- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Features

- Custom Article Title: Chris Wallace-Crabbe reviews 'Collected Poems: Francis Webb' edited by Toby Davidson

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The deeply troubled Francis Webb, a magician with language, is still one of the two or three most remarkable poets Australia has produced, if nation-states can be said to produce creative artists. His life proved dark and painful, wherever he was located, but he worshipped language, in parallel with his worship of the Christian trinity ...

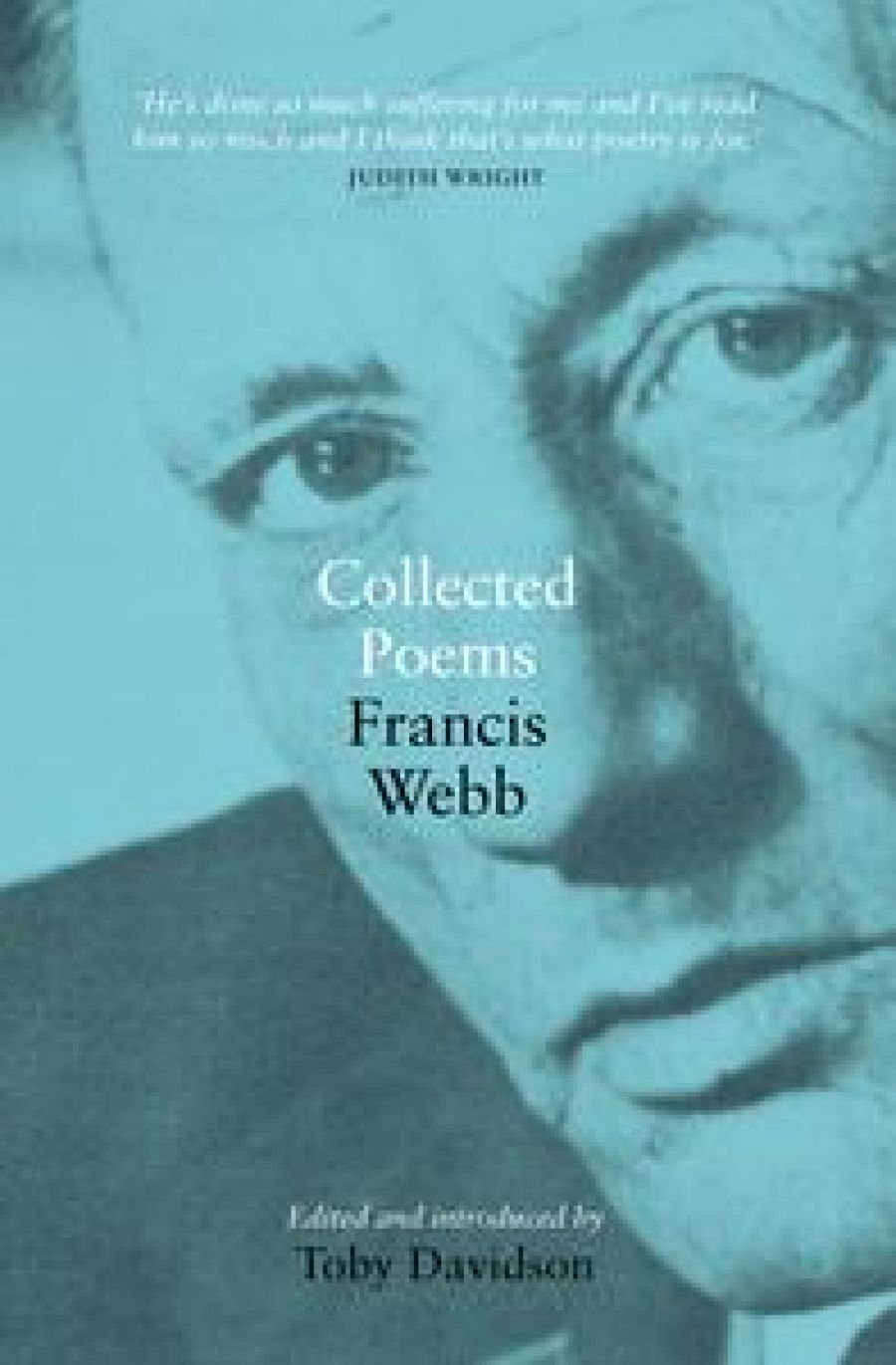

- Book 1 Title: Collected Poems

- Book 1 Subtitle: Francis Webb

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing, $32.95 pb, 480 pp

My first acquaintance with Webb’s verse was when that garrulous raconteur Frank Clune presented my father with a copy of A Drum for Ben Boyd, a 1948 sequence of historical episodes, with lairy, stylish illustrations by Norman Lindsay. The 1940s and 1950s were a great period for explorer poems, and this volume played its part: it even led to my family visiting tatterdemalion Boydtown on the New South Wales south coast.

