- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Science and Technology

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Robot rules

- Article Subtitle: Unplugging the automation industry

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

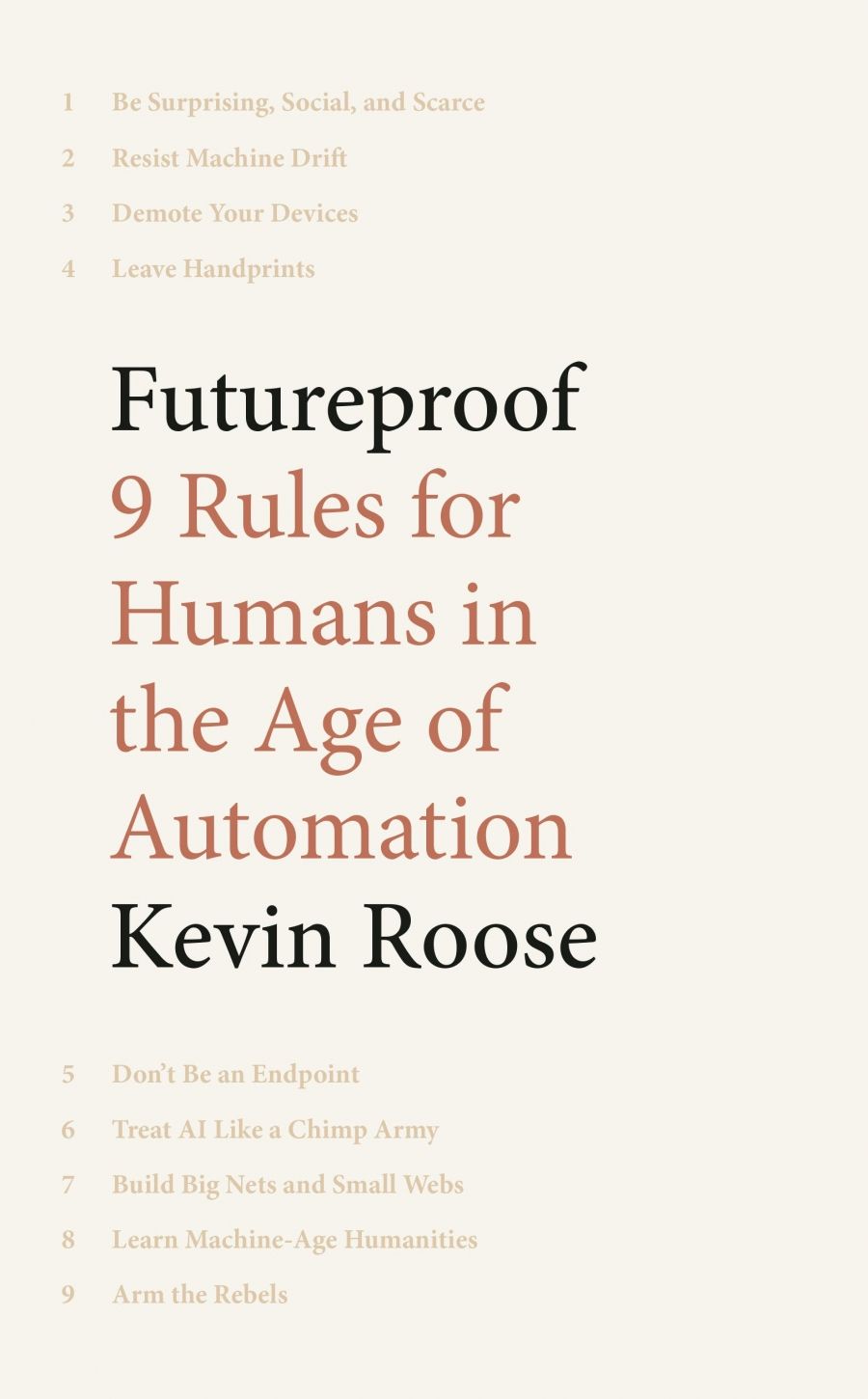

‘There is no such thing as an inherently robot-proof job,’ says Kevin Roose – a stunning admission in his new book, Futureproof: 9 rules for humans in the age of automation. We are all at risk of automation – indeed, more at risk than we think. Silicon Valley’s optimism about automation is either ‘false’ or ‘radically incomplete’. Roose says he should know: he once fell for it too.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Joshua Krook reviews 'Futureproof: 9 rules for humans in the age of automation' by Kevin Roose

