- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The man in the mirror

- Article Subtitle: Texture and nuance in the new biography of Bob Hawke

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Curators at old Parliament House – now known as the Museum for Australian Democracy – have for many years maintained the prime minister’s suite much as it was when Bob Hawke vacated it in 1988. Visitors can gaze at a reproduction of the Arthur Boyd painting that hung opposite Hawke’s desk, gawk at the enormous, faux-timber panelled telephone Hawke used, and cast a wry eye over the prime ministerial bathroom, where curators have laid on the vanity toiletries and accoutrements belonging to the office’s last occupant: a box of contact lenses, a pair of black shoelaces, and a tube of hair dye.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

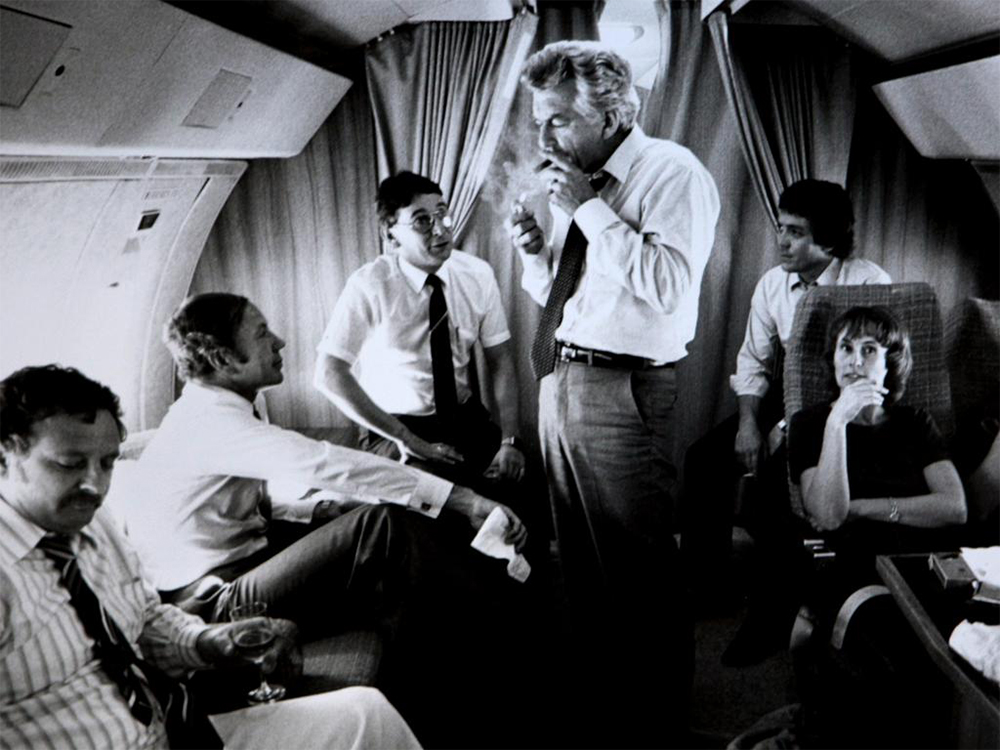

- Article Hero Image Caption: Bob Hawke on his campaign plane, 1983 (Ray Strange/News Corp Australia, from the book under review)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Patrick Mullins reviews 'Bob Hawke: Demons and destiny' by Troy Bramston

