- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The politics of partying

- Article Subtitle: Chronicles of queer theatricality

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Wasn’t sexual expression a principal motivation of gay and queer dancefloors … Isn’t that the freedom we were fighting for? To be kinky dirty fuckers, without shame; to not sanitise ourselves in the bid for equality?’ So exhorts DJ Lanny K in 2013, reflecting on his time spinning discs at down-and-out pubs in ungentrified Surry Hills in the mid-1990s as part of Sydney’s fomenting queer subculture. Lanny K, Sydney-based Canadian immigrant, is one of a handful of artists – performance artists, dancers, even a tattooist – interviewed by Fiona McGregor in her collection of essays Buried Not Dead. Mostly written between 2013 and 2020, each essay is based on a rolling interview with an artist and draws out their recollections of early practices and careers, several united by reference to a specific time and place – Sydney’s emergent gay scene in the mid-1990s.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Sophie Knezic reviews 'Buried Not Dead' by Fiona McGregor

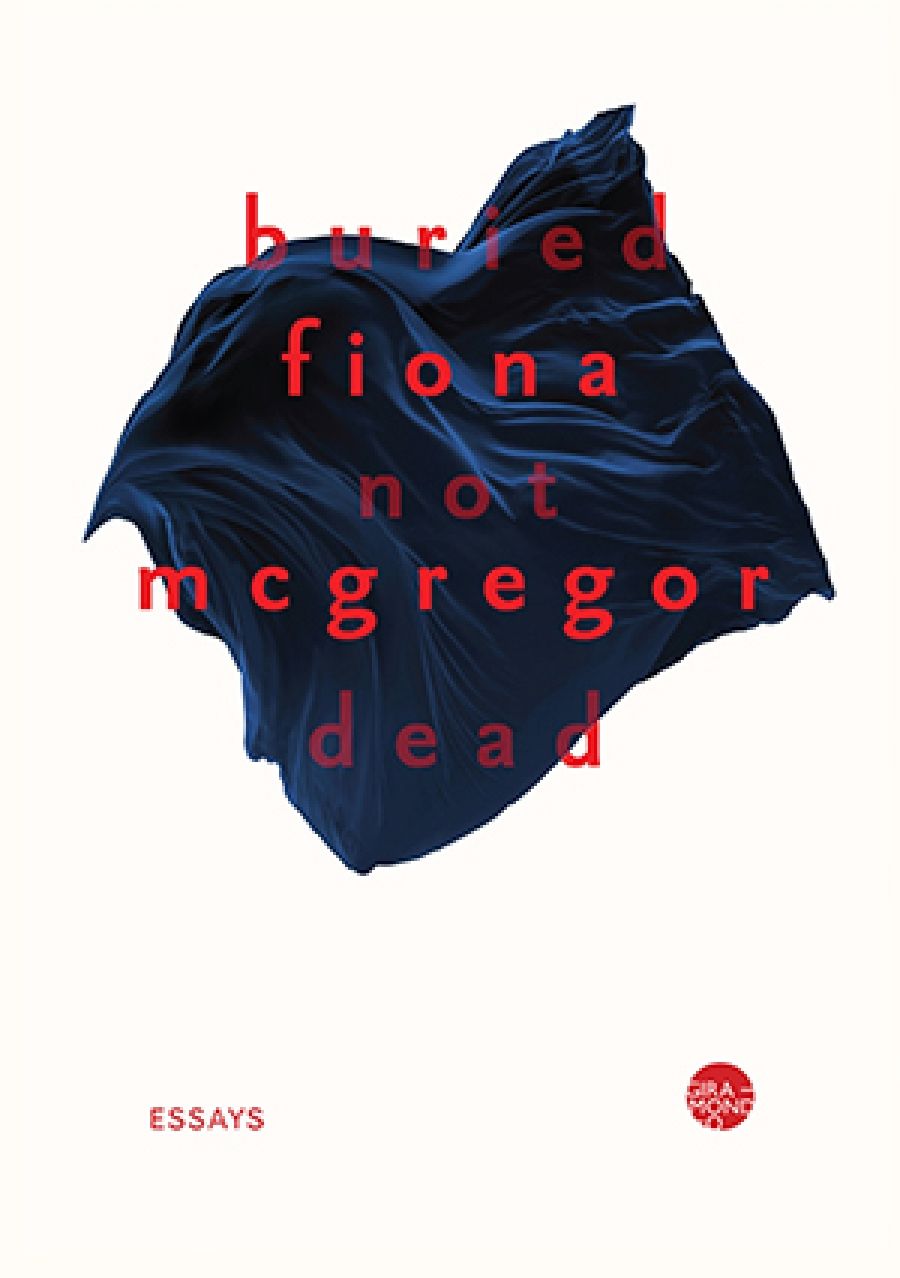

- Book 1 Title: Buried Not Dead

- Book 1 Biblio: Giramondo, $26.95 pb, 304 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/YgLvEq

The essays conjure the energy of an ascendent, vibrant subculture: a collective of individuals determined to carve out their own public sphere and flaunt their artistry – but more so to champion queer politics and community support in an era when violence against gays and dykes was ever-present: the tauntings, street bashings, and murder. Being ‘out’ is an explicit ethos running through the essays, and the second in the volume, ‘Dear Malcolm’, is penned as an open letter to former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, lambasting the conservative pragmatism of his political persona disavowing such public gay identification.

