- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Features

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In January this year the New York Times ran a controversial review article titled ‘The Problem with Memoirs’, in which staffer Neil Genzlinger praised ‘the lost art of shutting up’. He heaped scorn on ‘our current age of oversharing’ and on the accompanying glut of memoirs on every imaginable aspect of human experience. But he reserved particular scorn for what he identified as the latest trendy topic: ‘books by parents, siblings and teachers of people with autism.’ He advised, ‘If you’re jumping on a bandwagon, make sure you have better credentials than the people already on it.’

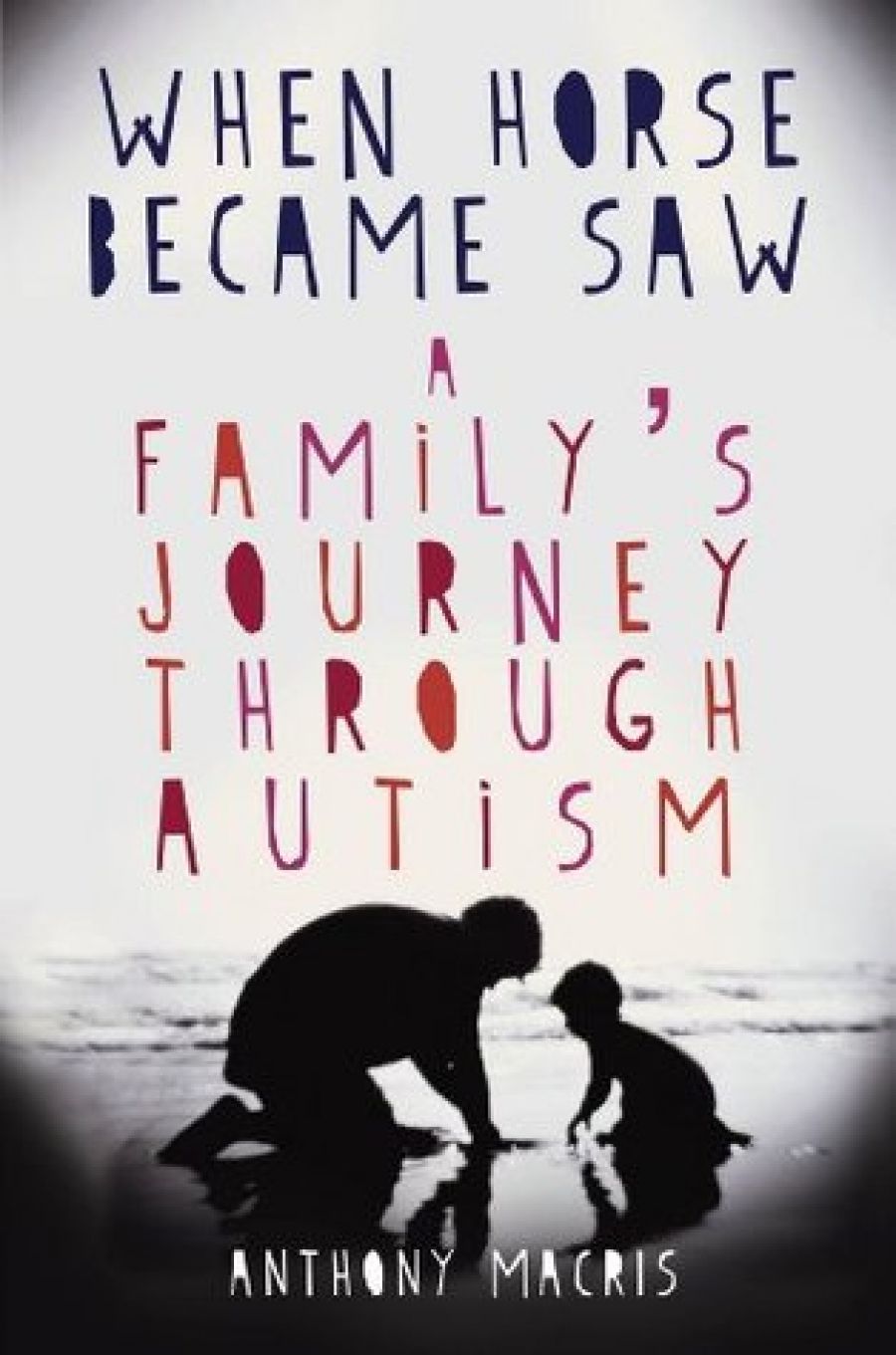

- Book 1 Title: When Horse Became Saw

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Family’s Journey through Autism

