- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Soeharto’s various worlds

- Article Subtitle: A nuanced portrait of President Soeharto

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

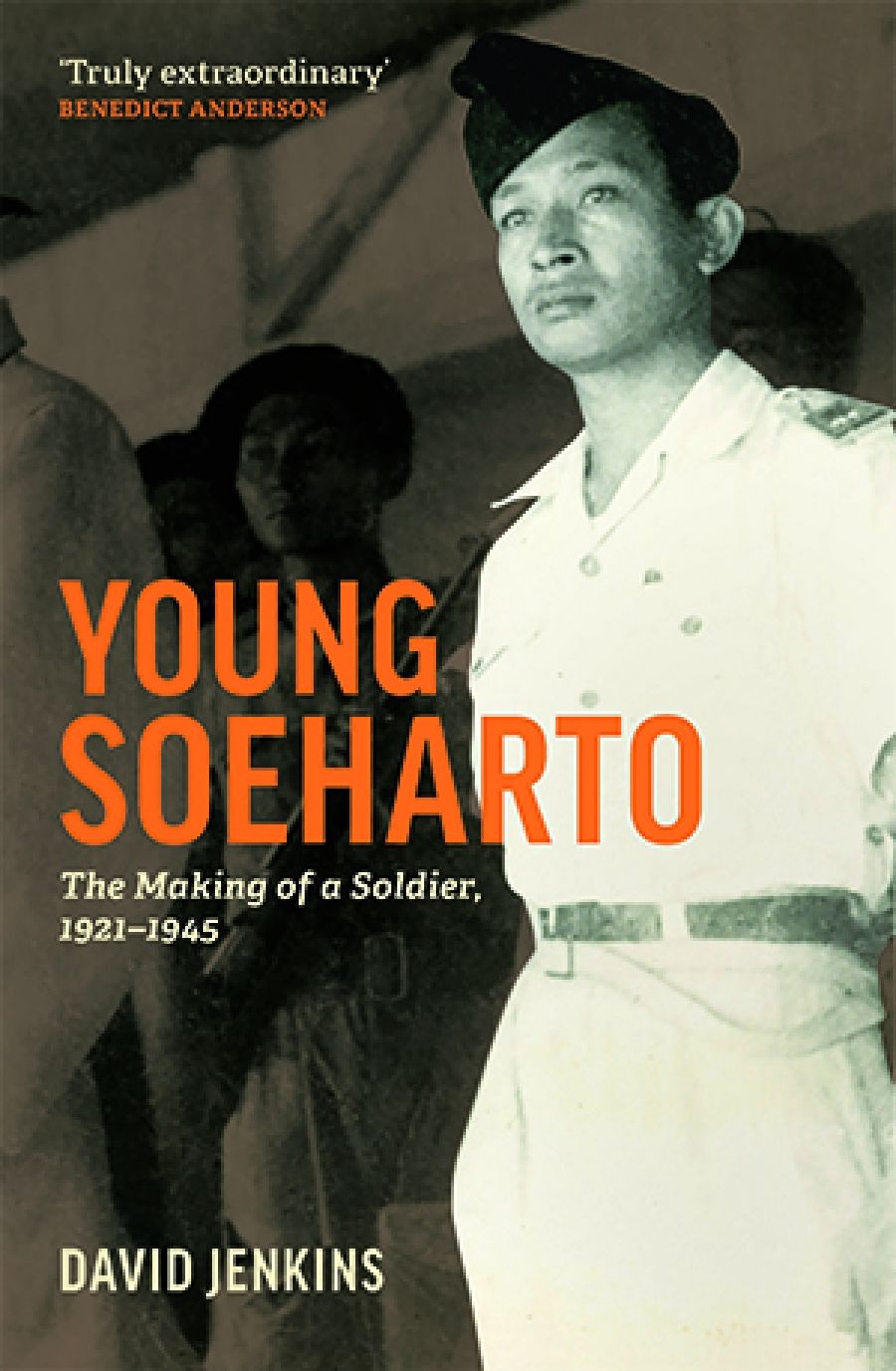

At last we have it – the much-anticipated first volume of the definitive biography of President Soeharto (1921–2008). It is the culminating work in the distinguished career of Australian journalist David Jenkins. This startling volume, covering the years 1921–45, will appeal to the general reader and the Indonesia specialist. It has been described as ‘truly extraordinary’ by the late Benedict Anderson, the prominent Indonesia scholar.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: A portrait of President Soeharto of Indonesia, taken in 1978 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): A portrait of President Soeharto of Indonesia, taken in 1978 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): David Reeve reviews 'Young Soeharto: The making of a soldier, 1921–1945' by David Jenkins

- Book 1 Title: Young Soeharto

- Book 1 Subtitle: The making of a soldier, 1921–1945

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $39.99 pb, 547 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/NKYQ6K

President Soeharto has been a preoccupation throughout David Jenkins’s life. Jenkins conducted a first, nervous interview with the newish president in November 1969, and was treated with affable caution (described in the preface). At a later meeting, he was embarrassed by an unexpected wedding gift from Madame Soeharto, creating a dilemma about accepting a gift from a foreign head of state. (Of the two versions of his name, Suharto/Soeharto, Jenkins argues for the ‘old’ Dutch spelling Soeharto, which the president himself favoured.)

