Deserts: Ecology and landscapes' by Steve Morton

- Book 1 Title: Australian Deserts

- Book 1 Subtitle: Ecology and landscapes

- Book 1 Biblio: CSIRO Publishing, $59.99 pb, 304 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/yRv2ay

Iconic deserts such as shifting Saharan sands, cracked playas, or cacti-studded landscapes are persistent in the popular imagination. They are quite different, though, from Australian deserts. A ‘motivation to describe the place on its own merits lies behind my book’, writes Morton. Curiously, this endeavour has a long history.

In 1936, zoologist H.H. Finlayson noted in The Red Centre that ‘the popular idea of a desert is very different from the scientific one, and usually takes the form of a wind-tortured Sahara of drifting sand’. Finlayson contributed to a cultural shift towards appreciating rather than vilifying Australian deserts, suggests historian Libby Robin in How a Continent Created a Nation (2007). In the first half of the twentieth century, other scientists reported back on desert journeys (not always admiringly) in books aimed at general audiences. Morton’s Australian Deserts makes major contributions to this lineage. At the same time, it is quite different from its precursors.

Instead of being based upon a particular journey (or journeys) to the desert, Morton synthesises and distils decades of scientific research, both his own and other scientists’, along with first-hand experience gained from long familiarity with desert environments (he lives in Alice Springs). He acknowledges, too, an ‘abundance of traditional ecological knowledge’ developed over thousands of years by First Nations people in desert regions. Weighted towards accessible science writing, the book weaves threads of personal narrative throughout. These provide vivid insights into the author’s fascination with his subject. Morton refers to the ecologist’s constant process of double vision: to understand the ground at your feet ‘while extrapolating that understanding to … the far distance’. Balancing comprehension of the local and the general – from one square kilometre to five million more – constitutes both the challenge and the ‘delight’ of his career. Morton shares this double vision with his readers.

The book reveals, as it promises, just why Australian deserts are so unlike their northern hemisphere counterparts. The nub of it comes down to two foundational characteristics: unpredictable rainfall, with long dry periods and occasional deluges the norm; and ancient, weathered, infertile soils. Australian deserts may have higher average rainfall than others, but intervals between heavy falls can last months to years. This is not due to ‘capriciousness’ (as even a sympathetic Finlayson put it), but to interactions between atmospheric pressure and sea-surface temperatures, understood better now than ever before, due to advances in climate science.

Unlike other continents, Australia has undergone little ‘geological rebuilding’ (volcanic eruptions, mountain uprisings) over the past 200 million years. Soils have been eroded and sorted by wind and water into pronounced spatial patterns, each with its own texture, moisture retention characteristics, and chemistry. Different soil types attract their own vegetation (arid woodlands, mulga, saltbush, spinifex, grasslands) reliant on those exact conditions, creating a mosaic-like, shifting, ‘continuum of landscapes’, as Morton and Mark Stafford Smith put it in a landmark article ‘A Framework for the Ecology of Arid Australia’ (1990). In Australian deserts, nitrogen and phosphorous, so vital to plant production, exist in unusually low quantities. These factors, along with fire, cascade through and shape life in this environment. One result is that most regions bearing the name ‘desert’ – several distinctive deserts make up the larger arid zone – are abundantly vegetated, which seems counterintuitive.

Morton’s command of his material is compelling. Throughout, he juggles on-the-ground instances of life adapted to desert conditions (such as the startling fire beetle furiously laying eggs beneath smouldering bark, or ephemeral plants depositing 15,000 seeds per square metre of topsoil where they wait for erratic rainfall) with propositions about larger forces at work. A significant example of the latter is a ‘flood’ of sugar-rich foods produced by perennial (long-lived) plants while their roots continually search for scarce nutrients. This distinctive feature of Australian desert plants has a profound effect on animal life, resulting, among other things, in a desert ‘reigned by ants’ – 7,500 species, far exceeding other deserts.

The book is so rich with wondrous details that readers will likely develop their own catalogues. Morton has a gift for bringing to life what he calls the ‘more patient and less dramatic lifestyles’ of species that endure dry times. ‘Boom and bust’ strategies are far better known (encapsulated by the image of flocks of pelicans converging on Kati Thanda–Lake Eyre in flood, breeding and feasting on fish, until waters dry and the last chicks perish, their ‘feathery carcasses scattered across saline flats’). Australian Deserts reveals remarkable processes of persistence and of ‘quiescence’ (inactivity).

A favourite image, for this reader, is that of the desert oak, which grows on deep, porous, apparently waterless sands. The species is adapted to such specific forms of underground water – saturated sediment ‘pooled in depressions in the skin’ of impervious rock layers – its groves become a ‘surface “map” of the scattered accumulations’ below. When Morton and Stafford Smith formed their ‘Framework’ in 1990, later revised with a larger team of authors in 2011, they acknowledged that little was known of such underground processes. Australian Deserts adds a wealth of knowledge to this domain. (Fungi and bacteria attach to root systems and assist with mineralising the nitrogen and phosphorous that are in such short supply; moth larvae dwell inside cool, moisture-filled roots, safe from ravages of heat and drought; termites ‘engineer’ the desert, cycling nutrients through vast earth works; and on an even broader scale, networks of paleodrainage systems lie beneath much of the inland, shaping life above. The list goes on.)

With its breadth and depth of ecological knowledge, enlivened by personal observation, Australian Deserts surely belongs among classics such as Finlayson’s The Red Centre. Fortuitously, Australia has been endowed with ‘one of the world’s last great wild places’ – because the desert has repulsed multiple efforts at economic gain. In turn, Steve Morton gifts his deep understanding of these complex and sometimes confounding places, helping his readers to see, comprehend, and appreciate them in new ways.

Comments powered by CComment