- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The amateur librarian

- Article Subtitle: Inside Stalin’s library

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The books we read and collect can provide telling insight into our lives. Indeed, bookshelves often draw the immediate attention of our guests, who seek to discern clues about us from the titles that we have accumulated. With Stalin’s Library: A dictator and his books, Geoffrey Roberts takes on the role of a curious visitor perusing the impressive library of Joseph Stalin (1878–1953), who, as head of the Soviet Union, amassed a collection of some 25,000 items. Conceptualised as a biography and intellectual portrait, Stalin’s Library joins a crowded field of works aimed at cracking the Stalin enigma. Setting this latest biography apart is its focus on Stalin’s personal library as a basis for constructing a ‘picture of the reading life of the twentieth century’s most self-consciously intellectual dictator’.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

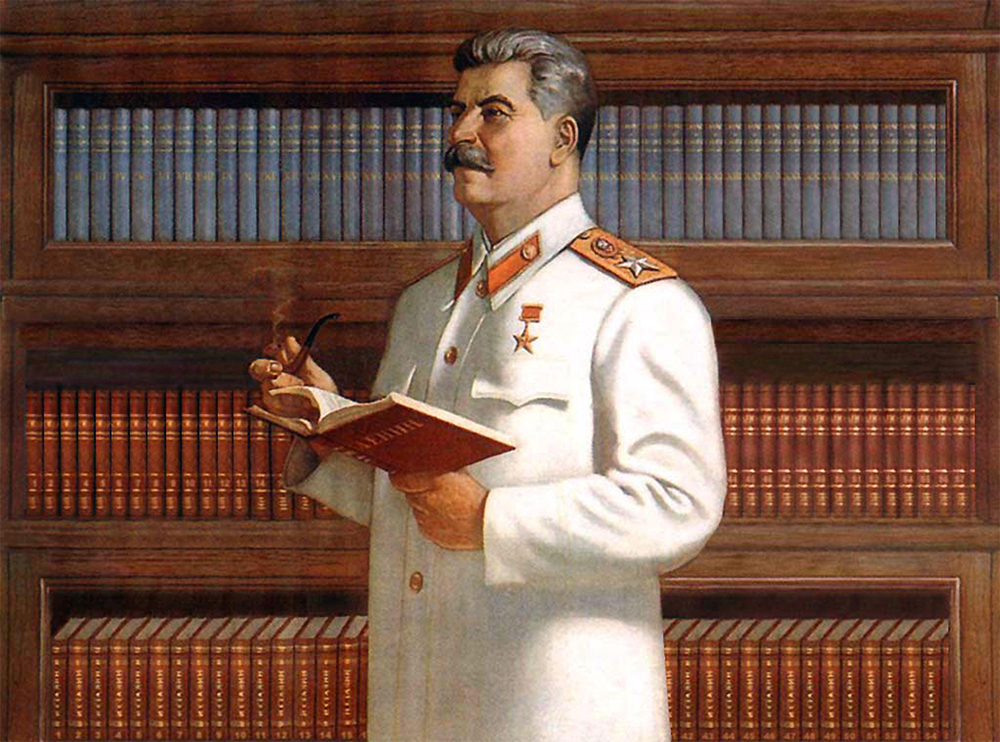

- Article Hero Image Caption: A portrait of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin in his library, c.1943 (photograph via Alamy)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): A portrait of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin in his library, <em>c</em>.1943 (photograph via Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Iva Glisic reviews 'Stalin’s Library: A dictator and his books' by Geoffrey Roberts

- Book 1 Title: Stalin’s Library

- Book 1 Subtitle: A dictator and his books

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press, US$30 hb, 268 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/jWjnn5

‘A dedicated reader and self-improver’, during his thirty years in office (1922–53), Stalin collected books on a vast array of topics, with an emphasis on history (his favourite subject), Marxism, and the classics of Russian and Western fiction. Following his death – on a couch in the library at his dacha – the collection was dispersed among various institutions. Drawing on Stalin’s file in the Communist Party archive, memoirs of his contemporaries, and a number of existing biographies, Stalin’s Library is an attempt both to reconstruct the Soviet statesman’s personal library and to understand him as a Bolshevik intellectual.

