- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Style and bounce

- Article Subtitle: Examining the history of AGNSW

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Western, colonial, patriarchal hegemony having eroded somewhat in recent years, the purposes and methods of art and of museum management and curatorship are undergoing fundamental change. Formerly unchallenged Anglophone-transatlantic canons and practices have been undermined by broader international perspectives, by the impact of digital technologies, and by the politics of identity – in ethnicity and nation, gender and sexuality.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: US President Lyndon B. Johnson surrounded by security personnel arriving at the New South Wales Art Gallery on a visit to Sydney, 22 October 1966 (photograph: John Mulligan, National Library of Australia)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): US President Lyndon B. Johnson surrounded by security personnel arriving at the New South Wales Art Gallery on a visit to Sydney, 22 October 1966 (photograph: John Mulligan, National Library of Australia)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): David Hansen reviews 'The Exhibitionists: A history of Sydney’s Art Gallery of New South Wales' by Steven Miller

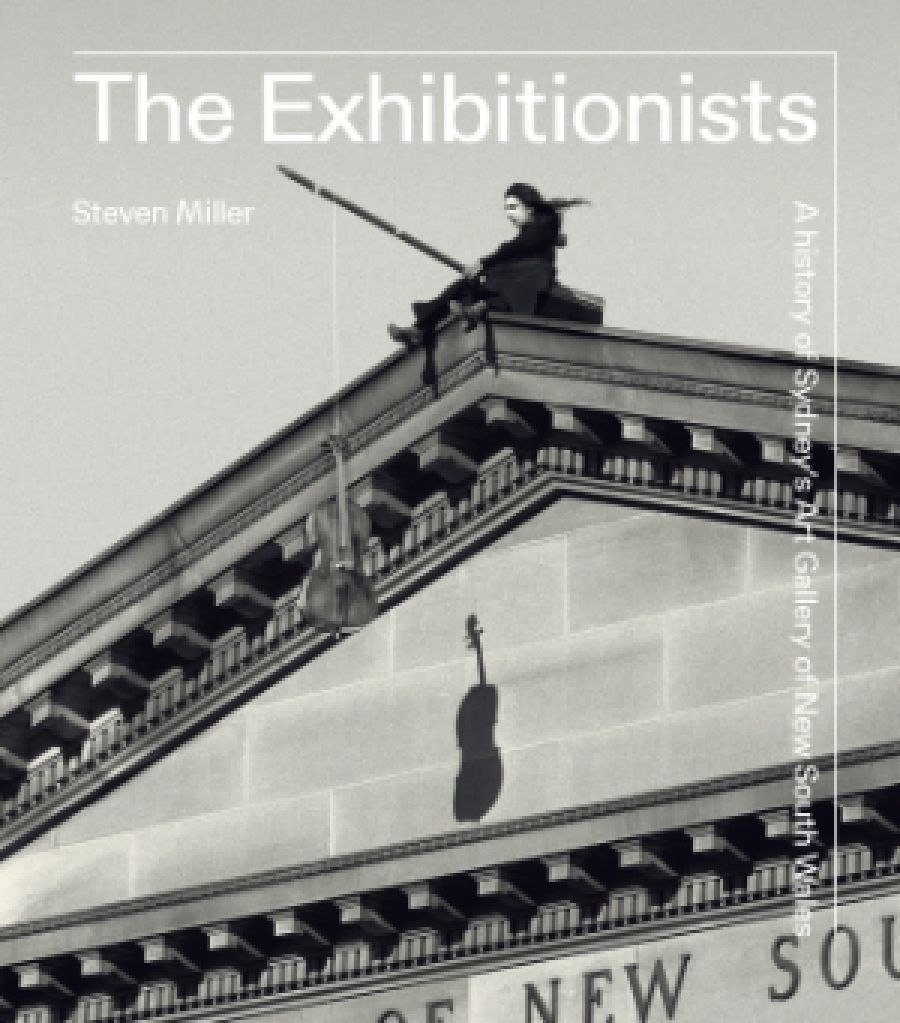

- Book 1 Title: The Exhibitionists

- Book 1 Subtitle: A history of Sydney’s Art Gallery of New South Wales

- Book 1 Biblio: Art Gallery of New South Wales, $65 hb, 295 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/0JOPV3

The two key questions for the contemporary art museum are how to continue to assess, translate, and understand the art of the past while re-examining and redefining it in relation to contemporary concerns, and how best to participate in creating, presenting, and interpreting the object- and image-worlds of the present.

Something of the challenges of the present moment for museums can be gleaned from the title of this volume. According to the acknowledgments, The Exhibitionists was suggested by AGNSW’s Creative and Content Coordinator, Marketing. Not only was such a role virtually unheard of twenty years ago, but the implied emphasis of the text on exhibition programming contradicts both former Director Hal Missingham’s belief that ‘a true history of the Gallery would be, above all, a history of its collections’, and the stated ambition of the author to track the ‘people and events that have shaped the Gallery’. Less significantly, but peculiarly, the subtitle is A history of Sydney’s (my emphasis) Art Gallery of New South Wales, a redundant formulation with odd echoes of tourism destination promotion.

