- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The vampiric supply chain

- Article Subtitle: Amazon’s experiment in literary populism

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

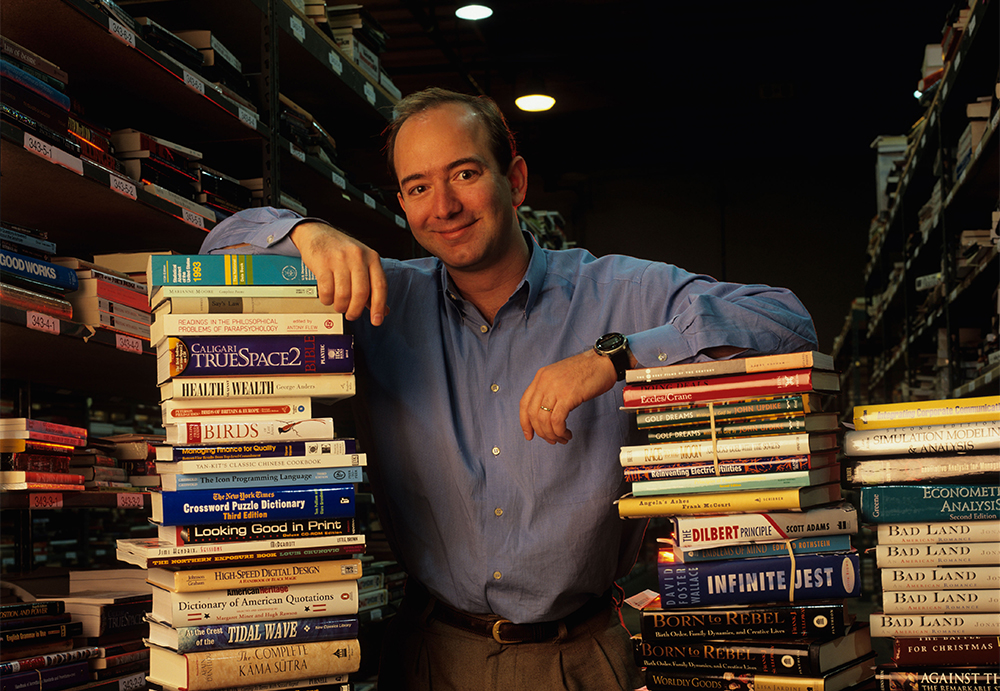

On 21 July 2021, one of the world’s richest men, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, staged a press conference in the small town of Van Horn, Texas, the purpose of which was to boast about his recent ten-minute joy ride into space atop a rocket so comically penis-shaped that one could be forgiven for thinking that the whole exercise was intended as an outrageously expensive joke, albeit one that Mel Brooks would likely have rejected for its lack of subtlety.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Amazon president Jeff Bezos with stacks of books inside huge warehouse in Seattle, 1998 (Worldfoto/Alamy)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Amazon president Jeff Bezos with stacks of books inside huge warehouse in Seattle, 1998 (Worldfoto/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): James Ley reviews 'Everything and Less: The novel in the age of Amazon' by Mark McGurl

- Book 1 Title: Everything and Less

- Book 1 Subtitle: The novel in the age of Amazon

- Book 1 Biblio: Verso, $39.99 hb, 333 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/qnGE2y

The lickspittle, whose name I can’t be bothered finding out, then presented them with commemorative lapel badges, which he pinned with some difficulty to their lumpy suits. There were smiles and hugs all round. In an apparent show of deference to the rustic setting he had chosen for this historic display of crapulence, Bezos had augmented his shiny blue spacesuit with a pair of tan cowboy boots and a grubby stetson, a wardrobe decision bold enough to call into question his judgement on other matters, but which did nothing to disguise the fact that he was basically a chinless geek with a degree in computer science who looked like he was using all of his willpower to prevent himself from jumping up and down on the spot and clapping his hands with glee like a three-year-old at Christmas who has discovered that he gets to have everyone else’s presents too. ‘I want to thank every Amazon employee and every Amazon customer,’ he blathered, ‘because you guys paid for all this!’

I would like to digress briefly at this point to say a big hello to Karl Marx.

Marx’s name does, in fact, crop up several times in Mark McGurl’s Everything and Less: The novel in the age of Amazon, though not, alas, in the service of any kind of rigorous critique of the company’s ruthless monopolistic ambition and disgraceful employment practices. While McGurl acknowledges that Amazon has ‘many detractors’, and while he discusses various ways in which it might be considered an ethically questionable operation, his attitude is tempered by a sneaking admiration. ‘If we could bracket the million troubling implications of its rise,’ he writes, ‘we could easily admit that it is one of the most impressive ventures of our time, equal in its way to the aqueduct system, cathedrals, and moonshots of the past, those triumphs of logistics it distantly resembles.’

