- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Sport

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Campese’s goosestep

- Article Subtitle: The Paul Keating of Australian rugby

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Australian team that won the 1991 Rugby World Cup must rank as one of our most charismatic national sport teams in modern times. The side that defeated England in the final at London’s Twickenham Stadium included several players now regarded as undisputed greats of global rugby: John Eales, Tim Horan, Jason Little, Michael Lynagh, and captain Nick Farr-Jones. There were also stirring ‘underdog’ stories: players who seemed to rise from nowhere that year to play starring roles, such as fullback Marty Roebuck and wing Rob Egerton. In Tonga-born flanker Viliami Ofahengaue, there was an early hint of the changing demographic of élite rugby players in Australia.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Barnaby Smith reviews 'Campese: The last of the dream sellers' by James Curran

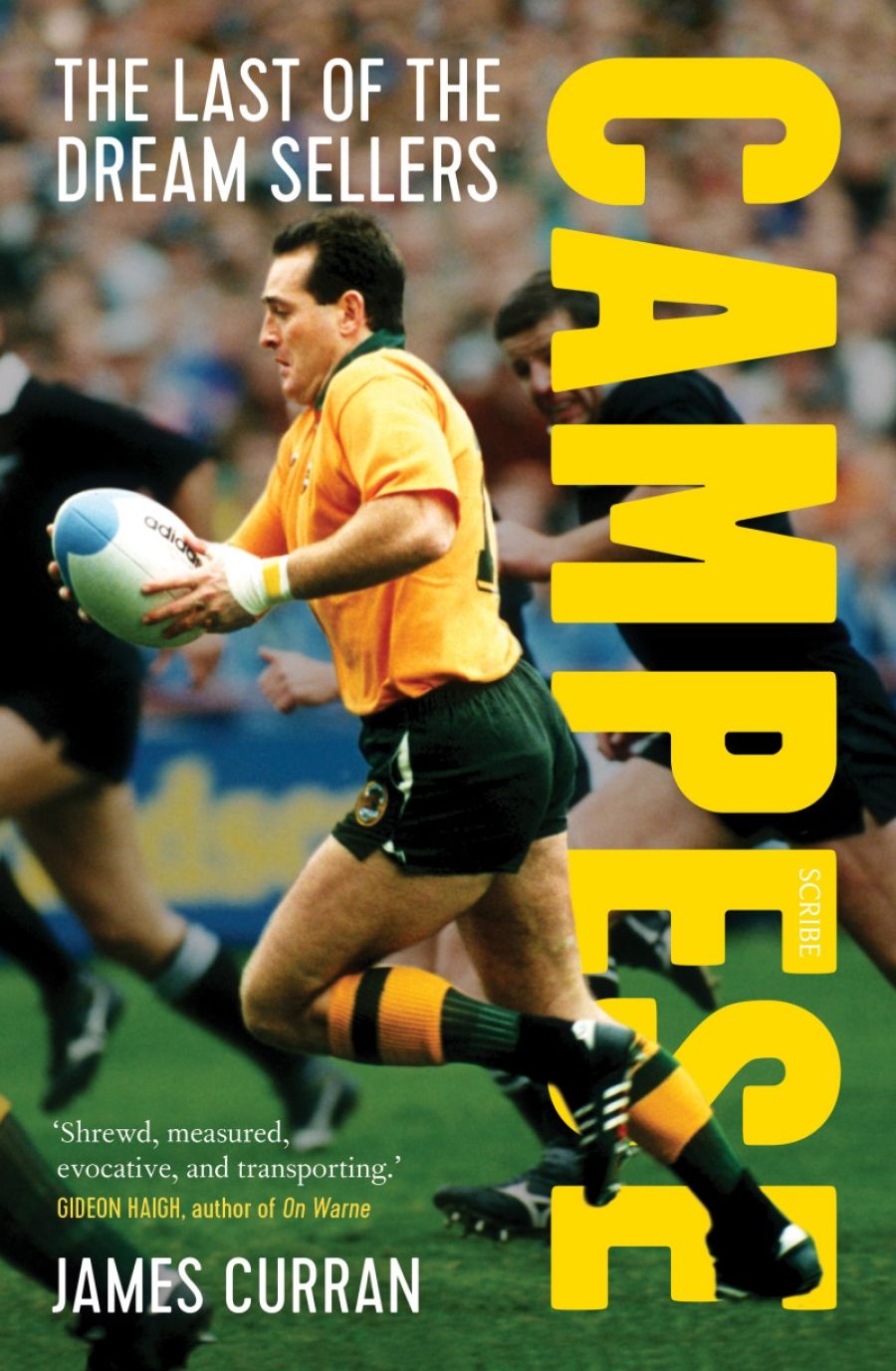

- Book 1 Title: Campese

- Book 1 Subtitle: The last of the dream sellers

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $32.99 pb, 256 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/DVBZDq