Consider the photograph that introduces the book’s first chapter, ‘Resilience and Defiance’. Documenting a 2019 work in the Unbound Collective’s Sovereign Acts trilogy, it shows Antikirinya/Yankunytjatjara academic Simone Ulalka Tur walking in ceremonial processional through the neoclassical architecture of Walter Vernon’s hexastyle stoa at the Gallery’s entrance (designed 1896, completed 1902), with, in the background, British artist Gilbert Bayes’s wartime The Offerings of Peace (commissioned 1915, completed 1923). On AGNSW’s Facebook page, the appropriate description of ‘relationship status’ – with First Nations, with the Enlightenment-classical tradition, or with British heritage – would have to be: ‘It’s complicated.’

That said, the history of the AGNSW – in all its copiousness and complexity, its confusion and occasional (okay, regular) conflicts – is told here with style and bounce and intelligence. Across nineteen discrete and manageably brief chapters, Steven Miller traces the lives of the institution in roughly chronological sequence, though several of his sections have a thematic emphasis which permits a certain amount of illuminating time travel.

In keeping with the spirit of the times, attention is given throughout to previously marginalised constituencies. ‘Resilience and Defiance’ acknowledges that ‘wherever there has been settlement … there has also often been an erasure or, if not, a forgetting. The Gallery … wants to remember.’ Miller’s account not only describes First Nations–settler cultural disconnection but also how it has manifested itself in various acquisition decisions.

In the ‘know my name’ present, women, too, receive long overdue attention, from the illiterate, ‘no-nonsense’, nepotistic caretaker Margaret Casey, appointed as the Gallery’s first member of staff in 1875, to the sensitive and delicate Adelaide Ironside, whose The Marriage at Cana was first loaned to the Gallery in 1877. We meet New Zealand-born, Melbourne-trained Grace Joel, whose work was never purchased by the Gallery, although it accepted portraits of two male artists – Arthur Streeton and G.P. Nerli – that she bequeathed on her death in 1924, as well as the redoubtable Dora Ohlfsen, whose 1913 commission for a bronze panel above the Gallery’s front doors was unaccountably cancelled in 1919. At the time, Trustee John Sulman warned Director ‘Vic’ Mann that ‘Miss Ohlfsen is a woman, and although she has no case, can cause mischief.’ Other necessary mentions include the artistically and politically progressive Mary Alice Evatt, first female Trustee (appointed 1943), a raft of eminent recent curators – Renee Free, Frances McCarthy, Jackie Menzies, Bernice Murphy, Gael Newton, Hetti Perkins, and Deborah Edwards – and, of course, the gallery’s great artist–benefactor Margaret Olley.

As such references (and a comprehensive scholarly apparatus) attest, Miller, head of the Gallery’s National Art Archive and its Edmund and Joanna Capon Research Library, has a sharp eye for the telling incident, object, or manuscript. He clearly relishes the newspaper description of the 1904 marble staircase to the basement gallery as having been ‘executed under the shade of the gallows’, using prison labour from Bathurst Gaol. Apropos of mortality, we also learn that the marble top of the painting conservators’ canvas-lining table came from the Sydney Hospital morgue. We encounter the perils of research – Director’s secretary Gwen Sherwood complaining formally to Trustees that the press-cutting books were ‘being depleted by Mr Bernard Smith’ (the young Education Officer being then engaged in writing Place, Taste and Tradition) – and of commercial activity in the Gallery, notably the damage caused by the thousands who attended the 1972 International Congress of Accountants conference party. Closer to our own time, we are told of the charismatic Edmund Capon (whose thirty-three-year directorial tenure earns him two chapters) facilitating tourist visits by organising a free after-hours preview of the 1984 Picasso exhibition for taxi drivers and their families, and ordering the Gallery’s Australian flag lowered in protest at Australia’s involvement in the 2003 Iraq war. There is little discretion in Miller’s quotations: Curator of Prints and Drawings Nicky Draffin characterises Van Gogh’s Head of a Peasant as ‘finger painting in shit’, while Capon describes advocates of admission fees as ‘arseholes and dickheads’.

Of course, words are only for those who can’t read the pictures, and The Exhibitionists is copiously illustrated, not only with the predictable vintage photographs, architects’ plans, and works of art from the collection, but with surprising, delightful reproductions: a decorative header for an 1888 Illustrated Sydney News article on the Gallery (surely by Charles Conder); Kubota Baizen’s rendering of Julian Ashton’s The Prospector, from the Japanese catalogue of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago; a 1904 Operative Stonemasons’ Society union banner featuring an image of the Gallery façade; and Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s signature in the Visitors’ Book. From later in the twentieth century we see interiors of the caretaker’s cottage, a Captain Cook Bi-Centenary Foundation Appeal commemorative plate; Tim Burns’s 1972 poster Fuck Laverty and the Trustees; LBJ arriving at AGNSW surrounded by security personnel; and Capon mugging for the press from the bucket of Ange Leccia’s wheel loader installation Komatsu, arrangement at the 1990 Sydney Biennale.

In our anxious, pre-post-colonial, global-digital age, the importance of the visible and the material – of archival encounter, of first-hand, authentic experience, of what the German novelist Siegfried Lenz called in his 1978 novel The Heritage ‘the unimpeachable testimony of objects’ – cannot be overstated. Miller gives us this in spades. And he demonstrates that for all the diversion and distraction of the Archibald Prize, for all the years of edifice complex, for all the occasional conservatism, for all the missed acquisition opportunities and misguided deaccessions, so too, does the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Comments powered by CComment