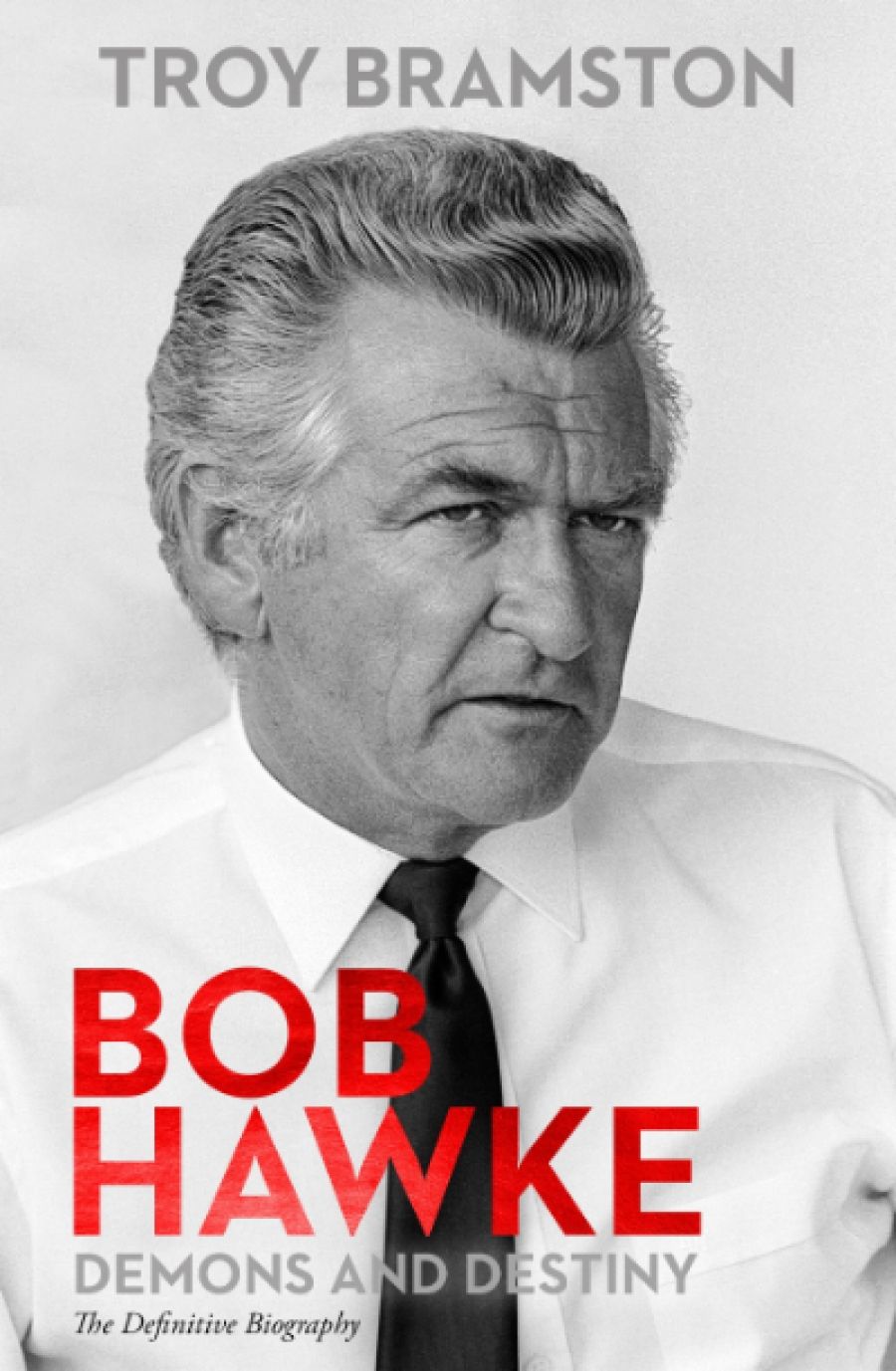

- Book 1 Title: Bob Hawke

- Book 1 Subtitle: Demons and destiny

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $49.99 hb, 704 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/a1Z10N

Hawke was a man famously obsessed with appearances. To look more ‘prime ministerial’ in the 1980s, Hawke cut his hair, trimmed his sideburns, swapped his glasses for contact lenses, his suede shoes for leather, and wore only tailored suits. He also took care to shape how his character was presented to the Australian electorate. The subject of two biographies while president of the ACTU (1970–1980), Hawke gave his blessing to his sometime lover Blanche D’Alpuget to write his biography anew in 1979, shortly after he announced that he would stand for Parliament. Over the subsequent two and a half years, he pressured her on his representation in the book, particularly on his being a ‘reformed character’ who had given up grog and womanising ahead of fulfilling a long-awaited destiny to lead the country. The resulting biography, published in 1982, predated Hawke’s becoming leader of the Labor Party by four months, and his becoming prime minister of Australia only by five. As an exercise in public relations or prophecy, it was brilliantly executed.

Writing in that book’s foreword, D’Alpuget speculated that a biography written after Hawke’s death might be very different; in Bob Hawke: Demons and destiny, we now have that biography. Troy Bramston, a writer for The Australian and author or editor of ten other books, offers a detailed and assiduously researched account of Hawke’s life and legacy. It is accessible, comprehensive, and, as with his 2016 biography of Paul Keating, likely to become authoritative for all things Hawke-related. Given the already groaning shelf of books on or related to Hawke – from the aforementioned biographies to the political histories of Paul Kelly, among others – the question that must be answered is what additional value does Bramston’s book provide. How different is it from the other books?