Constructing Stalin’s biography through a study of the dictator as a reader, writer, editor, and occasional plagiariser is an attractive proposition. The potential of this approach is, however, only partially fulfilled, as Stalin’s Library stays largely on a well-trodden path. In noting, for example, that Stalin spent his formative years at the Tbilisi Spiritual Seminary, Roberts insists that ‘there was no book that he studied more than the Bible’. From here the book takes an excursion into conventional accounts of Bolshevik attitudes toward religion, their relationship with the Orthodox Church, and scholarly interpretations of communism as a political religion. Ensuing sections follow a similar structure, in which books often function simply as entry points into familiar historical episodes.

Readers well versed in Soviet history will find more novel content beginning at chapter four, which opens with an exploration of the classification scheme that the Soviet leader devised for his book collection. Roberts depicts Stalin as an amateur librarian, organising items by author and subject matter – from art criticism to trade unionism – with works produced by his political rivals especially prominent. Focus then shifts to Stalin’s librarians and Kremlin offices, apartments, and Moscow dachas where his book collection was housed. Stalin’s less than exemplary book-handling habits are also foregrounded, with Roberts drawing on anecdotes about greasy finger-marks left on borrowed books, and stacks of unreturned library items.

This portrait of Stalin the librarian leads into an analysis of a distinct portion of the collection, comprising some 400 publications with his annotations. The range here is broad, with Roberts moving from Stalin’s marginalia in books by former foreign intelligence agents, to the dictator’s close reading of the memoirs of Otto von Bismarck, the American Constitution, and the writings of his arch-enemy, Leon Trotsky. Though it provides intriguing insight into the books that captured Stalin’s attention, this chapter – which makes up almost a third of the book – is overloaded and again dominated by long digressions into Soviet history.

A one-time poet, Stalin maintained a lifelong interest in literature, with his library known to have contained thousands of novels, plays, and volumes of poetry. Yet as Roberts explains in a chapter on Stalin and fiction, we do not know precisely which literary works were held in his library, as this portion of the collection was largely dispersed after his death. In the absence of this information, Roberts builds a profile of Stalin as a reader of fiction based on inferences drawn from his interventions into cultural policy, engagements with Soviet writers, and deliberations on awarding the State Stalin Prize in arts. This research reaffirms Stalin as a reader of conservative taste.

More revealing is the final chapter, which examines a set of publications predominantly concerned with Soviet history that Stalin contributed to, critiqued, or edited. This section highlights Stalin’s lifelong passion for history – a thread that Roberts weaves throughout the book – and includes discussion of Stalin’s interventions into academic debates in this field, and his contributions to publications such as History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union: Short course and History of Diplomacy. A keen interest in the past was also at the heart of Stalin’s aesthetic judgement, with writers and filmmakers placed in the crosshairs when their work did not contain ‘enough history’. This image of Stalin as historian-in-chief stands out in Roberts’s account, and highlights the centrality of the discipline within Soviet political culture.

While Stalin’s library remains a promising lens to examine the dictator and his era, many of the potential avenues offered by this framework remain unexplored. The book as a material object – and indeed, one that was the subject of significant innovation during the Stalinist era – is not considered, and nor is there any engagement with the frequent visual representation of Stalin within his library. Furthermore, though noting that Stalin’s collection also extended to maps and gramophone records, Roberts does not expand on these items, or examine their connection to Stalin’s image as an intellectual. Although certainly more digestible than many of the hefty volumes that have become a hallmark of this genre, Stalin’s Library in many respects remains a conventional biography. Whether there is space for a copy in your own library will depend on your familiarity with its well-worn subject matter.

Comments powered by CComment