- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Her mother’s sentinel

- Article Subtitle: An unmissable filial portrait

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Another book about a mother by a daughter, I thought when I saw this one, summoning to mind Biff Ward’s In My Mother’s Hands (2014), Kate Grenville’s One Life (2015), and Nadia Wheatley’s Her Mother’s Daughter (2018). But while each of those books presents an impressive woman cramped – sometimes tragically so – by her postwar circumstances, in this case we have a subject who was nothing short of a national treasure.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

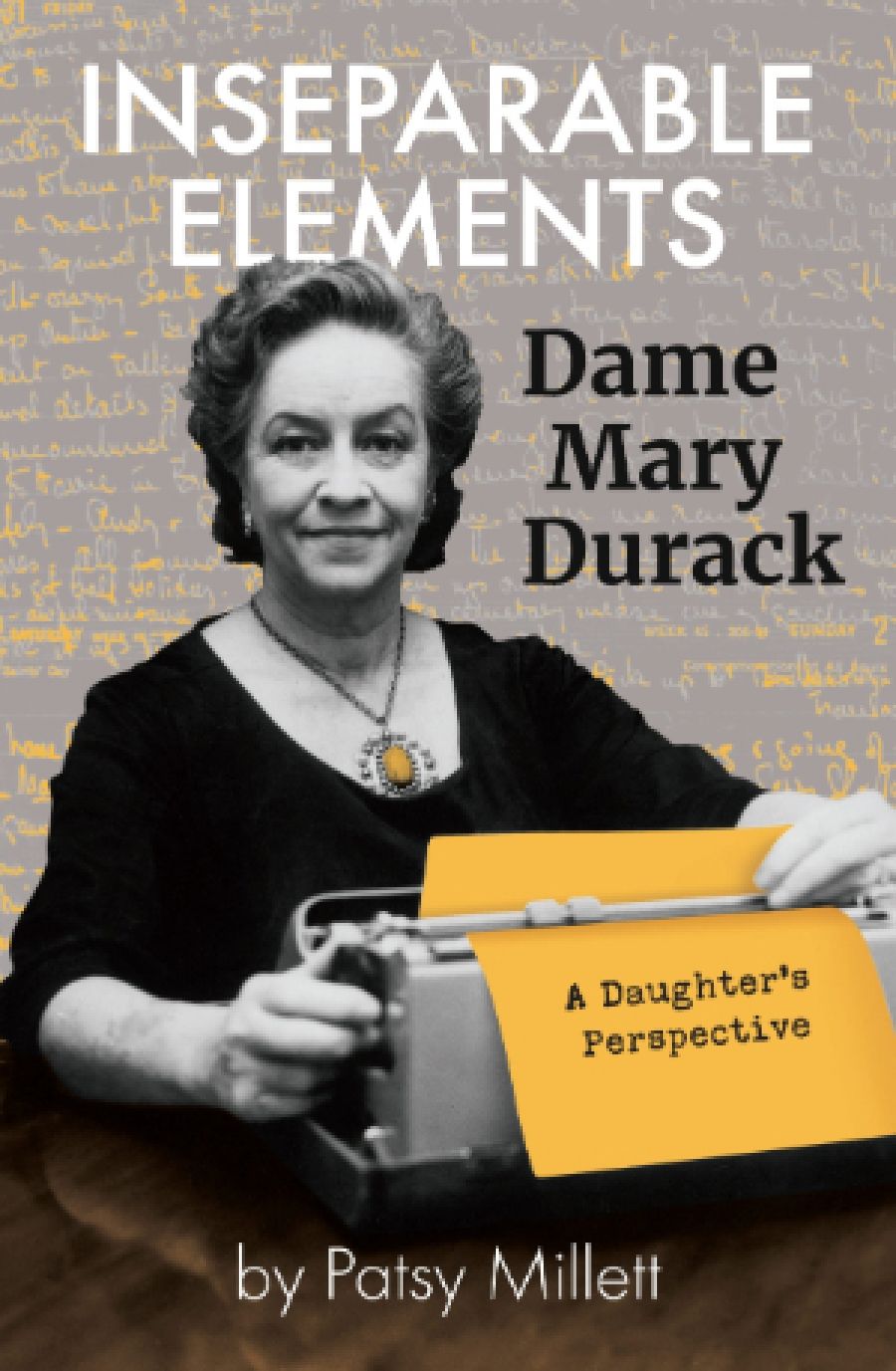

- Article Hero Image Caption: Patsy Millett, daughter of Dame Mary Durack (Fremantle Press)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Patsy Millett, daughter of Dame Mary Durack (Fremantle Press)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Susan Sheridan reviews 'Inseparable Elements: Dame Mary Durack, a daughter’s perspective' by Patsy Millett

- Book 1 Title: Inseparable Elements

- Book 1 Subtitle: Dame Mary Durack, a daughter’s perspective

- Book 1 Biblio: Fremantle Press, $34.99 pb, 464 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/6bqPQN

Mary Durack (1913–94), made a Dame of the British Empire in 1983, was well known nationally as an author and literary figure. She was prominent in numerous enterprises, such as the Aboriginal Cultural Foundation and the Stockman’s Hall of Fame. If that combination of causes sounds incongruous to today’s ears, it was not so to Durack. Her major project was the history of her immigrant Irish family’s land-taking in south-west Queensland and the Kimberley, published as Kings in Grass Castles (1959) and Sons in the Saddle (1983), a saga that fed into twentieth-century settler Australians’ hunger for a mythology of heroic pioneering, and of paternalistic relations with the First Nations peoples they displaced and dispossessed.