While they are styled as essays on art, the chapters reveal McGregor as a social historian, savouring the opportunity to chew the fat with her interviewees. A love of anecdotes narrated by flamboyant queers and committed artists, and of the cathartic expression of underground queer performance culture, ripples across her pages.

Most, like Lanny K, are little known beyond their subcultures or artistic circles. We meet, for example, Jiva Parthipan, a Sri Lankan dancer and choreographer emigrating from London to Sydney and coordinating community arts projects for the NSW Service for the Treatment and Rehabilitation of Torture and Trauma Survivors while waiting for his Australian residency to be secured. Eventually permitted residency through the Last Remaining Relative immigration scheme, Parthipan devises a performative lecture taking its title from the policy’s name, but the work is rejected from Parramatta’s festival of South Asian arts as it is considered ‘not Indian enough’. (It is subsequently shown at Performance Space’s Liveworks Festival in 2011.)

Two of the artists are famous: Mike Parr and Marina Abramović. McGregor follows Abramović across several exhibitions in Australia and overseas, attending Marina Abramovic Presents at the Whitworth Art Gallery at the Manchester International Arts Festival in 2009, where the iconic performance artist had curated thirteen international artists to do durational performances each day for thirteen days. Before freely wandering through the Whitworth, visitors were compelled to undergo ‘the Drill’ – ‘a series of exercises and lifestyle homilies … delivered with the zeal one might expect from the daughter of a major and a general from Tito’s Yugoslavia’, McGregor drily observes.

Australian artist Mike Parr, by contrast, comes off as a more authentic performance artist, a maverick whose work is driven by a commitment to physical trauma and risk as a form of political activism. When seventy adult asylum seekers and three children held at the Woomera immigration detention centre stitched their lips together in 2002 in a statement of political despair at their indefinite detention, Parr showed his solidarity by following suit, stitching his lips together and branding his thigh with the word ‘Alien’ in a performance titled Close the Concentration Camps (2002). As a statement against the art establishment and the commodification of art, Parr undertook a performance at the 2016 Sydney Biennale, where he torched 120 self-portrait prints worth an estimated $600,000. Yet McGregor doesn’t miss the contradictions in Parr’s work: his anti-establishment politics sitting unresolvedly with the fact that his art has been patronised by the most prestigious echelon of the very art gallery system that he denounces. Many lesser-known women performance artists gave up much earlier in their careers, McGregor notes, through lack of public and private support. ‘Gender is a huge factor.’

McGregor’s acute awareness of issues of inequity – across race, gender, and class – that operate within the art world punctuates the essays with acuity and prevents them from sliding into mere descriptive synopses. At base, though, McGregor is as much, if not more, concerned with the artist as the art. What emerges is a cast of impassioned performance artists, each vividly situated in social contexts of opportunity and obstruction. More than once I found myself scurrying to the internet to look up the unfamiliar artists McGregor chronicled. What dance projects had Parthipan been up to since McGregor interviewed him in 2013? What had become of the postwar working-class girl from Williamstown – given the moniker Cindy Ray in the 1960s as a tattoo model and tattooist – now inducted into the tattoo Hall of Fame?

While McGregor captures the energy of queer subculture – the sweaty, all-night gigs and sartorial flamboyance – her writing remains curiously unerotic. There is more frisson of desire in the first paragraph of the New York punk dyke poet Eileen Myles’s autobiographic novel Inferno (2010) than in the entirety of Buried Not Dead. Likewise, the casual references to shooting up that appear over several pages aren’t a patch on Helen Garner’s unflinching spotlight on heroin addiction in Monkey Grip (1977).

More significantly, other artist–authors have shone a brighter light on queer culture and the plight of homosexual artists in the 1980s and 1990s, a case in point being the raw incendiary rage against homophobia in the Polish–American photographer, filmmaker, and AIDS activist David Wojnarowicz’s memoirs Close to the Knives (1991) and the Waterfront Journals (1997). Similarly, a style of art writing pioneered in the last decade by American critics Chris Kraus and Maggie Nelson – whip-smart, rigorous evocations of the social and political milieu of contemporary art – knocks spots off McGregor.

But where McGregor excels is in the palpable affinity for her subjects. She is at heart a chronicler, bringing her selected artists alive in all the idiosyncrasy of their artistic passions, set against briefly sketched socio-political backdrops. Reading McGregor’s essays made me more than a little envious for an era and a subculture that so passionately flaunted its anti-establishment queerness and counter-cultural empowerment alongside a zeal for partying – a marked contrast to the killjoy context of social isolation and lockdown besetting the world over (and Melbourne in particular) in the years of Covid. Yet beneath the paean to queer performativity, the grit of McGregor’s progressive politics resounds. As she knowingly suggests, social conservatism goes hand in hand with the intolerance of difference, with homophobia and xenophobia – the true abomination against which queer theatricality protests.

Comments powered by CComment