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $32.95 pb, 307 pp

Having read many autism memoirs, I would argue that Anthony Macris does have superior credentials. First and foremost, he is a professional writer; a novelist and critic. From the opening pages it is clear that the reader is in the hands of an accomplished storyteller; that Macris is not only taking us inside his experience, but that he has thought hard and long about how best to communicate it. Some autism memoirs are, ironically, like a conversation with a person with high-functioning autism (Asperger’s Syndrome). They successfully impart information, much of it useful, but are less successful at filtering and sorting that information with their conversational partner – the reader – in mind. As a result, they don’t have much appeal beyond the narrow audience of other people in their situation. Macris employs his novelist’s skill in selecting and juxtaposing telling fragments of his experience so that he not only tells the reader the facts of his experience, but invites them to understand how it might feel to live it.

When Horse Became Saw opens with a tableau of Macris and his wife, Kathy, preparing to receive a visitor who will talk to them about putting a financial plan in place to provide for then-toddler Alex’s future university education. They are hoping to shield Alex from the demands and restrictions of a government obsessed with ‘self-reliance’. ‘We had brought Alex into the world, now we had to make sure he was given every chance.’ This snapshot of early hope and promise provides an aching contrast with the years of difficulty that follow, as Alex descends into an autistic regression, losing most of his newly acquired language and his ability to communicate with and comprehend the world around him.

Macris describes in evocative detail how the symptoms that were to lead to a diagnosis of autism gradually unfolded: confusion at a simple game previously mastered, being unable (not simply unwilling) to drink out of a bottle different from his habitual one, a habit of walking on his toes, an unusually high pain threshold, and, finally, repeated manic laughter, an inability to sleep, compulsive running and spinning (‘stimming’), and loss of words. More than that, Macris brilliantly captures the experience of watching his son ‘drift into some strange, terrifying world [where] we could not follow’, blending imagination, observation, and science. His intuitive descriptions are informed by a thoroughly researched understanding of what autism means on a neurological level, married with intricate observations of how this plays out. ‘It was like being in a science fiction film. The world seemed normal but there was an alien force at work, capable of penetrating an individual’s nervous system, and rewiring it, leaving them physically unchanged yet altered beyond recognition.’

Another element that distinguishes this memoir is its political charge. Macris is understandably damning of the meagre and disastrously ill-timed services offered by the government (including standard six-month waiting lists at every stage of assessment and treatment), and appalled that the health workers he comes into contact with agree that what the system offers is ‘unacceptable’. ‘The shock of what was happening to Alex was one thing,’ he reflects, ‘but the government’s inadequate response was another ... On the one hand they urged early intervention, but on the other didn’t seem to have the will to provide it.’

Eventually, Macris and his wife, Kathy, after exhaustive investigation, turn to a time-intensive, shockingly expensive (minimum $30,000 per year) private treatment method, Applied Behavioural Analysis, which requires a parent to take on the bulk of the therapy work. Reflecting on the Howard government’s much-lauded budget surplus, Macris says, ‘These were some of the ways the savings were made. By doing next to nothing for children like Alex.’ This memoir serves as an appalling – and starkly effective – indictment of a welfare state ‘stripped to the bone’, a society that makes no provisions for its less fortunate members, with tragic results. Macris is sharply aware that he and his family, afflicted as they are, are among the lucky ones. He details the hard work and singular, draining focus (emotional, physical, mental, financial) they employed, over several years, to give their son ‘every chance’. Crucial to their success in re-engaging Alex with the world was not just their emotional fortitude (Macris particularly praises Kathy’s reserves of patience), but also their ability to raise much-needed extra finances and their dogged application of their established vocational skills (in research and teaching) to their son’s plight. Few in their situation would have such reserves to draw on.

Macris decries a key side-effect of the government policy of ‘self-reliance’: parents of autistic children are ‘so busy supporting [their] own child, [they have] no time to get organised and lobby for anyone else’s’. With When Horse Became Saw, he effectively lobbies on behalf of all of Australia’s autistic children. Bravo to this memoir writer for not shutting up.

CONTENTS: MAY 2011

Comments powered by CComment