- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Science and Technology

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Heady stuff

- Article Subtitle: A mind-bending look at evolutionary cosmology

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Paul Davies, the British physicist who brightened up the Australian science scene when he was a professor at the University of Adelaide in the 1990s, is currently director of the Beyond Center for Fundamental Concepts in Science at Arizona State University. Beyond describes itself as ‘a pioneering center devoted to confronting the really big questions of science and philosophy’. It also aims to present science publicly ‘as a key component of our culture and of significance to all humanity’, something Davies has been doing for thirty years, in popular talks, articles, and books such as About Time (1995).

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

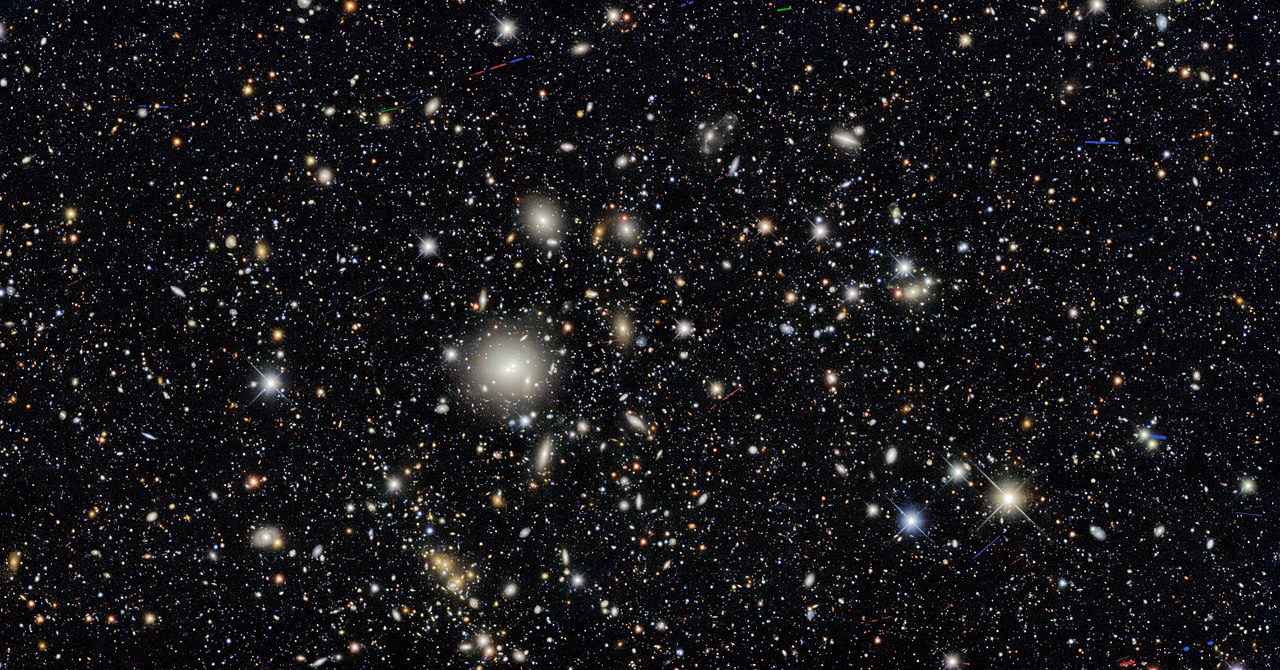

- Article Hero Image Caption: A composite image of a section of the universe taken by the Dark Energy Camera, part of an astronomical survey designed to constrain the properties of dark energy, dated May 2021 (photograph via National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): A composite image of a section of the universe taken by the Dark Energy Camera, part of an astronomical survey designed to constrain the properties of dark energy, dated May 2021 (photograph via National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Robyn Arianrhod reviews 'What’s Eating the Universe? And other cosmic questions' by Paul Davies

- Book 1 Title: What’s Eating the Universe?