- Book 1 Title: Futureproof

- Book 1 Subtitle: 9 rules for humans in the age of automation

- Book 1 Biblio: John Murray, $29.99 hb, 244 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/JrmkLe

Working as a tech columnist for The New York Times, Roose had a front-row seat at the artificial intelligence arms race. In the 2000s, he met CEOs and software engineers in slick corporate offices. They showed him tools that were going to change the world by making hospitals more efficient and communication instant, and by giving us revolutionary entertainment platforms like Netflix. These optimists kept telling him the same story: technology has historically created more jobs than it has destroyed; AI will bring great benefits to humanity; automation will improve our jobs. And how? By getting rid of the boring bits.

Roose soon discovered that everything he had been told was a lie. The first falsehood was about history. Previous periods of technological change had not improved working conditions immediately: the industrial revolution, for example, led to crippling conditions for workers in factories, with ‘long hours’ and ‘horrendous exploitation’. Farmers did not become free when they joined the assembly line; they became prisoners of technological change.

The second falsehood was to understate the risk of job losses. In fact, Roose found, no jobs were immune to automation. When asked who was at risk, people kept pointing to someone else. In a 2017 Gallup survey, seventy-four per cent of US adults thought AI would ‘eliminate more jobs than it created’, but only twenty-three per cent were worried about their own jobs. There is a famous maxim attributed to Slavoj Žižek that goes: ‘It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.’ It seems easier to imagine the end of someone else’s job than the end of your own.

The final mistake of tech optimists was to predict that AI would create better jobs. Far from getting rid of the boring parts, the tech companies simply wanted to get rid of workers. Behind closed doors, tech CEOs began to say the quiet bit out loud. Mohit Joshi, president of Infosys, a consulting firm that helps big businesses automate, said that his clients used to ask how to keep ‘maybe 95 percent’ of their workforce. Now they ask, ‘Why can’t we do it with one percent of the people we have?’ The CEO of Automation Anywhere, Mihir Shukla, proclaimed that robots ‘should take our jobs, because our jobs are wasting our human potential’. Behind closed doors he told investors a different story, that automation would get rid of workers and dramatically cut costs.

If the tech companies aim to automate jobs for the sake of profit, it is unclear what would happen to the newly unemployed workforce. One thing is apparent: we would become subject to greater and greater corporate control. The Harvard economist Richard Freeman puts it succinctly when he says, ‘Who rules the robots, rules the world.’

Futureproof claims that the solution to these dystopian threats is a set of rules, not for the robots but for humanity. This follows a similar line of thinking to other recent bestsellers, including Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life. If only we could adopt more personal responsibility, these books suggest, we could control our future. If we follow the rules, we will be saved. If we disobey them, we will get what we deserve.

Roose places the burden of gigantic economic shifts, technological change, and billion-dollar algorithmic manipulation on the shoulders of individuals. That kind of weight would crush anyone. The error is to believe that we have any agency at all. This is the ultimate gamble, for we know that the meek will not inherit the robots.

In Rules 2 and 3, Roose tells us ‘Resist Machine Drift’ and ‘Demote Your Devices’. Humans should ignore the recommendation algorithms of YouTube and Amazon, and instead make their own choices, put down their phones, and unplug their devices. These are arguments we have heard before – the question is, how? When our entire lives are built around technology, unplugging is not a realistic solution. In Rule 5, he tells us ‘Don’t Be an Endpoint’. We know that certain jobs will be automated. Roose points to Uber, Lyft, and Amazon workers, and urges them to ‘get out now’. But these workers are disproportionately from lower socio-economic backgrounds. How can they choose to not be an endpoint when their work is a matter of survival?

In Rule 8, Roose urges ‘Learn Machine-Age Humanities.’ Here, he makes a sensible case against STEM education. Politicians love telling us to learn coding and other STEM skills to prepare for the future. These skills, by nature of being static and repetitive, are in fact some of the most threatened by automation. Instead of learning STEM skills, we should learn human ones, such as being adaptable, unpredictable, chaotic, and social – things that machines cannot emulate. Instead of competing with robots on their own terrain (maths, science, and technology), we should cede ground in those subjects and pursue social, adaptable professions, such as nursing and psychology.

Far from solving our problems with technology, Roose raises more questions than he answers. One answer he does give, however, is eternally true. Instead of making ourselves more like robots, we should pursue the things that make us more human.

Comments powered by CComment