- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: More profile than courage

- Article Subtitle: Portrait of an alpha male politician

- Online Only: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Writing this review of John F. Kennedy’s formative years soon after the end of the Trump regime has evoked some surprising parallels between these two one-term American presidents (and perennial womanisers). They were both second sons born into wealthy families dominated by powerful patriarchs. Against the odds, they emerged as their fathers’ favourites and were groomed for success. Thanks not just to their wealth but to their televisual celebrity and telegenic families, they managed to eke out close election victories at a time when just enough disenchanted voters were looking for a change of direction in the White House. Despite their administrations’ profound disparities in competence and their differences in political outlook, they shared a deep distrust of senior bureaucrats and military officials, as well as an inability to work effectively with Congress. Bullets and ballots, respectively, ended Kennedy’s and Donald Trump’s presidencies, but not the cults of personality they had inspired. In the space of just over half a century, they have tilted the trajectory of American democracy and diplomacy from the tragic to the tragicomic.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Gary Werskey reviews 'JFK: Coming of age in the American century, 1917–1956' by Fredrik Logevall

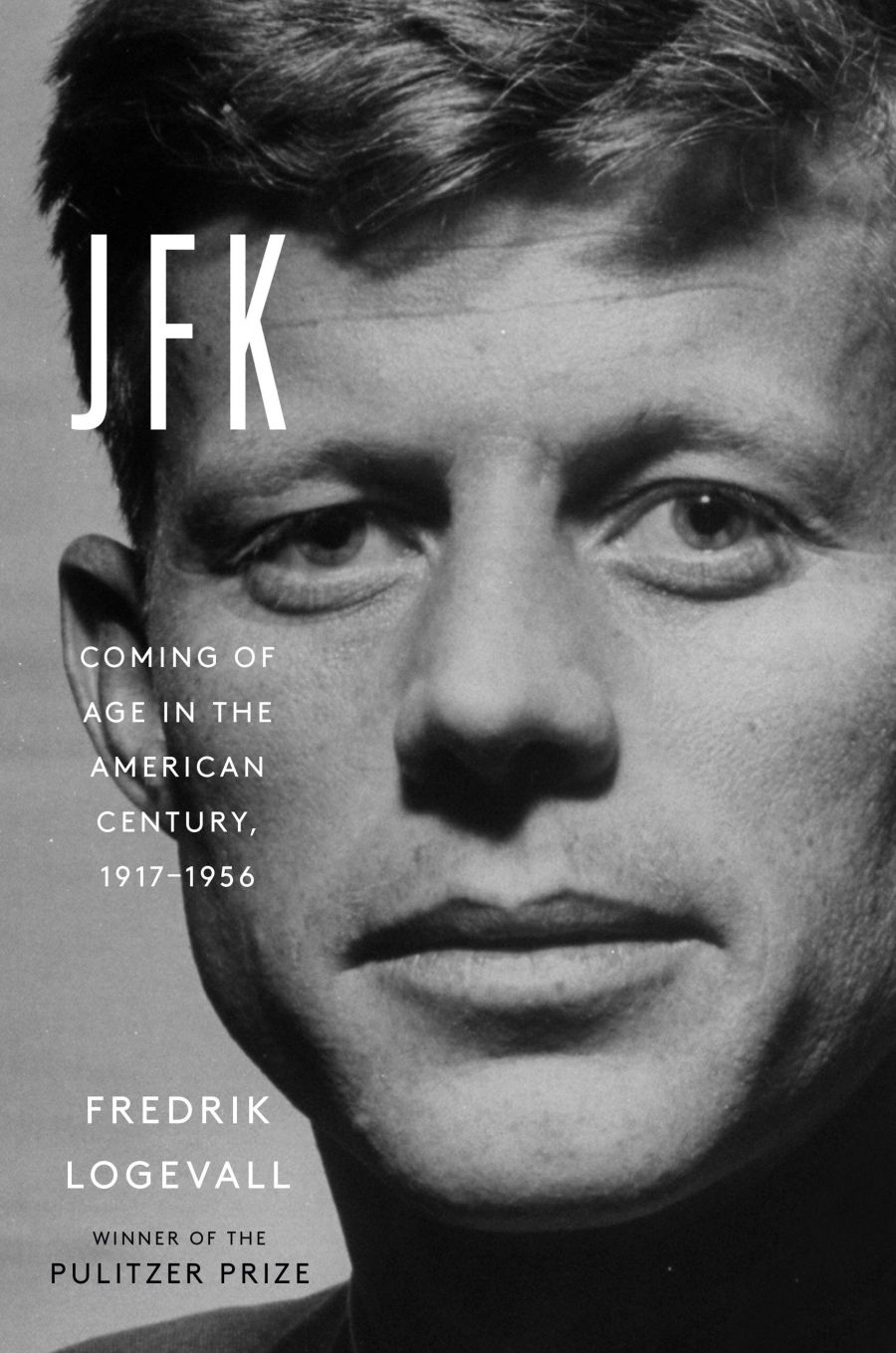

- Book 1 Title: JFK

- Book 1 Subtitle: Coming of age in the American century, 1917–1956

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $59.99 hb, 816 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/AoEgAx

The arrival of Fredrik Logevall’s widely acclaimed biography of the young Jack Kennedy (the first of two volumes) has served to reinvigorate JFK’s reputation, if only by contrast with Trump’s boorish antics. The author’s rationale for devoting 650 pages of text to ‘the years when [Kennedy’s] personality and worldview took shape’ is to help us understand the ‘seeds of his later greatness’. It was ‘through his magnetic leadership and inspirational rhetoric’, according to Logevall, that Kennedy would later elevate ‘Americans’ belief in the capacity of politics to solve big problems and speak to society’s aspirations’. More broadly, ‘perhaps it’s this abiding faith in his nation and its democratic politics that explains most fully the enduring hold of John F. Kennedy’s legacy’. This is a breathtaking assertion for Logevall to make when Trump has laid waste to America’s democratic institutions, with the support of seventy-three million of his fellow Americans.