A few years later I was working in the city and, as well as haunting Cheshire’s bookshop, I kept dropping into the narrow Angus & Robertson shop at the bottom of Elizabeth Street. One day, I spotted a copy of Webb’s Birthday, a shoddily produced little book, dull grey and possibly back-stapled. I paid out my seven-and-six – or was it twelve-and-six? – and began to explore the poet’s exciting densities. Here, I felt, was a new way forward for poetry in this country, a voice more modern than Kenneth Slessor’s.

‘Port Phillip Night’ and ‘Laid Off’ were intensely orchestrated, doing for Melbourne what Hart Crane had so thrillingly done for Manhattan in the 1920s; and Crane’s example had certainly influenced the Australian poet. Admittedly, I skated over some of Webb’s religious tropes and structures, but the poetry was frequently thrilling and a creative inspiration to me. Only the eponymous piece, an odd radio play based on Hitler’s birthday and death in the bunker, felt willed or laboured.

I was not yet to know how deeply Webb’s psyche fed on, and was threatened by, excess. Personally, he was a mystery, although known to Vincent Buckley from his short time in Melbourne during the early 1950s; but many of us were excited by the Hopkinsian element in the poetry. It came to us gradually, seductively.

For many readers – even if, whipped along by Douglas Stewart, the Lindsayite literary editor of the Bulletin, they were already aware of the poetry of exploration – a first exposure to Webb’s lyric art was through ‘For My Grandfather’. This was his only poem in the 1958 Penguin Book of Australian Verse, and an appended bio-critical note makes it plain that the editors were ill at ease with his modernism: they went so far as to set a complaint about his obscurity against a London reviewer’s enthusiasm for Webb’s muscularity. They sat on the fence.

‘For My Grandfather’ is a beautifully evocative poem, saturated with the sea. The dear dead man is merged with a wreck, so that

against the bony mast

Work in like skin the frayed and slack-

ened sails.

In the green lull where ribs and keel

lie wrecked,

Wrapped in the sodden, enigmatic sand,

Things that ache sunward, seaward

with him locked

Tug at the rigging of the dead ship-lover’s

hand.

Webb worked poetically against separation, against Cartesian dualism or materialist reduction. His impacted syntax strove to bring together the human and the natural, but also body and spirit. His poems were metaphorically driven, finding incarnation in everything around him. ‘Dawn Wind on the Islands’ and ‘Morgan’s Country’ are among the finest examples of such intensity, the latter also a bushranger crisis poem.

All poetry, all writing, wears the badge of its time, the particular markings of its age or clan. We glimpse this at the end of Webb’s elegy, where he writes ‘Rather than time upon my wrist I wear / The dial, the four quarters, of your death.’ This kind of high-toned surrealism smacks of the 1940s, and especially of the overseas ‘Apocalyptics’: George Barker, Henry Treece, and the early Dylan Thomas. Buckley had written about those poets with some misgivings, but was a steadfast supporter – and anthologist – of Webb’s poetry, finding in it that combined religious belief and subtle verbal richness that could be for him at the very core of modern writing.

Webb had served in the air force, which may have lent authority to his expressive landscapes from above, as in ‘Dawn Wind on the Islands’ and ‘The Gunner’, from the same period. It might be worth reflecting that the poet-friend who played a large part in bringing Webb back to Australia in 1960, David Campbell, was also an ex-airman, though a very different responder to landscape; a pastoral lyrist, in effect. Without a doubt, there were ways in which air force service informed Webb’s responsive imagination, even though he saw no active combat.

But at every stage much of his strength lay in the expressive activation of landscape. Thus, in the late ‘Wild Honey’, we encounter this agitation of autumn:

Saboteur autumn has riddled the

pampered folds

Of the sun; gum and willow whisper

seditious things;

Servile leaves now kick and toss in

revolution,

Wave bunting, die in operatic reds

and golds ...

The English poet Tony Harrison once noted that poetry ‘draws attention to its own physicality’. Webb always makes language tangible, physical, charged with agency, not only by wrestling with hyperactive verbs, but also by employing a rhythmical fullness similar to that of Yeats, particularly at the end of stanzas. Understatement was alien to his poetry, anthropomorphism rampant.

