- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Servants’ smut

- Article Subtitle: The obsolescence of British censorship

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Censorship is to culture what war is to demography: it creates absence where presence should be. Christopher Hilliard’s fascinating and deeply informed monograph on the politics of censorship in Britain (and by extension its colonies) from the 1850s to the 1980s is concerned with the many books, magazines, and films that fell afoul of the authorities, from translations of Zola in the wake of the Obscene Publications Act 1857 to the skin mags of the 1970s.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

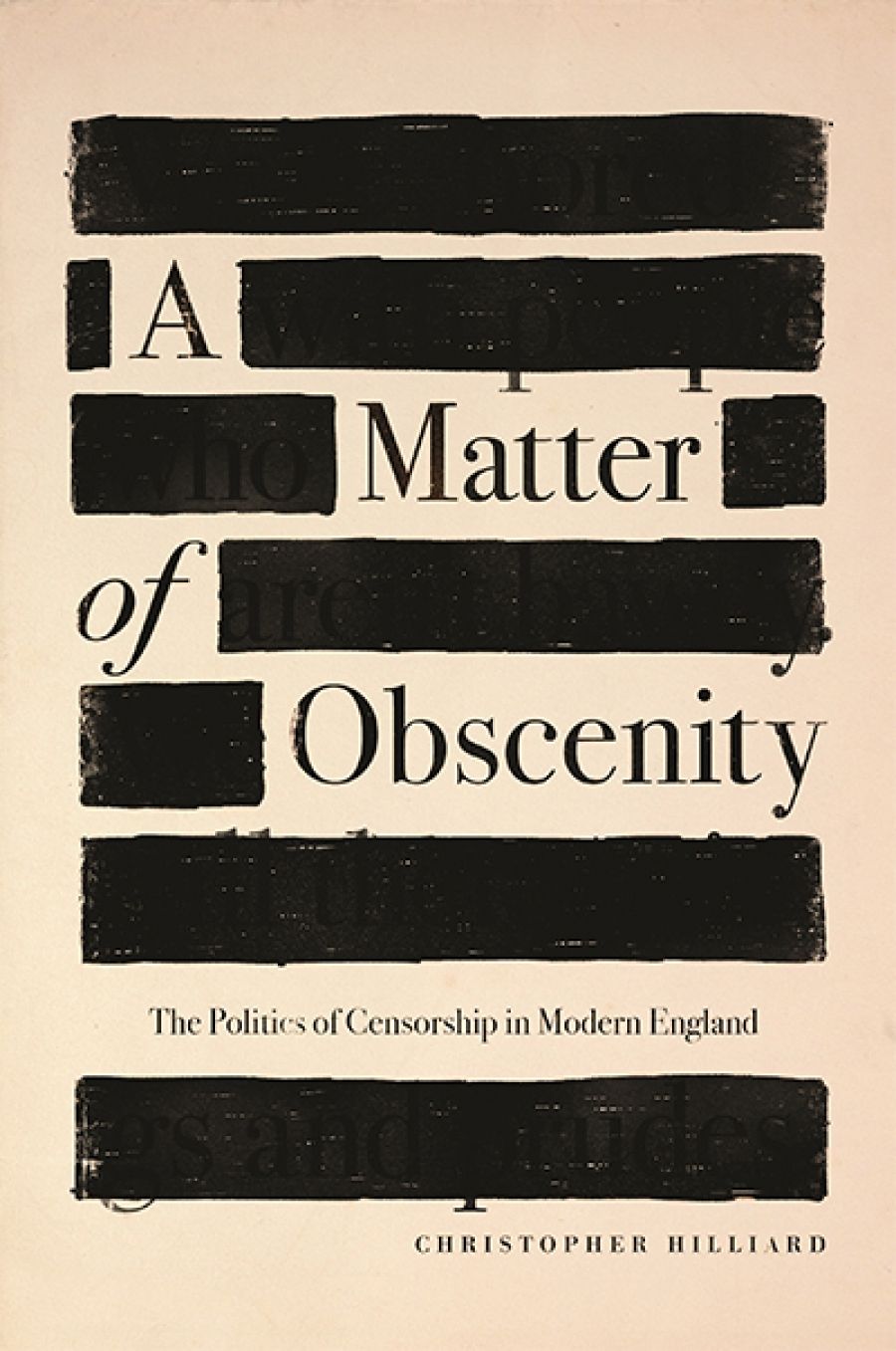

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Geordie Williamson reviews 'A Matter of Obscenity: The politics of censorship in modern England' by Christopher Hilliard

- Book 1 Title: A Matter of Obscenity

- Book 1 Subtitle: The politics of censorship in modern England

- Book 1 Biblio: Princeton University Press, $62.99 hb, 336 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/rnJQaQ

A Matter of Obscenity examines the legal and political figures who adjudicated on such matters, and attempts to distinguish the philosophical, aesthetic, moral, and commercial imperatives that shaped thinking on what the nature and scope of censorship should be. What emerges from the study is a sense that those points where the courts or official bodies intervened in matters literary were merely the visible tip of a phenomenon that ran deep. Hilliard argues that censorship in the modern era was bound up with larger anxieties about class and literacy, or nascent feminism and sexual ‘deviance’ – or even the threat that the modernist experiment posed to agreed social reality.