The strength of Logevall’s well-organised, serviceably written narrative is that it is so rich in detail, thanks to his close reading of Kennedy’s private papers and the vast literature that already exists on the man and his presidency. However, although many episodes in his political and personal life are aired here for the first time, none of them will come as revelations to long-time Kennedy watchers. Logevall is the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian of the Vietnam War, so it’s not surprising that his observations about international affairs before and after World War II – and the young JFK’s responses to them – are so well judged.

Despite the richness of his material, Logevall fails to offer much in the way of social and psychological insights into the forces and experiences that shaped Kennedy’s character and personality. This would be unfamiliar terrain for any first-time biographer. But it’s also one that the author has judged to be less worthy of critical analysis than JFK’s intellectual and political formation. Tellingly, in his preface, Logevall acknowledges that Jack Kennedy was ‘heedless’ of friends and especially women, whom he regarded as ‘interchangeable’. Yet Logevall describes him on the same page as ‘a poised and discerning analyst who treated serious things seriously’. The juxtaposition of these two sentiments is jarring but probably accurate in its implied judgement that people (and love affairs) mattered far less to Kennedy than ‘serious’ affairs of state.

Logevall is also noticeably timid in his assessments of JFK’s underwhelming political record and compromised judgments as a congressman and senator between 1946 and 1956, perhaps because of his obvious underlying admiration for his subject. Then again, maybe he just felt that his narrative should ‘speak for itself’. Unfortunately, notwithstanding the reasons for the author’s reluctance to delve more deeply and critically into both the personal and political dimensions of his subject’s life, he ultimately fails to deliver on his promise to deepen our understanding of Kennedy and his future ‘greatness’. This biography literally has no conclusion.