One cannot fault the logic. Nothing is more apt to make something seem good than discounting a million things that are bad about it. And McGurl, to be fair, is writing as a literary scholar, not an economist or political scientist. His concern in Everything and Less is not to pass judgement on Amazon, as such, but to consider the objective fact of its market dominance. He admits that his thesis is essentially the same as that of his previous book, The Program Era: Postwar fiction and the rise of creative writing (2009), a widely discussed cultural history of MFA programs in the United States, which argued that the institutional support such programs provided for writers had a decisive effect on the form and evaluation of ‘literary production’. Everything and Less simply shifts the focus from the academic realm to the commercial. McGurl proposes that ‘the rise of Amazon is the most significant novelty in recent literary history, representing an attempt to reforge literary life as an adjunct to online retail’.

Therein lies the central conundrum of Everything and Less. It hardly needs emphasising that Amazon, the self-proclaimed ‘Everything Store’, is in the business of selling things. It doesn’t care about the content or the quality of the books it sells; it just wants to shift as many units as possible. As far as Amazon is concerned, differences between books are of interest only insofar as they reflect consumer preferences. You might want to read Middlemarch or you might want a copy of Space Raptor Butt Invasion – which, thanks to McGurl, I now know is one of a popular series of high-concept pornographic novels by Chuck Tingle that also includes Bigfoot Pirates Haunt My Balls and (I swear I am not making this up) Slammed in the Butt by the Prehistoric Megalodon Shark Amid Accusations of Jumping Over Him. Amazon, the ‘market personified’, will gladly sell you either or both, noting your predilection with a view to selling you similar books in the future.

On these grounds, McGurl argues in his introduction that ‘literary fiction’ should be considered a genre, in the sense that it cannot escape the irresistible taxonomies of Amazon’s algorithm-driven brand of consumer capitalism. So-called ‘literary fiction’, he maintains, is ‘the genre that likes to think of itself as non-generic’, but in reality it is merely ‘one genre among many’.

McGurl presents this assertion as a humbling truth: one in the eye for all those obsolete idealists who cling to the idea that literature might be something more than just another commodity. Its deeper significance lies in its combination of the question-begging and the plainly false. The most charitable thing that can be said about the term ‘literary fiction’ is that it is vague. From a reader’s perspective, as distinct from that of an online retailer, it is meaningless as a generic classification because it says nothing about a work’s formal properties. Is that ‘literary fiction’ like George Eliot or like Clarice Lispector? When Mikhail Bakhtin defined the novel as an anti-genre, he was not suggesting that it was non-generic; he was noting that it has the capacity to incorporate and recombine many different narrative structures and new modes of expression. He was pointing out that the formal properties of a ‘novel’ are not predetermined or fixed. In this sense, the notional opposition of ‘literary’ and ‘genre’ fiction has always been a straw man. All novels have generic properties. That the adjective ‘literary’ has become a lazy way to describe books perceived to be prestigious for whatever reason (or that at least have aspirations in that direction) is a relic of the old, exploded distinction between high and low culture; which is to say, it functions as a qualitative claim for marketing purposes rather than a substantive term.

I take this to be McGurl’s point, at least in part. The levelling logic of consumer capitalism has co-opted whatever lingering cultural prestige literature may once have had. Your fancy ideas about artistic integrity and the life of the mind are of no consequence; in the end, a book is just a product and you are just a customer like everybody else. Should you object that ‘literary life’ is not simply a matter of buying books, but the meaningful labour of writing, publishing, reading, translating, and discussing them, McGurl has the ready response that Amazon has insinuated itself into those activities as well, having devised ingenious ways to cream profits from literary endeavour at every stage. The company’s ambition is no less than to expand its interests to the point where it is a ubiquitous presence, all but synonymous with the capitalist system itself: ‘Echoing a familiar quip to the effect that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism,’ writes McGurl, ‘we could say that ideally, for Bezos, it would be easier to imagine the end of capitalism than the end of Amazon.’

McGurl does not identify the source of this ‘familiar’ line, which has been variously attributed to Fredric Jameson and Slavoj Žižek, but was given currency by Mark Fisher’s Capitalist Realism: Is there no alternative? (2009). Fisher presents the remark less as a ‘quip’ than as an encapsulation of capitalism’s basic confidence trick, which is to perpetuate the illusion of its inevitability. His point is that recognising that we are all implicated in its processes is the first step towards understanding that there is nothing natural or inevitable about a rapacious system that generates outrageous social inequalities and environmental devastation on a global scale so that a billionaire manbaby can play space-cowboys. ‘To reclaim real political agency means first of all accepting our insertion at the level of desire in the remorseless meat-grinder of Capital,’ Fisher argues. ‘What needs to be kept in mind is both that capitalism is a hyper-abstract impersonal structure and that it would be nothing without our co-operation.’

Much of the oddness of Everything and Less can be attributed to McGurl’s acceptance of the idea that we are all implicated in Amazon’s universe of consumerism at the level of desire, without troubling himself to imagine anything beyond the capitalist utopia of the present. ‘The pleasures we seek are already at hand,’ he claims. McGurl attributes Amazon’s success to its unique emphasis on customer satisfaction (as if ‘the customer is always right’ were not retail’s hoariest adage). The company’s strategy, he observes, has been to identify and satisfy our desires as swiftly and as cheaply as possible, hyper-charging its distribution systems with sophisticated computer algorithms and, in its early years, adopting the aggressive business strategy of pursuing rapid growth at the expense of profits until it had achieved a large enough market share to press home its advantage and crush its competitors.