- Book 1 Subtitle: And other cosmic questions

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen Lane, $35 hb, 192 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/QOeb7Y

Davies won the million-dollar Templeton Prize for Progress in Religion in 1995. The title of his bestselling The Mind of God (1992) indicates his approach, although his goal was to show that there is no inherent conflict between religion and science, and to suggest that a spiritual sense of awe comes from contemplating the universe – God’s creation if you prefer – rather than religious dogma. Interviewed for the Washington Post soon after his win, Davies said that in contrast to the post-Newtonian view of the world as ‘a gigantic collection of stupid particles colliding like cogs in a machine’ that locks human beings in its ‘cosmic juggernaut’, new scientific insights into the origin of the universe were ‘more reassuring’, suggesting a ‘grand design’ with ‘a deeper underlying meaning and purpose’.

Three decades on, at the end of What’s Eating the Universe?, Davies revisits this topic. He suggests that, although we construct meaning to enrich our lives, it doesn’t necessarily follow that the universe itself has any meaning. He speaks of understanding rather than ‘grand design’, marvelling that, ‘Somehow the universe has engineered, not just its own awareness, but its own comprehension. Mindless, blundering atoms have conspired to spawn beings who are able not merely to watch the show but to unravel the plot, to engage with the totality of the cosmos and the silent mathematical tune to which it dances.’

So, Davies says, there is a ‘stark’ choice for cosmologists: accept that the universe exists for no reason and ‘get on with the practical job of doing science’, or accept that the science rests on ‘a deeper layer of rational order’. The latter seems to be Davies’ preference. If it is right, then the ‘biggest of all the big questions discussed in this book’, he says, ‘is whether science will ever advance to the point where we can fully grasp that deeper layer’.

It’s certainly heady stuff, this cosmos of ours. People have been wondering, painting, and telling stories about it for thousands of years. Like many of us, I sometimes feel uneasy at the phenomenal cost of modern cosmological research, although this is not something Davies discusses. Perhaps it is relative – think of the coordinated, labour-intensive effort it must have taken to build Stonehenge and other ancient astronomical-ceremonial structures, including the Wurdi Youang stone circle in Wathaurong Country, Victoria. What Davies does talk about are the fruits of this modern research, and they are dazzling.

Most of us have marvelled at gorgeous pictures of nebulae and that stunning photo of Earthrise. More recently, we have seen one of the most mind-bending phenomena of all: the event horizon and shadow of a black hole. Using words rather than cameras, Davies gives an equally awesome perspective on our profligate, expanding universe, in which, he says, space itself is growing by a staggering hundred billion billion cubic light years every day. Even our own sun is enormous: ‘we now know that its core is a gigantic thermo-nuclear bomb going off at 100 billion megatons every second. The reason we’re not blown to smithereens is that the explosion is smothered by the weight of half a million kilometres of overlying gas.’

It is hard to comprehend such numbers, yet there is a prevailing view among cosmologists that ours may be just one of an infinite number of universes. Davies doesn’t think this hypothesis explains nagging questions such as when the laws of physics come into play, so there is plenty to think about in this concise story of the evolution of cosmology, even for readers familiar with the subject. Some might wish for more technical detail, such as Davies’ earlier books provided, and on some of the same topics, but here we have a handy, updated overview.

Each short chapter deals with a ‘big question’ or concept: why is it dark at night, how do we know the Big Bang happened, where is the centre of the universe (a trick question), what is dark energy, is time travel possible, can the universe come from nothing, are we alone, and much more. As for ‘what’s eating the universe’, the question arises because there’s a mysterious cold patch in the constellation Eridanus that ‘looks as if a cosmic giant has taken a huge bite out of the universe, leaving a super-void’. Trying to explain it, cosmologists have come up with apocalyptic scenarios that rival the most imaginative science fiction.

Davies’ brief discussions of his own experiences help bring the subject alive – such as hearing Stephen Hawking speak on his ‘sensational claim’ that quantum effects make black holes glow and eventually evaporate. Confounded, Davies ‘put in some arduous work’, ultimately confirming and extending Hawking’s conclusion. Then there is the ‘so-called Bunch-Davies vacuum’ and its relation to inflation theory, and Davies’ stint at Nature, trawling through submissions from readers trying to disprove Einstein’s (now amply confirmed) prediction of time-warps. Davies is modest, though, noting the many who have made bigger contributions.

His accessible book – humanised by references to historical players from Ptolemy to Einstein to Laura Mersini-Houghton – showcases a great quest for understanding; a quest that continues to uncover new wonders, and new questions, about our astonishing universe.

Comments powered by CComment