- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Surviving the charnel house

- Article Subtitle: The end of the painter–Minotaur

- Online Only: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Sir John Richardson published the first volume of his monumental A Life of Picasso: The prodigy, 1881–1906, in 1991. The second volume, The painter of modern life, 1907–1917 illuminating the Cubist years, followed in 1996. The next volume, The triumphant years, 1917–1932, appeared eleven years later and gave rise to speculation as to how Richardson, then seventy-three, could complete his ambitious task with nearly thirty years of prodigious production on the artist’s part still to be covered. Now we have the fourth and final volume, The minotaur years, published posthumously – Richardson died in 2019 – with a lot of assistance. It’s the shortest, least compelling volume of the series.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

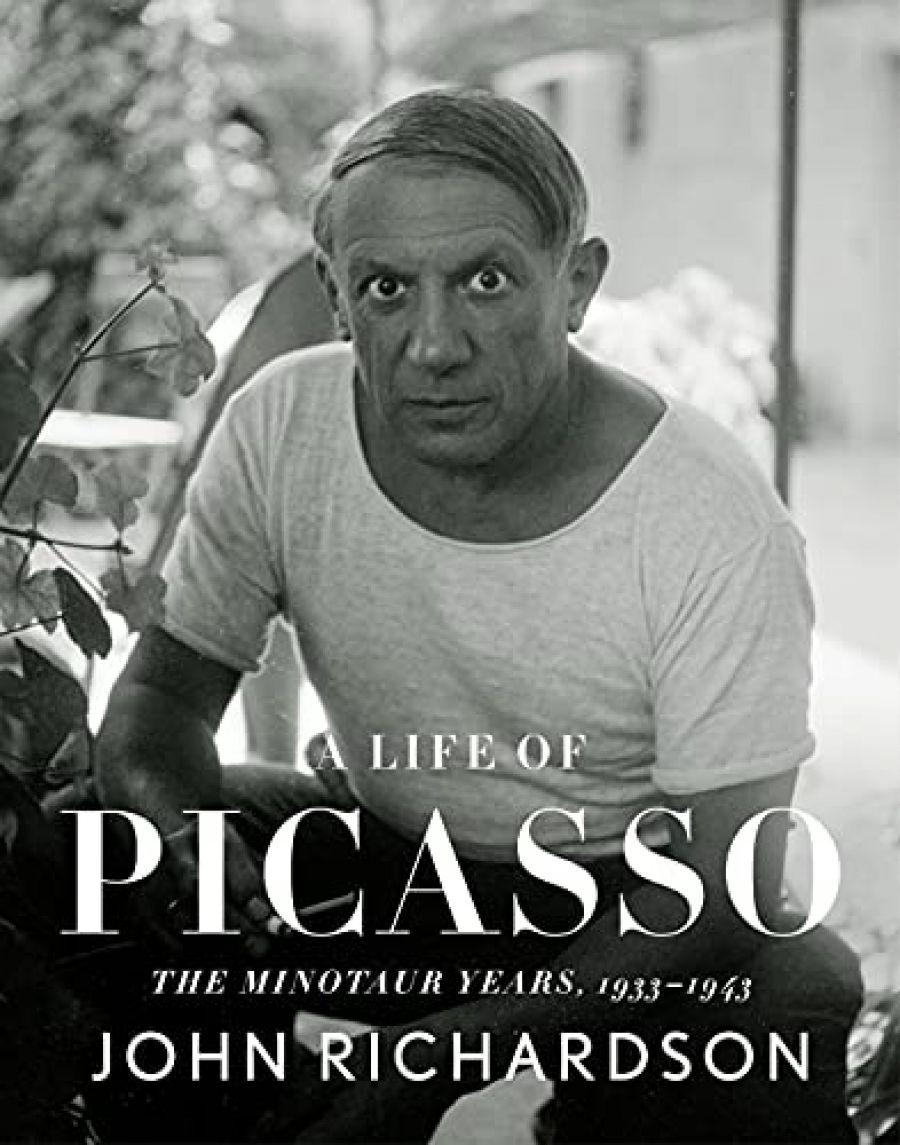

- Article Hero Image Caption: Pablo Picasso (photograph via Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Pablo Picasso (photograph via Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Patrick McCaughey reviews ‘A Life of Picasso: The minotaur years, 1933–1943’ by John Richardson

- Book 1 Title: A Life of Picasso

- Book 1 Subtitle: The minotaur years, 1933–1943

- Book 1 Biblio: Jonathan Cape, $75 hb, 308 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/DVmqAy

That is partially explained by our familiarity with Picasso’s life and work over this decade. The intelligent and gifted, difficult and querulous, Dora Maar replaces the blonde, beautiful, and pneumatic Marie-Thérèse Walter who gave birth to a daughter, Maya, in 1935. The shadow of the Spanish Civil War hung over Picasso with the spectacular outcome in Guernica, painted in twenty-five days in May 1937, all 26’ by 11’ of it, shown to muted acclaim in the Spanish Pavilion at the World’s Fair in Paris. Richardson is icily concise and clear about what happened. Goering intended the destruction of the undefended Basque city by the Luftwaffe as a birthday present for Hitler. ‘Three hours of coordinated air strikes levelled the city and killed over 1500 civilians.’