Throughout her life, Durack was a prolific writer – of occasional poetry, stories, plays, radio scripts, and children’s stories (illustrated by her sister Elizabeth). She published several narrative histories, including The Rock and the Sand (1969), about the Catholic missions in the Kimberley, and a novel, Keep Him My Country (1955), where, rather like Katharine Susannah Prichard’s Coonardoo (1929), the love between an Aboriginal woman and a white station owner bestows on him a spiritual bond to the land.

All this productivity took place amid a busy life of family, friends, and acquaintances, so that Durack frequently complained that she had insufficient time to devote to the writing that she saw as her vocation. Her marriage, like her own mother’s, produced a brood of children but was conducted in a somewhat semi-detached manner. Her husband, Horrie Miller, pioneer aviator of the north, spent much of his time living in Broome, while she stayed in Perth with the six children (just as her own mother had done when her husband was working on the family properties in the Kimberley, only coming to the city during the wet season).

Durack was a central figure in Perth literary life, and this book gives a vivid if rather jaundiced impression of countless parties thrown, meetings held – mostly the Fellowship of Australian Writers – and a constant stream of callers. Patsy Millett is sardonic about her mother’s sociability and her desire to nurture the literary efforts of others – not least about the nuns and priests who required Durack’s attention with their projects, most notably Bishop Jobst (avatar of the priest played by Geoffrey Rush in Bran Nue Dae). It seems that Durack could never resist a request to read a manuscript, readily reaching for her editorial blue pencil. The most famous of her protégés was Colin Johnson (Mudrooroo), with his first book, Wild Cat Falling (1965).

Durack had a number of supportive women friends, foremost among whom was the brilliant ophthalmologist Ida Mann, who shared her bush-writing retreat with Durack. Then there were Durack’s publisher and confidante, Florence James, and her cousin, the conservationist Kathleen McArthur, the pioneering outback photo-journalist Ernestine Hill, and the anthropologist Phyllis Kaberry. By contrast, her male admirers are given short shrift in this book, whether they were poor things requiring her help or badly behaved visiting writers like Hal Porter. All except for Robert Hill, Ernestine’s son, who for a while was a closer part of the family than anyone knew.

One might expect the daughter’s perspective on such a maternal paragon to be somewhat ambivalent – and Patsy Millett, Durack’s eldest daughter, does not contradict this expectation. As an adult, she saw it as her role to ‘straighten out the muddle’ of her mother’s life. She shared Durack’s belief that she never realised her potential as a writer and could have achieved much more had she been ‘more disciplined, perhaps less outgoing and more ruthless’. By her own account, Millett did her level best to encourage that necessary discipline and ruthlessness – to keep both family hangers-on and mendicant outsiders at bay. Since her mother’s death, the work on this monumental book completes the process, by documenting all the help Durack gave to those others, and the extent to which she was used by them. But Millett complicates this defensive and protective role by expressing exasperation at her mother’s uncritical generosity and characterising herself, freely and wittily, as a kind of gloomy Greek chorus, as her mother’s ‘sentinel’, she of the ‘censorious eye and caustic tongue’. Her efforts are regularly ignored.

While she expresses impatience with her mother, Millett’s attitude to her father borders on the hostile. One can read between the lines that Horrie Miller was very hard on his eldest daughter, while adoring his second, Robin, who followed in his footsteps in becoming a renowned outback pilot, and died tragically young. He was also, in his infirm old age, very ‘difficult’ and demanding of Durack, who was twenty years his junior but herself already unwell. There is macabre humour in the scenes where he is banished to ‘Sunset’, the nursing home, and plots to buy a car and effect his escape. Yet the glimpses of Horrie in quotes from his letters to Durack show him to be a dab hand with a pen, and a man of perceptive wit, albeit a monster of egotism.

Millett is hard on those who abused her mother’s generosity. Not only her father but also her aunt, the redoubtable Elizabeth, her uncle Reg, and her brother-in-law Herbert Dicks all come in for a merciless and apparently well-deserved verbal beating. The story ends in a tumult of unseemly family fighting over Durack’s papers (which included the Durack family archives). Mary’s siblings Reg and Elizabeth took legal action, and Millett accuses them of ‘hounding my mother to death’. The fight inevitably became public, attracting such headlines as ‘Author Sued for Diaries’ and ‘Dying Dame in Diaries Fight’. Millett saw it as a ‘battle over who had the right of ownership over Durack’, and in a way this book can be seen as her assertion of triumph in that battle. She had a plethora of sources: not only the family papers that her mother kept and used, but many letters and journals – all the women in the family kept journals, including Gran (Durack’s mother, Bess) until she was near ninety. Indeed, this habit was ‘a family condition, like the carpal tunnel syndrome affecting our hands’.

The book’s perspective is set by the decision to begin the story at the time of Millett’s birth, so that the first twenty-five years of her mother’s life are taken as read. For those who want to read about Mary Durack’s youth, the joint biography of the Durack sisters by Brenda Niall, True North (2012), offers a perspective entirely different – and highly recommended – from that of this unmissable daughterly one.

Comments powered by CComment