- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Law

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Questions of character

- Article Subtitle: The troubled history of Colin Manock

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

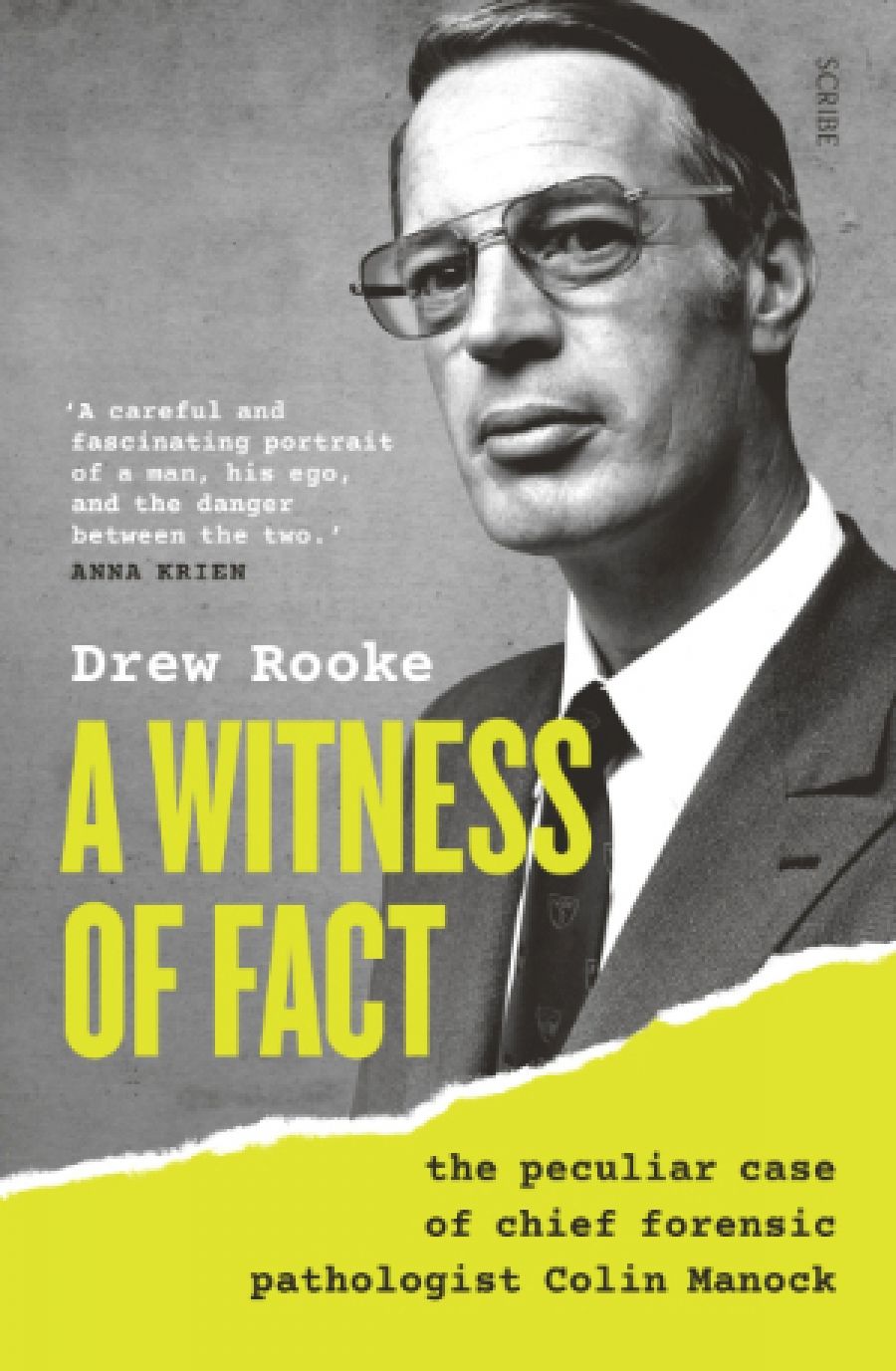

Drew Rooke begins A Witness of Fact in the viewing gallery of Adelaide’s Forensic Science Centre, his eyes scanning the stainless steel benchtops, scissors, ladles, a pair of ‘large, heavy-duty shears used for cutting through ribs’, and an arsenal of knives of different styles and sizes – ‘what you would see in a commercial kitchen’. The atmosphere is cool, sterile, and menacing. This is where disgraced forensic pathologist Colin Manock worked for thirty years. Given that this book is about Manock, the opening could be confused with scene-setting. But there is a deeper significance to the author’s choice of words, one that goes to the heart of his book: what transforms knives in a commercial kitchen into specialist tools of medical forensics?

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Alecia Simmonds reviews 'A Witness of Fact: The peculiar case of chief forensic pathologist Colin Manock' by Drew Rooke

- Book 1 Title: A Witness of Fact

- Book 1 Subtitle: The peculiar case of chief forensic pathologist Colin Manock

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $32.99 pb, 240 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/zaqevm

For anybody who has read legal academic Robert Moles’s work, there is little that is surprising in Rooke’s book. The cases that Manock botched as chief forensic pathologist and the wrongful convictions he secured have all been analysed by Moles. Rooke takes Moles’s academic research and enlivens it with lucid prose and a human dimension. He interviews judges, barristers, police officers, and litigants, and uses the tools of narrative non-fiction – thick description, a first-person narrator, and the placing of all doubts and questions on the page – to create a readable, and shocking, book. It is not, as the blurb says, ‘investigative journalism’, because the story has already been unearthed. But Rooke does well to bring the issues together and present them in a manner accessible to a wide audience.

