- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Colonial haunts

- Article Subtitle: A poet’s dark self-effacement

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘The flag’s taking off for that filthy place, and our jargon’s drowning out the drums.’ A. Frances Johnson’s new collection begins with this quote from Rimbaud, which immediately betrays her appreciation for both the European avant-garde and the viral nature of the context from which it emerged. Johnson is a poet, painter, novelist, and academic acutely sensitive to such colonial haunts, perhaps largely due to the delight she takes in the other tones offered up by historical subject matter. She has displayed this previously in Eugene’s Falls (2007), an expansive novel about Eugene von Guérard, and in exhibitions dealing with the ambiguous textures of botanical empire building. Interestingly, though, her layers of historical literacy have led to a skilful inspection of her own aesthetic fetishes, writing as she does in a time when ever more bilge-water seems to be issuing from the half-drowned ship of Western culture.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Gregory Day reviews 'Save As' by A. Frances Johnson

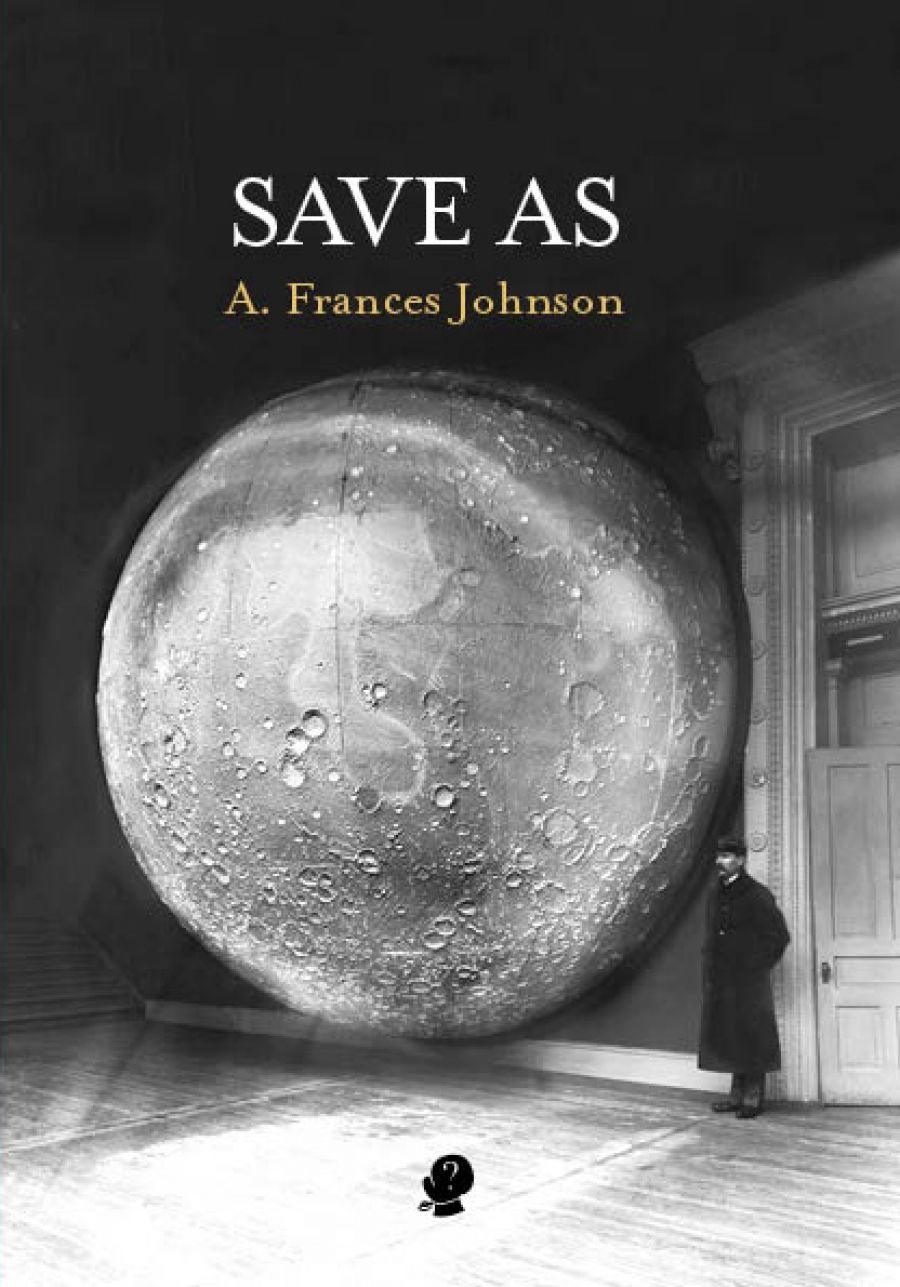

- Book 1 Title: Save As

- Book 1 Biblio: Puncher & Wattmann, $25 pb, 78 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/LPgyja

