- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

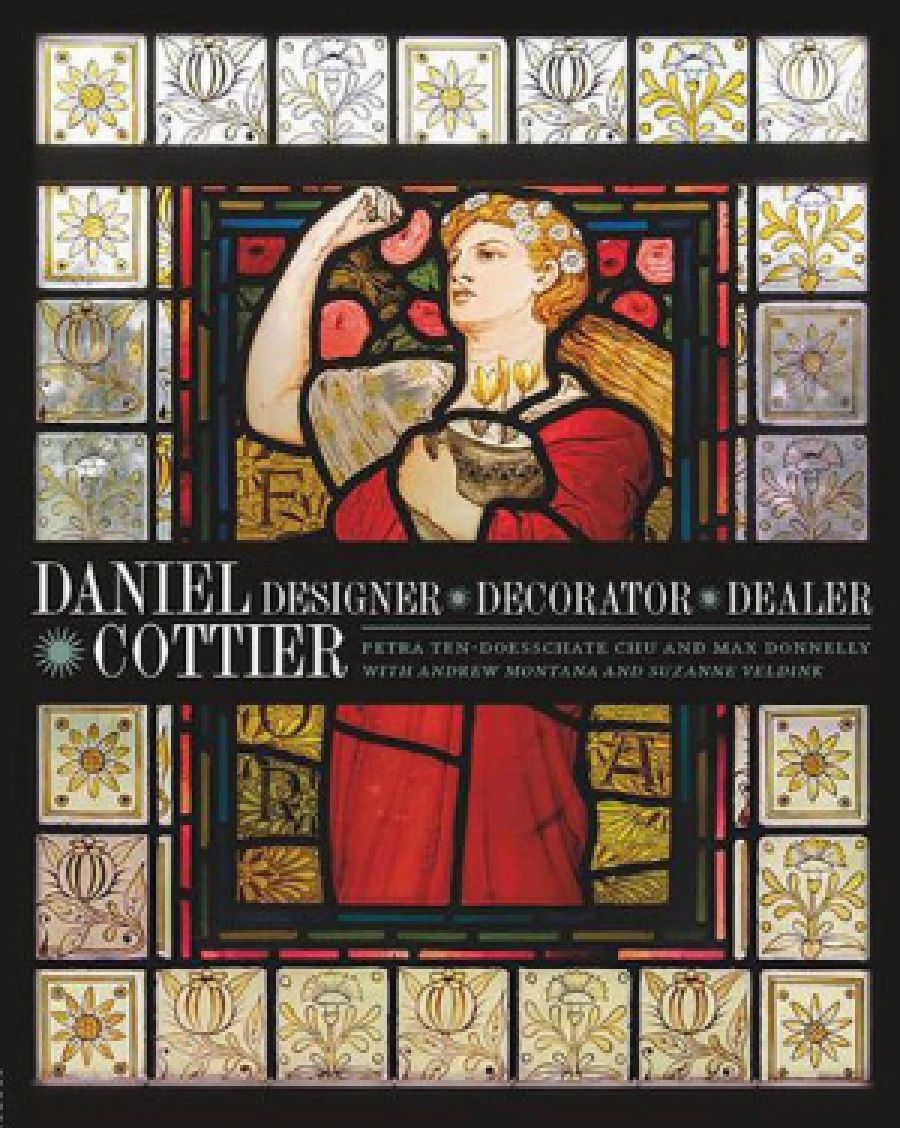

- Article Title: Realising the ‘home beautiful’

- Article Subtitle: The first scholarly study of Daniel Cottier

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Among the most celebrated of nineteenth-century British decoration firms, but one that is almost completely forgotten today, was Cottier & Co., founded by the Glaswegian decorator and stained glass artist Daniel Cottier in 1869. The volume Daniel Cottier: Designer, decorator, dealer is the first comprehensive scholarly treatment of this decorator and his eponymous firm. With branches in London, New York, and Sydney, this was a remarkable international enterprise disseminating the principles of Aesthetic interior design, the movement that construed the role of art to be the provision of uplifting delight through visual beauty.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Matthew Martin reviews 'Daniel Cottier: Designer, decorator, dealer' by Petra ten-Doesschate Chu and Max Donnelly, with Andrew Montana and Suzan Veldink