There are, however, a baker’s dozen of books on Guernica and its plight, making it hard to add much within the confines of a discursive biography. We also know quite a lot about Picasso’s war time in occupied Paris, largely due to San Francisco’s major exhibition on the theme (1998–99). Picasso behaved in an exemplary way. Keeping to himself and his close circle of friends, as a good anti-fascist, he never fell for the blandishments of the occupiers as Jean Cocteau did and totally unlike André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck, who went on a state-sponsored tour of Germany in 1941. Richardson quotes Henri Matisse’s judicious summary of Picasso in Nazi-occupied Paris: ‘He works, he doesn’t want to sell and he makes no demands. He still has the human dignity that his colleagues have abandoned to an unbelievable degree.’ Paris, it must be remembered, had a ‘hot’ art market during World War II where wealthy Germans and collaborating French could shop.

Picasso’s grim wartime work of still lifes, often dwelling on shortages of food and power and taut and tense portraits of Dora Maar, came to a climax in two entirely different masterpieces. In 1943 Picasso contrived to get his full-size Man with a Lamb cast in bronze. The awkwardness of this composition as the lamb struggles in the man’s grasp serves the ambiguity of the piece as a whole: is the lamb being offered as a sacrifice or is it being rescued? The tension absolves the sculpture of all sentimentality and fixes on the struggle to survive.

The other work, The Charnel House (1945–46), alas goes unrecognised in the present volume. Picasso painted it in response to the first images he saw via the American photographer Lee Miller of the murdered Jews of Europe. He deploys once again the grisaille palette of Guernica and the same linear Cubist drawing style. The prone victims gasp for air – one with tied hands reaches vainly upwards. The painting falls outside Richardson’s terminus of 1943, the year that Picasso meets Françoise Gilot, Dora Maar’s less temperamental, more independently minded successor. That Richardson should choose for his termination point the transition from one mistress to another rather than the end of World War II gives some aid and comfort to his critics, most notably T.J. Clark, who accuse him of reducing his mighty subject to gossip. Although there is a fair sprinkling of paragraphs that begin ‘Picasso once said to me …’, there is only one egregious example of gossip triumphing over biographical enquiry when Richardson sorts out who was sleeping with whom in a large party summering with Picasso at the Hotel Vast Horizon in Mougins in 1938. Who cares?

The biographical approach to Picasso has frequently been criticised, and Richardson has taken more lumps than anyone on this account. But there is no major artist in Western Art who paints, draws, etches, sculpts his life, his daily preoccupations, as well as his deeper fears and instincts, so compulsively as Picasso. The familiar divisions between art and life dissolve.

Richardson’s biography is not all beer and skittles, not all gossip and shenanigans. He traces a persistent dread in Picasso’s art and life over the decade covered by this final volume. Picasso was deeply frustrated over the lingering bonds of his disastrous marriage to the ballerina Olga Khokhlova – an unlovely combination of termagant and hypochondriac. He investigated the possibility of a divorce in Spain under the more liberal laws of the Republic. He shuddered at the prospect of a French divorce, which would have resulted in their property, including all of his accumulated work, being equally divided between them. Richardson, no fan of Olga’s, does point out fair-mindedly that she showed no interest in taking his art from him. Picasso would eventually win a judicial legal separation in 1940.

The Spanish situation was a constant source of concern and anxiety. Picasso’s mother and sister were still living in Barcelona during the Civil War. He was a generous donor to Republican causes, from milk for children in Spain to funds for refugees. After the war, while Franco’s secret agents swept through France looking for prominent anti-Franco survivors to extradite and punish in Spanish courts, Picasso vainly tried to obtain French citizenship, denied to him (incredibly) on low-level intelligence that he had been heard promising his entire collection to the Soviet Union. It did not deter two Gestapo goons from visiting his wartime studio on the Rue des Grands Augustins and roughing up the place, kicking in canvases and creating general mayhem.

Deeper than all these vexations and imagined threats was Picasso’s descent into the darkness of seeing himself as the Minotaur – half man, half bull. The violent lusts of the Minotaur caused deep anxiety. Then Picasso blinded the Minotaur; Picasso knew no deeper fear than blindness.

All this led towards a breakdown in 1935 when he stopped painting for the best part of a year and summoned his old Barcelona friend Jaime Sabartés to Paris to act as his secretary and general factotum, somebody he could talk to in Catalan late into the night.

During his sabbatical from painting, Picasso turned to writing poetry, scads of it, enraging Gertrude Stein. Picasso was nature’s Ern Malley, scattering words like flecks from a brush:

The slender sojourn of the secret price of pain simmers on the low fire of memory where the onion plays the star of the hand detaches itself from its lines having read and re-read the past but at the crack of the riding whip straight in the eyes.

Aren’t you glad he recovered and returned to painting?

Comments powered by CComment