Bramston answers this by stressing the voluminous sources that inform his work, by his presentation of Hawke’s considerable personal failings, and by arguing that there is a need to better understand Hawke and the government he led between 1983 and 1991. Bramston has interviewed more than one hundred people and draws on archives that are far-ranging, including the diaries of former US presidents and correspondence between Australia’s governors-general and the queen. Some sources, such as Ronald Reagan’s diaries, are unilluminating, but in the main Bramston’s industriousness gives the book texture and nuance, with conflicting and distinct voices sometimes offering earthy counterpoints, withering assessments, and subtle riches. He delves into Hawke’s love life, detailing his numerous affairs – including in those with Jean Sinclair, his longtime office manager, and with D’Alpuget, including the period when she was writing the Hawke biography – and the controversies that followed Hawke, such as the allegation that he covered up, for political advantage, a sexual assault against his own daughter. Recounting many instances of Hawke’s sharp tongue and belligerence, his loathsome drunken behaviour, his infidelities and crude sexism, and what seems a heartless disregard for his family, Bramston writes that Hawke’s behaviour ‘would not be tolerated today’.

That it was tolerated for such a long time tells us much about both the times in which Hawke rose to prominence and the significance of the talents he could wield. His joining the ACTU in 1958 as a research officer and advocate gave that organisation a vital shot of energy and intellectual rigour as it pushed for increases in wages and working conditions before the courts and the Conciliation and Arbitration Commission. Hawke’s ascent in the ACTU, and his growing public profile over the next two decades, was fuelled by his success in those fora, an immense work ethic, and a willingness to give journalists a comment on anything and everything, whether wages, economic policy, or the kind of women he liked. He became president of the ACTU in 1970, president of the Labor Party in 1973, and was fêted as someone with the ability to lead the country. Hawke was never averse to pushing that barrow: ‘If I did go across to the parliamentary side of things, being the sort of human being I am, I’d aim for the top.’

Bramston’s account of how Hawke went into parliament, and of the efforts he put into getting to the top, is familiar but compelling. He adds valuable detail about the deal struck with Bill Hayden when the latter stepped down as Labor leader in February 1983, though he does not remark on the ramifications of Labor’s ‘whatever it takes’ approach to winning office that the change heralded. Bramston does not dwell too much on Hawke’s decision to go on the wagon, but he points out that Hawke’s infidelities, while moderated, continued and were facilitated by his minders: ‘He just expected discretion from everybody,’ recalled the head of Hawke’s security team. Bramston’s rigour and detail are often impressive, but occasionally his claims are wanting in interrogation. Was Hawke really a sex addict, as Bramston claims? Was he a narcissist? Many have said yes to the latter, but Bramston gives a one-line answer in the negative that warrants much more elaboration.

Bramston’s admiration for the Hawke–Keating governments has long been well known, and here he shows the reasons for that admiration: the government’s discipline, its reforms of Australia’s economic and social fabric, and its centrist approach to building consensus did much to ensure its longevity in office and enduring impact. The achievements of the Hawke government are many and impressive, and while this is well-trodden ground, Bramston does his best to find the areas in which Hawke’s influence is notable. Perhaps most striking in this regard, given Hawke’s casual sexism in his pre-parliamentary career, was his support for Susan Ryan and Anne Summers’ efforts on anti-discrimination and childcare reform: ‘He was intellectually disposed to understand and agree with the need for any civilised society to ensure that women were not discriminated against and could pursue any opportunities of their choosing,’ said Summers later.

What is also interesting is the account of Hawke’s post-prime ministerial life, which saw his public standing plummet and then, in the 2000s, rise. The first was caused by Hawke’s naked commercialism, his divorce from Hazel Hawke in 1995 and marriage to D’Alpuget, and his bitterness over his loss of the prime ministership to Keating, most evident in The Hawke Memoirs. Hawke’s recovery came from the passage of time, the recurring disregard in Australia for contemporary political pygmies and nostalgia for the supposed giants of the past, and an assiduous burnishing of the Hawke government’s legacy. As a result, blemishes were wiped away and complexities reduced to simple platitudes. Hawke was presented more as a celebrity and larrikin, sculling beers or sipping milkshakes, than elder statesman. As Bramston writes, ‘the myth almost overshadowed the real man’. In the past decade, the combination of a telemovie, a hagiographic account of his prime ministership by D’Alpuget, and various ‘soft’ documentaries and interviews on television and in print has seemingly given Hawke a halo that will not be dislodged.

Not altogether different in tone from D’Alpuget’s 1982 biography, Bramston’s nonetheless adds shade and colour to Hawke’s saintly glow. What emerges particularly strongly – both in the extensive co-operation afforded to Bramston and the cumulative effects of all this historiography – is Hawke’s ongoing effort to curate his image and control his legacy: a man looking in a mirror, endlessly trying to adjust what is reflected back.

Comments powered by CComment