- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A league of his own

- Article Subtitle: Stuart Macintyre’s final volume

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Stuart Macintyre was in a league of his own as a historian of communism. That’s not just a comment on his status as a historian of the Communist Party of Australia, whose first volume, The Reds (1999), took the party from its origins in 1920 to brief illegality at the beginning of World War II, and whose second, The Party, covering the period from the 1940s to the end of the 1960s, now appears posthumously. It applies equally to his stature in the international field of the history of communism. There are plenty of Cold War histories of the communist movement, written from outside in severely judgemental mode. There are also laudatory histories, written from within. But when The Reds appeared, it was, to my knowledge, the first history of a communist party anywhere that succeeded in normalising it as a historical topic, that is, writing neither in a spirit of accusation or exculpation but with critical detachment and scrupulous regard for evidence and its contradictions.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Jim Healy’s funeral procession (State Library of New South Wales, PXA 593 [v.38], Courtesy SEARCH Foundation, from the book under review)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Sheila Fitzpatrick reviews 'The Party: The Communist Party of Australia from heyday to reckoning' by Stuart Macintyre

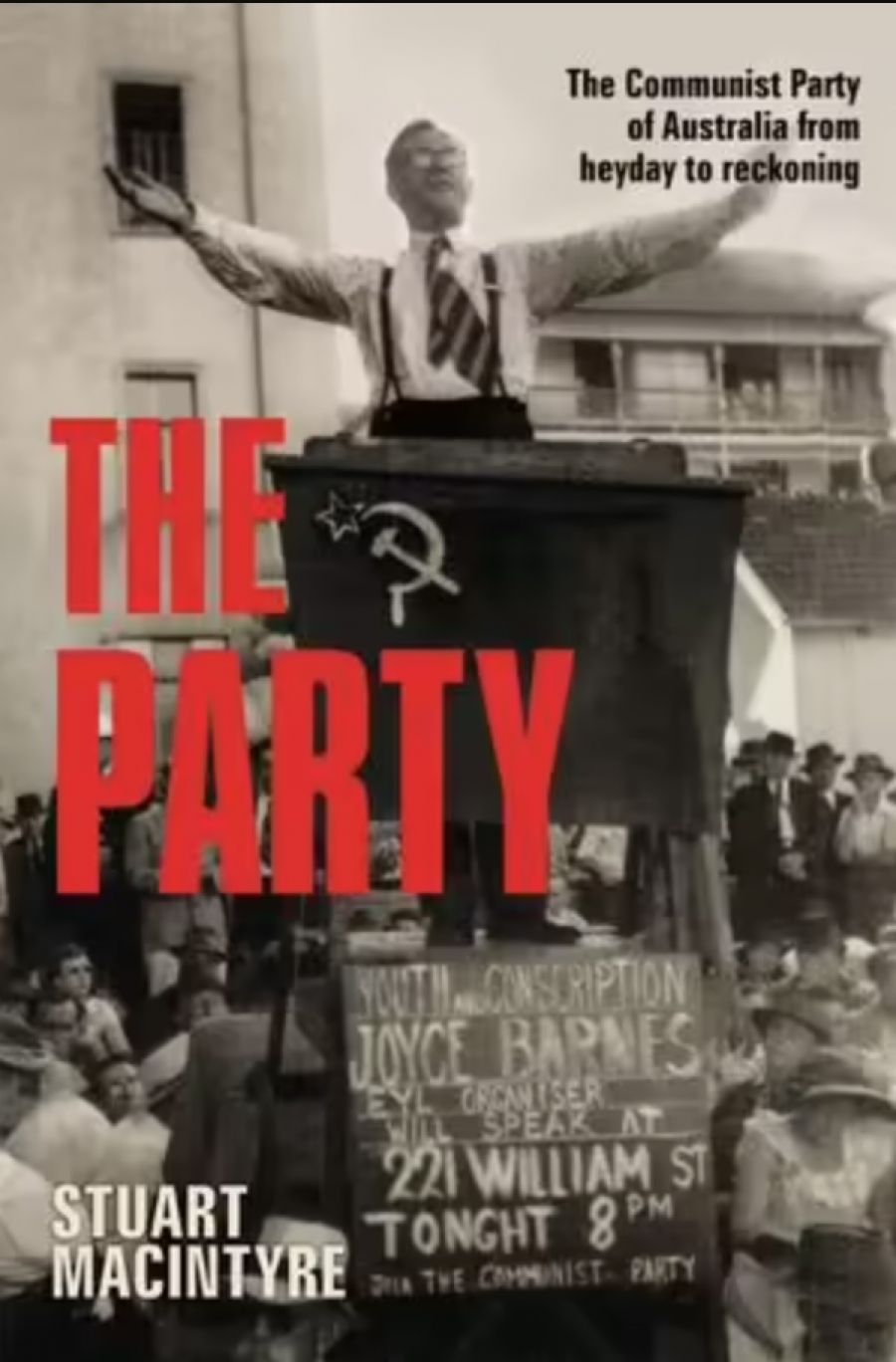

- Book 1 Title: The Party

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Communist Party of Australia from heyday to reckoning

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $49.99 hb, 422 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/5bBb6b

Some might say this is an old-fashioned historical method. In the first place, they would say, advocacy (the alternative method) plays a moral role in exposing evil and helping to redress historic injustices. In the second place, historians always have their biases, so they might as well reveal them. Macintyre (who once edited a book called The Historian’s Conscience, 2004) was a historian to whom the moral question mattered, but he thought that part of the historian’s moral imperative was not to distort the evidence to support a one-sided picture. As for his own potential biases, he makes sure the reader knows about them by identifying himself up front as a youthful communist (of 1968 student revolution vintage) who, after a decade, left the party but remained a socialist. That done, he sets out to trace the party’s postwar history in his historian’s voice – detached, critical, but also empathetic.