The effect of policing the boundaries of what is permissible in culture is, then, chilling beyond any one Lady Chatterley-like ban. Hilliard quotes Clive Bell from his 1923 polemic On British Freedom, written in the wake of the forced withdrawal from publication of D.H. Lawrence’s novel The Rainbow and the self-censorship of the nation’s powerful Circulating Libraries Association: ‘People say, “Few novels have been suppressed of late.”’ But ‘[h]ow many have never been written?’

Hilliard, a professor of history at the University of Sydney with a particular interest in the intersection of legal history and cultural production, manages the difficult feat of investing rigorous scholarly research with a lightness of tone and explanatory flair. He is aided in this by the salaciousness of much of the material under discussion, of course. More interesting still is the way he traces ‘how ideas twist across time’. He reveals, for instance, that it was the politically radical publishers of the mid-nineteenth century who evolved into the first mass-market publishers of pornography. He also shows that while anti-vice activism was largely driven by women, anti-censorship campaigners, including those fighting for the right to publish books such as Radclyffe Hall’s ground-breaking work of lesbian fiction, The Well of Loneliness (1928), were mainly men.

This shifting of social and political constellations means that it is sometimes hard to know who the goodies and baddies are. Although Hilliard evidently has little time for ‘double-barrelled bullies’ such as Mervyn Griffith-Jones – prosecutor in the Lady Chatterley trial, who famously asked jurors whether Lawrence’s novel was one you would wish ‘your wife or even your servants to read?’ – he is reluctant to draw clear lines where none exist.

Treating the question of literary merit as a means of carving out a space for licensed artistic transgression, for instance – an argument that the judge in the Radclyffe Hall trial refused to admit, despite E.M. Forster’s and Virginia Woolf’s writing on the novel’s behalf – Hilliard digs back into publishing history to show that the ‘literariness’ of a text was traditionally deployed in a manner that allowed smut to be enjoyed by the upper classes while being denied to working people. Boccaccio on vellum was permissible, under this legal and economic regime; penny dreadfuls were not.

Of course, much changed during the twentieth century. A Matter of Obscenity hinges on a shift from a patriarchal, Tory, command-and-control model of censorship that saw moral regulation as a prerequisite for civil and political order, away from deference and conformity towards a society informed by an ethos of personal autonomy – a society that (in philosopher Bernard Williams’s words) was ‘capable of supporting pluralism rather than consensus’.

The change from one to the other has been halting, piecemeal, and often downright incoherent in Hilliard’s telling. When Hubert Selby Jr’s novel Last Exit to Brooklyn (1964) faced criminal proceedings under the Obscene Publications Act, critic Al Alvarez, a witness for the defence, was moved to observe that it was the literary qualities of the book that counted against it in the eyes of a bored and uncomprehending jury. Had ‘Last Exit been more obviously what it was accused of being,’ he wrote, ‘more depraved, more corrupting … it might have stood a better chance’. But in the infamous Oz magazine case related to its ‘School Kids’ issue – an effort that now seems a quaint and earnest effort to ‘get down with the yoof’ and which Hilliard memorably describes as ‘rebellious in content but compliant in form … an unchained version of a school magazine’ – it was not the smuttiness of the material that most offended journalists and lawyers of the day, but the threat that free expression by the young apparently posed to the established order.

Hilliard concludes his book with the Thatcher years and the wane of Mary Whitehouse’s National Viewers’ and Listeners’ Association, so long a thorn in the side of the BBC. He makes the astute point that Thatcher’s social conservatism was at odds with her neoliberalism: ‘[T]he increasing power of market values ... left less space for those on the right to critique a form of immorality that was highly commercial.’

From the privileged perspective of the present, Hilliard notes, it has been some time since ‘obscenity law has been a magnet for wide-ranging discussions about society and culture’. So many other issues, from online surveillance to ‘fake news’, have pushed such discussions to the side. Those state-sanctioned and local structures put in place to protect the British public from obscenity were always designed to filter the arrival of foreign material on home soil. A Matter of Obscenity shows us that, while Brexit may have allowed Britain to ‘reclaim’ its sovereignty, the internet has rendered older efforts at cross-border moral regulation obsolete.

Comments powered by CComment