Then there was the right wing for the Wallabies. David Ian Campese, twenty-nine years old, was named Player of the Tournament and was joint top try-scorer. His exquisite performance in a semi-final against New Zealand defined that World Cup and in many ways came to define Campese’s career. His involvement in two tries – scoring one himself and laying one on for Horan – encapsulated his audacity, skill, speed, balance, and vision. It was a balletic display of athleticism and virtuosity that, for observers like James Curran, became an aesthetic experience. As Curran writes in this entertaining and enlightening book: ‘However difficult it is to describe perfectly his effect on the emotions of those who watched him, and the sheer chutzpah of his devil-take-the-hindmost attitude to playing the game, Campese’s expressiveness on the field demands critical appreciation.’

Campese: The last of the dream sellers is an intelligent and deeply felt meditation on the player’s rugby genius, as well as an erudite analysis of Campese’s complex position in the wider context of Australian sport. Curran dissects and marvels at his on-field feats, such as his famed ‘goosestep’, and addresses questions of multiculturalism (Campese’s father was an Italian migrant), class, and politics to provide a portrait of an often polarising figure who had as much ‘ability to provoke sensation off the field with his unguarded, blunt commentary ... [as] his exploits [did]on it’.

Though the book briefly covers Campese’s formative years in his hometown of Queanbeyan, this is categorically not a biography. Campese is more akin to a critical analysis, or study, of an artist’s oeuvre. The book is split into six themed chapters that are roughly chronological and that discuss different aspects of Campese’s career, which spanned 1979–1998.

Curran, a professor of modern history at Sydney University, takes a firmly literary approach to Campese as both performer and personality. The words and ideas of writers and philosophers abound: Virgil, T.S. Eliot, Hemingway, Thoreau, Shelley, Seamus Heaney, and E.M. Forster, to name a few. J.S. Bach even makes an appearance. However, many of the most beautiful quotations that Curran includes come from the great English cricket writer Neville Cardus. All these elements give Campese something in common with Gideon Haigh’s much-admired On Warne (2012). Curran alludes to Haigh on occasion. He also quotes David Foster Wallace’s famous 2006 article about tennis great Roger Federer, a work that feels like a particular inspiration for Curran. Campese might also fit into the tradition of expansive sport critique pioneered by Norman Mailer in The Fight (1975), about the 1974 heavyweight bout between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman, even if Curran’s tone is, thankfully, far gentler and more modest.

Two chapters particularly stand out for their critical acuity. The first, ‘Movement’, sets the scene in the early 1980s for Campese’s arrival on the public stage. At this time, Australian rugby was undergoing a revolution, instigated by the likes of gifted five-eighth Mark Ella, that saw the birth of the uniquely innovative, specifically Australian ‘running rugby’. Curran draws links between this daring new age in rugby and the nation’s changing political climate. The Hawke government that came to power in 1983, with its ambitious economic agenda, channelled an audacious spirit that paralleled both Campese’s play and running rugby generally. Curran writes of ‘that era’s prevailing mood – a headlong, near-carefree embrace of adventure, but adventure not without risks’. Paul Keating, especially, is seen as cut from the same cloth as Campese. Curran states that both men were ‘in their own respective ways, the carriers of this cavalier spirit’ and that ‘both were taking on establishments’.

Another key chapter is ‘Outcast’, which focuses on a calamitous error made by Campese against the touring British Lions in 1989. His errant pass late in the third test, many believe, cost Australia the game and the series. The ensuing media condemnation of Campese was brutal and, for Curran, revealing of wider prejudices. Some pundits saw an opportunity to castigate Campese for his consistently daring, risky style of play. Others blamed the error on the fact he played the Australian off-season in Italy. State rivalry reared its head as Queenslanders relished the chance to put in the boot. Even class antagonism (Campese being of working-class stock) was a factor in the vitriol. Curran astutely pulls all these things together to explore how Campese’s relationship with both the rugby establishment and the media was (and remains) fraught.

In contrast, a linguistic analysis of the British media’s adulatory reaction to Campese’s stellar performances is another of the book’s highpoints (words such as ‘beacon’ and ‘light’ dominated writing about him, Curran finds). Indeed, throughout the book there are a giddying number of quotes from press reports from across Campese’s career. If there is one criticism of Campese, it is that Curran occasionally relies on these too much. Rarely is a point made without a barrage of media quotes in support, sometimes overshadowing Curran’s own incisive analysis and considerable descriptive powers.

Ultimately, though, the book is an immense success. Unlike Campese’s on-field opponents, Curran, a historian, sociologist, and passionate rugby fan, is able to understand this quixotic sportsman.

Comments powered by CComment