Books were a convenient Trojan horse for Amazon’s ambition to sell anything and everything because they were non-perish-able and easily shippable. McGurl proposes that they came with the additional advantage that they were eminently classifiable, and thus highly legible as desired goods. ‘Amazon is the host of a genre system,’ he argues, ‘conceived as an engine of infinitely infoliating permutations of narrative desire.’ One could argue (recasting his metaphor) that this is confusing the host with the parasite, since the company produces very few products of its own. For McGurl, however, the fascinating thing is the implied metaphysics of consumerism. The insight upon which Amazon is built is that our desires can be identified and satisfied because they are themselves generic.

Everything and Less develops several arguments in support of its thesis that Amazon is redefining the aesthetics of the contemporary novel. Some of them are interesting as provocations; none is ultimately convincing. McGurl’s assumption of Amazon’s commercialised perspective makes him susceptible to the rationalisations that underpin its version of capitalist realism. His book is heavily invested in the notion that the company is, to use the self-flattering terminology of tech entrepreneurs, a ‘disruptor’. He contends that the rise of Amazon compels us to reconceptualise fiction as a ‘service’ and the role of the writer as that of an ‘entrepreneur’ and ‘service provider’. Its innovation has been to offer readers electronic access to vast quantities of cheap fiction via Kindle (one of the few products the company manufactures itself) and writers the opportunity to bypass traditional publishers via its self-publishing platform Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP).

McGurl observes that these developments have empowered ‘indie’ writers to connect with readers directly, without the kinds of institutionalised cultural mediation that once prevailed, and in some cases earn a decent living from their work. He dwells, in particular, on the example of E.L. James’s salacious bestseller Fifty Shades of Grey (2011), which began its life as a piece of online fan fiction based on Stephenie Meyer’s popular Twilight series of vampire novels, and which McGurl reads, cleverly, as an illustrative generic synthesis that owes much of its appeal to the way it redeems the depredations of capitalist exploitation, embodied in the figure of a sadistic ‘alpha billionaire’, through the narrative conventions of the popular romance novel. (Given that Bezos’s fellow entrepreneur Peter Thiel has openly canvassed the idea of prolonging his life with infusions of younger people’s blood, one can’t help but feel that the novel would have been more credible if the author had left the vampirism in.)

Yet commercial success is, inevitably, the exception not the rule. The predictable effect of Amazon’s radical experiment in literary populism has been to flood the market with worthless writing. McGurl records the boggling statistic that in 2018, while traditional publishing houses in the United States were producing new books in their tens of thousands, another 1.6 million works were self-published.

The vastness of this indigestible mass of words is chastening. If nothing else, it might return us to the fundamental question of why we read and write in the first place. Amazon’s answer, and McGurl’s, is that we read to fulfil desires. This is something of a truism. It accords with the individualistic imperatives of consumerism, reinforcing the assumption that novels are sources of entertainment, pleasurable distractions from reality, indulgent if not entirely frivolous. But the fact that novels appeal to our imaginations is also the source of their power. They remind us of the autonomy of our own minds, even as they draw us into the ideas of others, and this makes their influence unpredictable.

Everything and Less acknowledges this in an interesting if unresolved way. One of the conceits that runs through the book is that Amazon is a novelistic enterprise: a realisation of the grand imaginative vision of its founder. McGurl describes the company as the successor to the literary avant garde. He notes the way that American culture regards billionaires as heroic figures, avatars of self-realisation, who overcome obstacles and remake the world after their own designs. He also places considerable emphasis on the fact that Bezos is known to be an admirer of Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel The Remains of the Day (1989), which he encourages all his employees to read.

We cannot know for sure how Bezos interprets Ishiguro’s fiction about a starchy old butler named Stevens. He might understand it as a cautionary tale about becoming stuck in the past, or he might appreciate its meditation on the notions of honour, duty, and loyalty. But what makes the detail intriguing is how oddly it sits with the apparent ethos of the ‘Everything Store’. The Remains of the Day is, among other things, an extended exercise in dramatic irony, in which the reader is able to grasp quite quickly – well before the narrator himself – that Stevens’s belief system is no longer supported by reality. History has moved on and he has not; his determination to cling to his old values, his old ideas about order and propriety, proves to be so strong that he cannot recognise this fact until his world has crumbled to dust. He is the last person to learn the truth about himself. One way of interpreting the novel might be to see it as a fable about the vulnerability of all ideas. That would extend its implications to the contemporary notions of the heroic billionaire and the capitalist as benefactor. What seems indisputable may well seem absurd later. Ideologies are powerful, but they are never unassailable; sometimes they can have a surprisingly short shelf life. Novels, if they are good enough, tend to last a little longer.

Comments powered by CComment