To take another example, the reader, reading a ballerina poem, might well pause, frowning, over how ‘The world shrugs tipsily, well ballasted / with shouted pint on pint of silent dreaming’.

Such verbal expressionism could always run the risk of overdoing it, in the interest of emotive power. And I think here of a local Poundean’s attack on Buckley, long ago in Meanjin, for that poet’s similar catachresis, which was a nice baroque noun to get into the modern critical vocabulary. The application of extreme torsion to the language was one possible response to a time of crisis, even if it led to comic mockery in the scarecrow figure of ‘Ern Malley’. After all, these were the years soon after World War II.

In other respects, Webb’s poetry was closer to an Australian norm, especially in the exploration suites dealing with Leichhardt, Jacques Cartier, and Eyre. History was still being read like that, in the mid-twentieth century. And the form of these suites had much in common with the postwar verse play, which flourished in the wake of T.S. Eliot and Christopher Fry. Strange as it seems now, we were set a whole book of verse plays to study in secondary school. Moreover, Webb did write two verse plays, which are included here, both of them embroiled with violence, one on Hitler’s death and the other on electric shock treatment. His personal experience was deeply troubled. Toby Davidson, editor of the Collected Poems, has observed that ‘Webb’s life-long empathy for the vulnerable, marginalized and oppressed is continually reaffirmed from “The Hulks at Noumea” to “Ward Two” and it is indistinguishable from his Catholicism.’

One complexity in our understanding of this poetry, as with certain other major writers, is learning how to balance the writer’s mental instability with his creative vividness. Yes, Webb was enclosed in mental hospitals for much of his adult life, yet the one consciousness could produce that beautifully lucid lyric ‘Five Days Old’ as well as the denser poems of division. Imaginative power walks all too often on a knife-edge.

As the authors of Intimate Horizons, a recent book on ‘the post-colonial sacred’, have suggested,

Webb is in some respects more deeply religious than any other Australian writer. Religious but culturally intuitive, he is torn by the conflict between the sacred as the luminous goal of spiritual contemplation, and the sacred as a feature of the everyday ...

They also stress how deeply immersed the poet had been in canonical Catholic writers: not only in his obvious linguistic precursor, Hopkins, but also in the theologians.

Plainly, after the secular Ben Boyd drumming, Webb’s exploration sequences are large metaphors for the life-quest of the Christian soul. With Leichhardt and Eyre, he can displace his own conflicts largely onto the exploration of our country, onto versions of the Christian hero. His poetic structures had a great need for protagonists, and, desert explorers aside, these ranged all the way from Stendhal to Mahler, to St Maria Goretti at the very end. Female saints emerged in those last few poems, Webb’s panorama of action having been very masculine indeed.

I met Webb at last during his time in a Victorian mental hospital, when he had a great deal of support from the doctor–poet Kel Semmens. They turned up to a couple of readings I gave at La Trobe University. I was struck by how calm, grey, and courteous Webb was; he called me ‘Sir’ when he asked questions. This encounter felt important because, by then, I knew how much time he had spent in such hospitals, in England and Australia.

The ‘Ward Two’ suite, written in 1960, is somehow an important focus, both for its compassion and for its straining to understand fellow sufferers. The homosexual in whom Webb finds a sacredness, a presence of Christ:

And now he is here. We had him con-

veyed to this place

Because our pale glass faces contorted

in hate or merriment

Left only sin as flesh, the concrete, the

demanded.

The diction has become plainer here, even as Webb struggles to articulate what the homosexual man’s life might be like. And the ‘pale glass faces’ function as a chorus through this section. We can lament, too, that anthropomorphic drama is here much abated without access to landscape, to what Wordsworth called ‘natural objects’.

Early or late, Webb’s abiding sense of Christ incarnate in our world was strongest when he could capture or recreate it in the natural environment. It is a true environment of interaction in which the poet can ‘give his body to the gesticulating / Green grass without forethought’. In such a frail moment of harmonious interaction, ‘Bides colour, and of the draughtsman, the Beginning’.

To judge from the poems, Webb’s troubled soul always sought harmony in which might be located a glimpse of transcendence, a momentary phrasing of peace. It is from this tough quest that the richness of his work arises. Collected Poems is a book of great significance, bringing Francis Webb the poet back clearly before us.

CONTENTS: MAY 2011

Comments powered by CComment