The Reds was a story of success, of a marginal political group gathering a bit of traction during the Depression and then, after the brief period of illegality, experiencing a dramatic rise in popularity and influence during World War II. The connection with Moscow and its international arm, the Comintern, had previously caused problems as Moscow periodically reversed course on crucial issues such as whether communist parties could cooperate with other parties of the left. The Soviets’ 1939 Non-Aggression Pact with the Nazis left communists in Australia, as elsewhere, particularly off balance. From 1940–42, the party was formally illegal in Australia, but its emergence from semi-underground seems only to have added momentum to its subsequent wartime success – tripling of membership to more than 20,000, high national visibility, considerable influence in the trade unions, and a surprising ability to keep on good terms with the governing Labor Party.

The Party, by contrast, is a story of decline and fall, starting with the high point at the end of the war, running through the successive setbacks and disasters of the Cold War, and ending with disillusionment with Moscow and a return to marginality at the end of the 1960s. By 1949, party membership was half what it had been at the beginning of the decade, and it had dropped further to four to five thousand by the mid-1960s. The glory days of the mid-1940s are eloquently evoked by Macintyre’s prose, but for anyone who lived through the Cold War it is an image that has the most shock value: the plate between pages 242 and 243 showing a five-storey building on Sydney’s George Street with a sign visible from afar that proudly reads ‘AUSTRALIAN COMMUNIST PARTY CENTRAL COMMITTEE’. That building, bought by the Communist Party for £30,000 in 1944 and named ‘Marx House’, had once housed a bookshop, a cafeteria, and lecture halls, as well as party offices. It was sold in 1949, after a raid by the Commonwealth Investigation Service, an event soon followed by the breaking of the miners’ strike that marked the beginning of the end for the Communist Party.

Marx House (National Archives of Australia, A705 171/94/413, from the book under review)

Marx House (National Archives of Australia, A705 171/94/413, from the book under review)

As Macintyre points out, the Cold War – when anti-communism became a defining characteristic of Western democracy – arrived later in Australia than in the United States and the United Kingdom. But by 1949 its presence was pervasive: calls for a ban on the Communist Party were gaining traction, though still resisted by the Chifley government, and the Victorian state government launched a Royal Commission on communism. Labor’s defeat in the 1949 federal election brought in the Menzies government, which, with the advent of the Korean War, declared Australia to be at war with international communism. The Australian Communist Party came under close surveillance by the new and tougher Commonwealth security service that had replaced CIS – the Australian Security and Intelligence Organisation (ASIO), headed by Colonel Spry. In April 1950, Menzies introduced the Communist Party Dissolution Bill, and the party prepared for a new period of illegality. Unexpectedly, the referendum on the bill failed, and the party remained legal – just. In 1954 came the defection of a Soviet diplomat and undercover intelligence agent, Vladimir Petrov, prompting a Commonwealth Royal Commission on Espionage in which a spy ring headed by Communist official Wally Clayton was named and the party’s reputation hopelessly tarnished.

In the next phase of the party’s story, mainly out of the public eye, internal problems come to the fore. Moscow’s authority in the international communist movement was eroded in 1956, first by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin’s crimes and then by the sending of Soviet troops to Hungary to keep the satellite state in line. The Sino-Soviet split followed at the beginning of the 1960s, with Mao Zedong offering a challenge and alternative to Soviet ideological primacy. The sending of Soviet troops to Czechoslovakia in 1968 was the last straw for many Australian communists.

Drawing on Communist party records held by the Search Foundation, the records of ASIO’s detailed surveillance held in the National Archives of Australia, and extensive interviews with former and present party members, The Party gives a definitive account of the history of the Australian Communist Party from World War II to the beginning of the 1970s, encompassing its role in Australian politics, its relationship with the Soviet Union, and its internal factional struggles. But that is not all. One of Macintyre’s central purposes in writing The Party was to capture the lived experience of being a party member. That experience included voluntary submission to a strict disciplinary regime – essentially self-discipline, as Macintyre points out, since Moscow had no real means of enforcing obedience – and a lot of ritual obeisance. It included idealistic willingness to make sacrifices for the cause, which, to its adherents, meant not only power to the workers but also defence of the rights of women, Aboriginal Australians, and other oppressed groups; support of colonial liberation and international peace movements; opposition to the White Australia policy; community plans for neighbourhood improvement; and a range of ‘progressive’ initiatives.

For working-class members, the party offered education and self-esteem; ‘changed us from headbutting incompetents to thinking strategists’, as one long-time member put it. Its members felt that their lives had meaning because history was on their side. In the 1950s, with the Soviet Union no longer either a Western ally or an unchallengeable moral authority, ‘the correlation between history and communism began to come unstuck’. That was the product of external developments, but overall The Party is definitely an Australian story. Perhaps 100,000 Australians were party members at some time in their lives (dropping out was as much part of the typical experience as joining). In the last sentences of his book, Macintyre seems, uncharacteristically, to be striking a note of pathos: ‘Now ageing, those who joined in the 1940s could still recall the mass rallies during the war against fascism, the spectacle of national congresses that filled the Sydney Town Hall, the hundreds of community plans distributed at the end of the war, the meaning and purpose they found in carrying out their duties.’ But immediately there is a wry switch (or double switch) of tone: ‘Sooner or later, the overwhelming majority [of party members] left, but not before leaving their mark on this country.’

Stuart Macintyre himself, one of the great Australian historians of his generation, certainly left such a mark. We can only be grateful that, refusing to bend to the cancer that killed him in late 2021, he managed to finish this book. Nobody else could have written it.

Comments powered by CComment