This is such a missed opportunity. Logevall’s painstaking research fully justifies a much bolder treatment, one in which JFK could emerge as an exceptionally gifted alpha male – the best of ‘the best and the brightest’ – nurtured within a powerful crucible of wealth, class, power, and patriarchy, mixed in with the onset of what Time-Life’s founder, Henry Luce, famously dubbed the ‘American Century’. It was Jack’s immensely wealthy and driven father, Joseph P. Kennedy, who embodied and channelled all these influences into the upbringing of his four sons. (JFK’s emotionally distant mother, Rose, was relegated to the supervision of his five sisters.) Through this patriarchal division of labour, the boys learned early that they were entering a rich man’s world of masculine entitlement, one in which serial adultery would be tolerated, if not actively encouraged. This focus on male power and privilege would take a patrician turn when Joe Kennedy was appointed ambassador to the Court of St James in 1938 just six months before the Munich agreement. During this time, Jack formed lifelong friendships with and admiration for British aristocrats (his sister Kathleen, herself short-lived, was married to a future duke of Devonshire), the kind of men who treated ‘serious things seriously’ – like managing an empire – while leading thoroughly hedonistic lives.

Between the onset of war in 1939 and the 1956 Democratic convention in Chicago, Joe Kennedy worked tirelessly to support his son’s political career and personal ambitions. In summary, Joe was instrumental in: the publication of his son’s bestselling While England Slept (1940); Jack’s enlistment in the Navy, despite his many health problems; the promotion of JFK’s heroic exploits as the skipper of PT 109 through the republication of John Hersey’s New Yorker piece in Reader’s Digest; William Randolph Hearst’s assignment of Jack to cover the 1945 UN conference; bankrolling JFK’s four Congressional races, culminating in his election to the Senate in 1952; facilitating his son’s politically useful marriage to Jacqueline Bouvier, whom Jack serially betrayed before and after their betrothal; and finally signing off on JFK’s decision to run for president in 1960, following his strong showing at the Chicago convention. Without Joe’s money, influence, and drive, it’s hard to imagine that his son – however gifted – would have ever had a shot at ‘greatness’.

However, what complicates our understanding of Kennedy and renders him more appealing are his psychological vulnerabilities and lifelong medical challenges, both of which served to strengthen his emotional reserves, self-reliance, and ultimately his drive to make something of himself and the opportunities presented to him as a child of privilege. If his vaunted insouciance, realism, and lack of self-importance had been mated with a more robust set of core principles and a stronger moral compass, he might well have achieved political ‘greatness’. Instead, he turned the democratic virtue and necessity of compromise into the inveterate opportunism of a ‘total politician’ determined – as his father had taught him – to win at all costs. This led to his decision to avoid the politically risky censure of Joe McCarthy (a close family friend and a hero to many working-class Irish Catholics), while subordinating his support of civil rights to his courtship of segregationist Democrats. Soon after the publication of his Pulitzer Prize-winning Profiles in Courage in 1956 (mainly written by his uncredited staffer Ted Sorensen), more than one of his Senate colleagues could be heard saying that, in their experience, Kennedy tended to show more profile than courage.

If my compressed reading of Logevall’s admirable research is plausible, it could serve as a platform for explaining in his second volume why the achievements and failures of JFK’s ‘thousand days’ – including his deepening of America’ entanglements in Vietnam – have been so dwarfed by the legacy of ‘Camelot’ and his charisma. Ignoring his ‘heedless’ treatment of women (not least his wife), what might remain attractive for readers is that, like the equally cool Obamas, Jack and Jackie attracted artists and intellectuals to the White House. Indeed, JFK’s well-known love of poetry inspired heartfelt tributes both before and after his assassination from the likes of Auden, Brooks, Corso, Frost, Ginsberg, and many other poets.

But Kennedy’s charismatic leadership, as Gary Wills was the first to observe, also set a dangerous precedent for future presidents intent on concentrating power in the Oval Office by undermining traditional norms of governance as well as undervaluing bureaucratic memory and expertise. Donald Trump followed down a similar road, albeit more recklessly and to a much darker destination. Perhaps it’s just as well for us all that he was succeeded by the consummately uncharismatic Joe Biden, who now leads a ravaged, diminished, and hopefully chastened country in the waning days of the American Century.

Comments powered by CComment