Jenkins went on to various countries and positions, in Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand; he was foreign editor and then Asia editor of the Sydney Morning Herald. One posting back in Indonesia from 1976 to 1980 resulted in his book Suharto and His Generals: Indonesian military politics, 1975–1983. This book demonstrated the author’s astonishing access to a great many senior figures in the military, and the startling candour with which Jenkins managed to get them to talk. Jenkins’s ability to persuade senior figures to talk openly is a hallmark of the new volume.

In 1986, a Jenkins article on the Soeharto family’s wealth in the Sydney Morning Herald caused a short crisis in Indonesian-Australian relations; a planeload of tourists was even turned back from Bali. David Jenkins was not allowed back to Indonesia until 1993.

This volume joins a substantial list of previous works about Soeharto. There have been several major works, including O.G. Roeder’s The Smiling General in 1969, R.E. Elson’s Suharto: A political biography (2001), Angus McIntyre’s The Indonesian Presidency (2005), various long form press articles, and Soeharto’s own accounts, particularly My Thoughts, Words and Deeds, in English and in Indonesian, in 1989. Nonetheless, there remain many unresolved issues about events in Soeharto’s life, partly arising from contradictions between the claims made by Soeharto and his associates, and by others more critical.

Jenkins argues that not enough has been written about Soeharto’s early life and career up to 1965, and that his rule from 1966 to 1998 can only be understood in the light of a ‘richer, more nuanced portrait’ of the kind of man he was and the profound impact of his early years. These three volumes (two more will follow shortly) have a double purpose: first, to provide the definitive Soeharto biography; and second, to retell the story of the Indonesian nation: ‘an accessible introduction to the many factors that have shaped and continue to shape Indonesia, the story of how a new nation came into being … and how it made its way in the world’. Soeharto’s life, ‘through a fortuitous combination of birth, geography, training and circumstance’, was interwoven with key events of modern Indonesian history, and thus provides a connecting thread between the biography of an individual and that of the nation. As part of both these stories Jenkins evokes the various ‘worlds’ in which the young Soeharto lived and operated: Javanese, Islamic, Dutch colonial, and Japanese modern and military.

This volume is based on Soeharto’s first twenty-four years – the troubled childhood and adolescence, the Dutch colonial army in 1940, followed by service under the Japanese Occupation as a policeman and then a soldier – but is not restricted to them. Jenkins moves back and forth across the whole life, depending on where he sees relevance and continuities. The preface starts with the events in 1965 that brought Soeharto to power; the fourteen succeeding chapters move in similar ways across the decades. This volume has many sharp evaluations of the man and the whole of his career; for example these two of many:

an outsider who overcompensated for the difficult hand that life had dealt him, who trusted only his family and his closest colleagues, who was obsessive in his attention to detail, ruthless in his pursuit of objectives and indifferent to considerations of propriety.

A man of resourcefulness and guile, an enigma even to his closest associates, obsessed with stability, order and economic development, finding relaxation in farming, golf and deep-sea fishing …

Jenkins is always trying to explain how this figure, with such a disordered and unhappy childhood, modest social origins, and limited education, should throughout his career unexpectedly surpass so many other leaders, military and civilian, who were better educated and more sophisticated.

In making his judgements, Jenkins includes a range of comparisons with other leaders. One line is a comparison with other tough and successful Asian leaders, Lee Kuan Yew in Singapore, Park Chung Hee in South Korea, and Deng Xiaoping in China. Jenkins sees Soeharto as one of the most complex and important Third World leaders since 1945. Another line is broader and more historical, comparing Soeharto to General Pinochet of Chile, General Franco of Spain, then Bismarck and particularly Napoleon. There is also a comparison to Lyndon Johnson. As part of his continuing commentary on the Javanese ‘world’, Jenkins compares Soeharto to Javanese sultans and princes.

There are for me three great strengths to this book, where the writer’s delight communicates itself to the reader. The first is Jenkins’s late-career delight in the huge volume of interview and archival material – astonishing, massive, across Indonesian, Dutch, Japanese, British, and Australian sources. The second is Jenkins’s pleasure in selecting from all this material to make narratives, analyses, and evaluations about Soeharto’s career and Indonesian life. The third is the veteran wordsmith’s delight in polishing these selections into vivid and striking accounts. As the young Soeharto moves from place to place, and upwards within organisations, Jenkins provides thumbnail sketches of each step with unprecedented clarity and detail. These strengths are particularly evident in the masterly coverage of the twists and turns of the Japanese Occupation of Indonesia (1942–45), which takes up the second half of the book, chapters eight to fourteen. There is also, occasionally, a dry wit that I hope to hear more in the later volumes.

So far, one volume in hand, I think there is little about ‘how a new nation came to being’ that is unfamiliar, but there is plenty of new information about the man and how he was shaped as a leader, and much that is of interest in the vivid, gritty accounts of Soeharto’s career. This volume, a fine read in itself, thoroughly whets the appetite for what is to follow.

Comments powered by CComment