Colin Manock served as South Australia’s chief forensic pathologist from 1968 until 1995. Untrained in histopathology, he was never formally qualified for the role, as his employers knew and later judicial inquiries discovered. Desperate to fill the position of forensic pathologist, the Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science (now known as Forensic Science SA) awarded Manock the job even though his experience comprised nothing more than basic medical training and four years’ lecturing in the University of Leeds’s Department of Forensic Medicine. Young and inexperienced, Manock arrived in Adelaide in the late 1960s to begin the work he would do for the next thirty years: conducting autopsies to diagnose the cause, timing, or manner of suspicious or unexplained deaths, and explaining his findings in court. Juries sent innocent people to jail and let the guilty walk free on the basis of his evidence.

But the story of Colin Manock is not simply one of a lack of expertise. It goes to questions of character. Manock was arrogant, lordly, and cavalier. He relished guns and murder mysteries. As a child he enjoyed dissecting animals, as an adult he preferred the company of the dead. He married several times, most recently to a dominatrix whose fetish chamber includes a mortuary table with an autopsy kit. He helped to train Dr Harold Shipman, a serial killer who murdered at least 230 of his patients. In a vocation that demanded specialist knowledge, self-abnegation, and a commitment to dispassionate, disinterested science, Manock was a showman who traded in charismatic authority. He preferred storytelling to science and seemed to regard himself as part of the prosecution. Uncertainty and impartiality were not close companions for Manock; he held fast to a version of truth clumsily cobbled together from bodies he was never qualified to take apart.

What are some examples of his ugly science? In the section entitled ‘cases’ we meet, among others, David Szach who served fourteen years in prison for allegedly killing his partner and hiding the body in a freezer where it was later found in the foetal position. Manock declared that the cooling time of a body had to be lengthened by forty per cent if it was found in the foetal position, a number that, according to the independent expert pathologists later reviewing the case, ‘had been plucked from the air’. There is the fifteen-year-old Aboriginal boy Gerald Warren who died in a racially motivated attack that involved him being beaten with a metal pipe with a threaded end and run over by a vehicle. Two men were convicted of his murder. Extraordinarily, Manock concluded that Warren had simply died after falling from a moving vehicle and that marks on his hand and face were caused by his corduroy trousers.

We also encounter Aboriginal man Derek Bromley, convicted of the murder of Stephen Docoza, who, in 1984, had been found dead in the River Torrens,; Bromley’s appeal to the High Court is proceeding as I write. Once again, Manock gave unequivocal evidence: Docoza’s death had been caused by drowning and his injuries had been inflicted before he died. On review, a forensic pathologist with special expertise in drowning stated that there was ‘no scientific basis’ for this finding and that Docoza’s immersion in water for five days meant that distinguishing between post mortem and ante mortem injuries was impossible. And there is also Henry Keogh, who successfully appealed in 1995 against his homicide conviction for the drowning of his fiancée in a bath at their home. Manock argued that Keogh had lifted her legs in the air and then pushed her head under water. Before the Medical Board and the Medical Tribunal, Manock later admitted that there was no scientific support for his opinion that the staining of her lungs suggested drowning and that there was ‘no proper basis’ for his belief that the woman was conscious while drowning, which precluded a slip and fall.

Rooke devotes his final chapter to Manock’s legacy. How could he have been allowed to practise when his incompetence was proven on so many occasions? It’s a question which takes the story out of the province of portraiture and into the realm of institutional failure. Here we might blame those working for the prosecution who unreasonably pressed for a conviction or opposed claims for wrongful conviction even when other experts revealed the inaccuracy of Manock’s opinion. We might also point our finger at the tight-knit legal fraternity in Adelaide, a small city where the legislators or judicial authorities are all too implicated in the scandal to launch the Royal Commission into Manock still urgently needed. South Australia’s former Director of Public Prosecutions, Paul Rofe QC, has defended Manock and former Attorney-General Trevor Griffin declared an Inquiry unnecessary. There is also the tendency on the part of barristers and lawyers to not mention Manock’s lack of qualifications in their appeals, negating their duty to disclose to the court. This is happening right now in the Bromley case under appeal in the High Court.

In telling this story, Rooke joins a chorus of journalists, academics, and citizens who have spent the past few decades campaigning for justice; people more committed to revealing the truth about Manock than many judicial experts. He also shows the problems of presuming a chasm between medical ‘fact’ and lay opinion. The transformation of a knife into a scalpel – its transmutation from an ordinary object into a technical instrument capable of divining the truth – is not a self-evident fact but a product of our belief in the certitudes of medical expertise and the incontrovertibility of specialist knowledge. Polite doubt, a quality so lacking in Manock, is something we might foster to remedy the harms he caused.

Comments powered by CComment