- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Mexico

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: To go big is to go home

- Article Subtitle: Mexico City as palimpsest

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

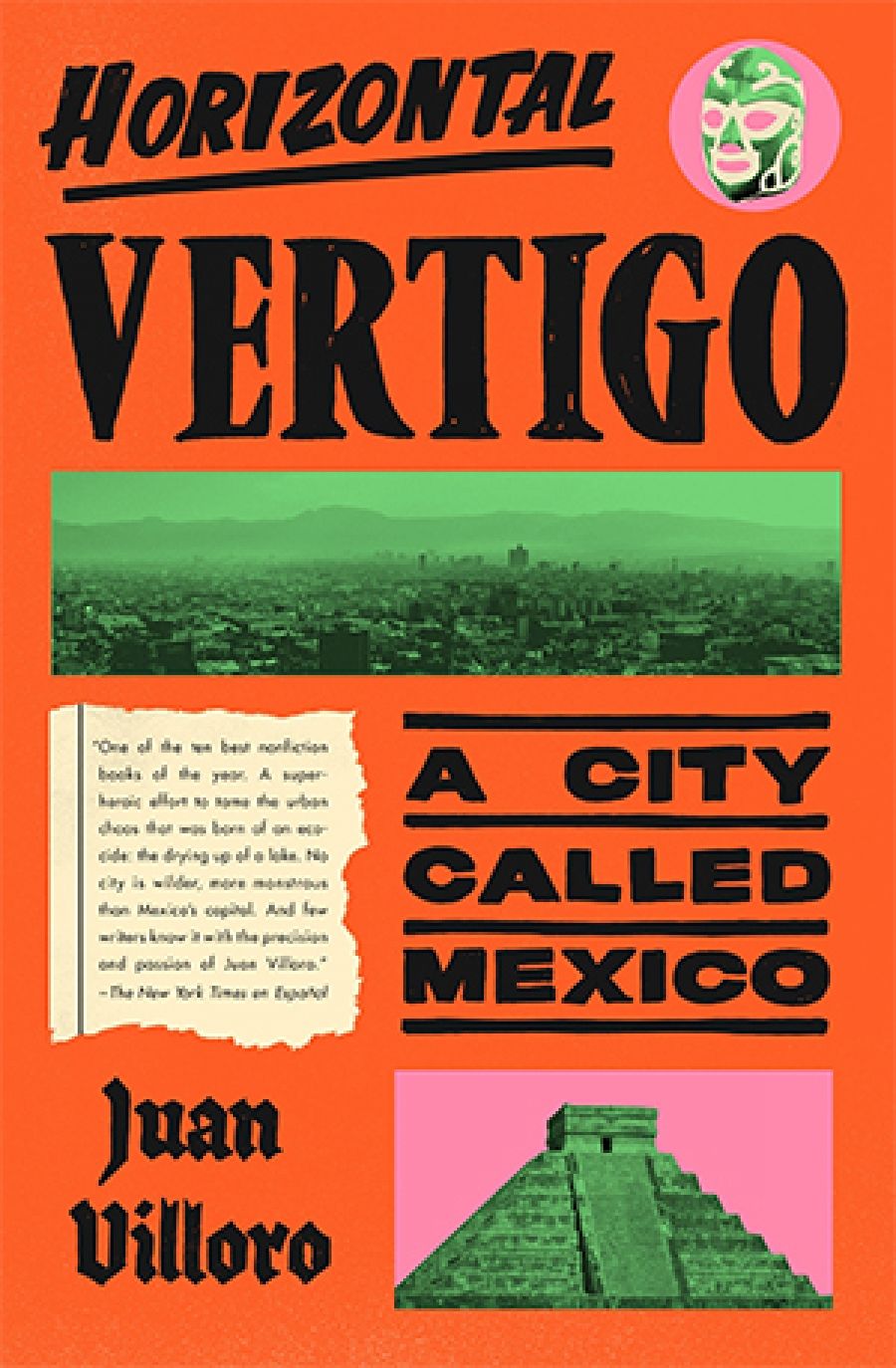

In Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series, the planet Trentor is the capital of the Galactic Empire. Seen from space, Trentor is nothing but city: there are no rivers, trees, or any other natural features, only an endless urban landscape, a metropolis that has taken over the planet. Landing in Mexico City feels like landing in Trentor: the size is overwhelming, and its apparent infinity challenges most people’s understanding of a city. Juan Villoro calls this sensation ‘horizontal vertigo’. The term is borrowed from a description of the grazing lands of the Argentine pampa, and Villoro chose it as the apt title of his chronicle of Mexico City.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Gabriel García Ochoa reviews 'Horizontal Vertigo: A city called Mexico' by Juan Villoro, translated by Alfred MacAdam