- Book 1 Title: Daniel Cottier

- Book 1 Subtitle: Designer, decorator, dealer

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press, US$50 hb, 260 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/Gjqg7E

The second half of the nineteenth century in Britain saw the decoration of houses become serious business, and not just in economic terms. The industrial revolution had not only led to the multiplication of cheap, poorly designed furnishings for the home; by tempting labourers to seek work in the new factories, it also contributed to urban over-crowding, poverty, and crime. In the minds of many of the establishment, these phenomena were linked. Influenced by new social Darwinist ideas, they believed they were witnessing a degeneration of society and, with a logic which can seem puzzling from a twenty-first century perspective, the perceived decline in aesthetic standards was understood to be a symptom of this malaise. The same logic suggested that improving the taste of society at large could reverse this degeneration. In other words, art could save the world.

One result of these developments was the rise of the interior decoration firm. The home was viewed as a microcosm where aesthetic, political, and cultural values were nurtured – a beautiful home in correct taste served to shape upstanding citizens. Firms such as Morris & Co. in Britain and Herter Brothers in the United States offered their clients everything needed to realise the ‘house beautiful’.

Cottier & Co. was a part of this new artistic world. The absence of surviving company records has long hampered work on the firm and its activities. In this volume, authors draw upon a range of archival sources to inform their studies, including auction catalogues, written descriptions of decorative schemes, period photographs of interiors, and examples of the stained glass, furniture, and ceramics produced in Cottier’s workshops. The firm’s surviving painted interiors, the majority of which are to be found in Australia – including Government House in Sydney and the interiors of the former English, Scottish and Australian Chartered Bank in Melbourne – inform Andrew Montana’s essays and make this book of especial local interest. Although the artistic ‘culture wars’ of the British design reform movement can seem rather distant from colonial Australia and its very different socio-economic conditions, Cottier’s enterprise is a reminder that the wealth present in Australia in the 1870s and 1880s tied colonial society very closely to currents of contemporary taste in Britain, the country that remained the cultural touchstone for a majority of settler Australians. While Robert and Joanna Barr Smith patronised Morris & Co. in Adelaide in the 1880s, Cottier’s firm provided clients in Sydney and Melbourne with access to Aesthetic designs directly from London.

Indeed, as Chu and Montana reveal, Cottier’s firm was a major international force in the promulgation of Aestheticism – Cottier provided the cover design for the first edition of the American art critic Clarence Cook’s The House Beautiful (1878), a seminal statement on Aesthetic principles applied to the domestic interior. Chu and Veldink also provide fascinating new information on the role of Cottier as an art dealer. Although Aestheticism promoted the equality of the fine and decorative arts, the Aesthetic interior, with its carefully harmonised decorative schemes, was not always an easy environment in which to place paintings. Cottier collected and dealt in artists of the Barbizon and Hague schools, tonal painters whose work was more easily incorporated into these interiors. It was Cottier’s interest in, and promotion of, these modern Dutch painters especially that established a taste for their work in both London and New York. Intriguingly, the firm’s attempts to sell paintings to Australian clients failed. The firm’s Sydney branch, established in 1873 in partnership with fellow Glaswegian John Lamb Lyon, did, however, produce stained glass and painted decoration incorporating local flora, evidencing accommodation of local taste.

The firm’s rapid descent into oblivion in the wake of Cottier’s death in 1891 is also considered. The fall from fashion of stained glass, Cottier’s first artistic metier, likely played a role here. Stained glass was an important element in Aesthetic interiors. Where modernists would endeavour to open the house up to the outside world through plate glass windows, Aesthetic designers created self-contained interior worlds with light filtered through stained glass – the outside viewed, literally, through art. But stained glass’s association with ecclesiastical contexts contributed to the decline of the medium, and Aestheticism, in the ever more secular twentieth century.

The book is well researched and engagingly written. The only criticism that might be made of this volume is a lack of integration between the individual contributions – greater cross-referencing between essays would have resulted in a tighter overall narrative. Nevertheless, this is a major contribution to the rehabilitation of a forgotten figure and provides fascinating insights into the confluence of art, commerce, and cultural politics in the nineteenth-century Anglosphere.

Comments powered by CComment