Because Johnson is both a loquacious imaginer and a hands-on maker of images, her range demands that her art must be self-reflexive, must see itself in others, and in what we are all part of. Poetry, with its licence for the slow burn of oblique remonstration, often does this best. That ‘Nature is a scene by Caspar David Friedrich’ is not lost on Johnson, nor that we have become lethal precisely because of our fantasias, our Victorian kit-edifices, our flying machines and omnivorous sequestration of landscape. Thus the need, in this era of cool-bent redemption, the era not of the coal scuttle but of the scuttle from coal, to fess up. Indeed, this is becoming our signature in part, the ratifying of artistic worth via its appetite for correction, and Johnson, as a Professor in Creative Writing specialising in ecofictions, is inevitably well positioned to know the score.

So it is that in Save As her creative and critical impulses are well and truly mashed up, the moral audit here being thoroughly threaded through the artefact. The book is divided into two halves, ‘Save Us’ and ‘Save As’. The former includes the perfect pitch of ‘My Father’s Thesaurus’, a genuinely heartrending blend of portraiture, wit, and crisp lineation that won the Peter Porter Poetry Prize in 2020. The tone of family elegies defines this first section, including ‘Ring-in’, where the poet’s grief aligns with her eye for motif on a road trip to collect her mother’s wedding rings. The tenderness of daggy memorial quests is inescapable here as the poet paints the moments – ‘My friend drives, lamb-like behind the wheel, gentle with speed limits, / a processional reprise’ – then scarifies the images she makes – ‘We find the place, a plain Besser-brick parlour / framed in doric grief, the short drive massed with orphaned / icebergs that can never know life as a true rose’. The skill of these elegies lies in their unpretentious avoidance of the pitfalls best defined by Wilde’s dictum: ‘all bad poetry springs from genuine feeling’.

In ‘Bypass Town’, Johnson observes how ‘Like us, hills are stumped / by buzz-saws we can’t see’. This is perhaps another key to her viewfinder style. One even senses that, as with Picasso, her challenge is not to muster-up ideas but to come to grips with her own inborn facility. Objects, concepts, tableaux, and ironic idioms arrive with a copiousness that must make the poet particularly aware of our human temptation to plunder. So poise becomes a quest for equidistance, le bon mot, and the balance between collection and dispersal. As in:

Love, I have come back

for a blue wren teapot, six crocheted

antimacassars, a daphne planter

and the ventricular rictus of a death

certificate, a paper chest.

This is how Johnson walks the line in this first section of the book, the line of her own need to celebrate and memorialise in forms that also guard and protect the souls departed, all of whom inhabit the living poet. That she is successful is the magic of her book, marshalling an abundant repertoire and a dark self-effacement to connect the reader to what is often highly personal material.

In the second section, ‘Save As’, poems of the lurid Anthropocene investigate the cusp of pointlessness and self-indulgence. Once again, the prismatic faculties of the poet monitor the space by assessing our inability to escape or transcend a highly mediated predicament even as we describe it. ‘Retire “I”’, she writes, ‘let it hang its head / and not conspire with / mea culpa’s last egotism’. It’s a bind we’re in, and so the poems are too. These poems of the second half are reaching for ways to depict the glare of climate and screen when sometimes perhaps only kitsch will do. They wrangle, revise, and deplore – ‘River gods self-harm as the privatised aquifer hoards’ – and at times the outrage at the neoliberal bomb on ecology is itself acerbic to the point of a too-obvious heat. We get the anger and frustration at ScoMo et al., but in diluting some of her artistry here Johnson risks simulating the issue. The fact that it took blokes a 240,000-mile trip to the Moon to look back and realise our blue planet was perfect is nevertheless a point well made.

Stay home, boil the bathwater, was Patrick White’s advice. That’s if you’ve got a home. Whatever the case, Save As reminds us that surrealism now seems not so much an art movement as a geophysical portent. Bioluminescent, garish, and at times unable to escape the automatic brief of posthuman cadence, we fail, and admit to it. That’s the point of course.

Comments powered by CComment