- Book 1 Title: Horizontal Vertigo

- Book 1 Subtitle: A city called Mexico

- Book 1 Biblio: Pantheon Books, $62.99 hb, 357 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/vnW9eN

Villoro was born in that very city. He is one of Mexico’s most important public intellectuals: a journalist and author of essays, novels, anthologies of short stories, and children’s books. According to him, during the almost seventy years he has lived there, the population has grown sevenfold. But how big does that make Mexico City, exactly? No one knows. Current estimates put it between twenty-three and twenty-five million people. What does it mean to live in a city whose magnitude prompts that uncertainty, a margin of error of two million people? What characteristics and social behaviours correspond to a metropolis of that size? Google Maps is operable, but is that any use when there are four hundred and twelve streets of the same name? What happens if one falls in love with someone on the other side of the city, a two- or three-hour drive away? Horizontal Vertigo explores these and many other topics with humour and insight. As a local, Villoro is the fish that questions water and wonders about its chemical composition. He takes a step back from the rat race to observe and understand the city’s oddities.

A book attempting to encapsulate the complexity of Mexico City could easily have become an encyclopedia of tedium. For all its cultural candour, Arabian Nights without Scheherazade, jinns, or erotic burlesque is just an assemblage of one thousand and one very long tales. Mercifully, Villoro knows where to draw the line. Horizontal Vertigo is a dynamic book, a collection of vignettes that includes memoir, essays, and poetry – sporadic snapshots of Villoro’s various experiences of living in the city. They don’t capture its true magnitude, but they conjure the city’s spectre, however hazily, and a sense of its enormousness. A flâneur in the style of Dickens or Baudelaire may, to a degree, be possible in present-day Manhattan or Melbourne’s CBD, but not in Mexico City. No one has taken leisurely strolls across the entire capital – it is not physically possible – but if someone did there would be no time to write about it. Villoro steers away from the trap of exactitude, and acknowledges the difficulty of tackling the city as a topic: ‘How accurate is what I’m telling? As accurate or false as the image we can have of a city where people live in millions of different ways.’

Juan Villoro (photograph via Restless Books)

Juan Villoro (photograph via Restless Books)

Villoro has spent considerable time abroad as a diplomat and academic. This brings an interesting international perspective to his writing. The vignettes in his book reference the likes of Salman Rushdie, Günter Grass, Michael Ondaatje, and André Breton. For example, in his essay ‘The City is the Sky of the Metro’, he discusses the work of the Russo-German philosopher Boris Groys, comparing the subway in Mexico City to its fabled Moscow counterpart. Villoro argues that in both cities subway stations have been ‘curated’ in certain ways in an attempt to manipulate historical narratives, a practice he attributes to ‘failed’ revolutionary movements. In a short chronicle of how the swine flu epidemic unfolded in Mexico City, Villoro plays with Harold Bloom’s idea of the anxiety of influence in authorship; the piece is titled ‘The Anxiety of Influenza’, and it discusses precisely that: the angst generated in the collectivist culture by self-isolation due to the epidemic. But one could argue that this international element of Villoro’s writing is as much a product of his time abroad as it is a reflection of Mexico City’s cosmopolitanism. Mexico City is an economic powerhouse and Latin America’s gateway to the United States; its ‘local’ identity is the cultural crucible of any megalopolis, where every faith, nationality, and background is represented.

Memory as a cultural practice features prominently in Villoro’s discussion of the cityscape. In the Anglosphere, time is a commodity, punctuality its currency. But in Mexico City, where heavy traffic makes everyone perpetually late, the currency of time is backward-looking, focusing on history as a legacy of layered memories that co-exist with the present and enrich it. This is why, for locals, the tyre shop is not incongruous in front of a colonial church, and the colonial church is not anachronic to the archaeological site that sits next to it. Villoro turns the city into a palimpsest of his personal memories and the memories of others: family, friends, and the country’s own memory of unreconciled conflict, abuse, and survival.

Alfred MacAdam is a renowned translator and scholar of Latin American literature at Columbia University (previous translations of his have been reviewed for this publication). He has produced superb translations of seminal works of Latin American literature, such as Carlos Fuentes’s The Death of Artemio Cruz. Unfortunately, his Horizontal Vertigo misses the mark. Presumably, MacAdam was trying to be faithful to the original text, to honour its Mexican identity. This approach is known as ‘foreignising’ a text (as opposed to domesticating it), and it can be very effective. In this case, the result is a frequently convoluted syntax that makes little sense, full of colloquialisms translated without much consideration for the cultural context of the target readership.

Comments powered by CComment