- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: An outward turn

- Article Subtitle: Comings and goings in Rapallo

- Online Only: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

How best to tell the history of literature? – a long, chronological survey tracing broad arcs of development, or as a tight focus on a single, transformative year? The dedicated study of a single writer’s life, or the story of a movement, of several writers brought together for a time by some common cause? In recent years, the history of modernist literature has enjoyed these and other treatments. In Poets and the Peacock Dinner: The literary history of a meal (2014), Lucy McDiarmid takes as her subject a single evening: a dinner, held in West Sussex on 18 January 1914, in honour of the poet Wilfrid Scawen Blunt and attended by six other poets, including W.B. Yeats and Ezra Pound. That famous evening serves to focus a wide-ranging discussion of literary friendship and romance, collaboration and rivalry.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Sean Pryor reviews 'The Poets of Rapallo: How Mussolini’s Italy shaped British, Irish, and US writers' by Lauren Arrington

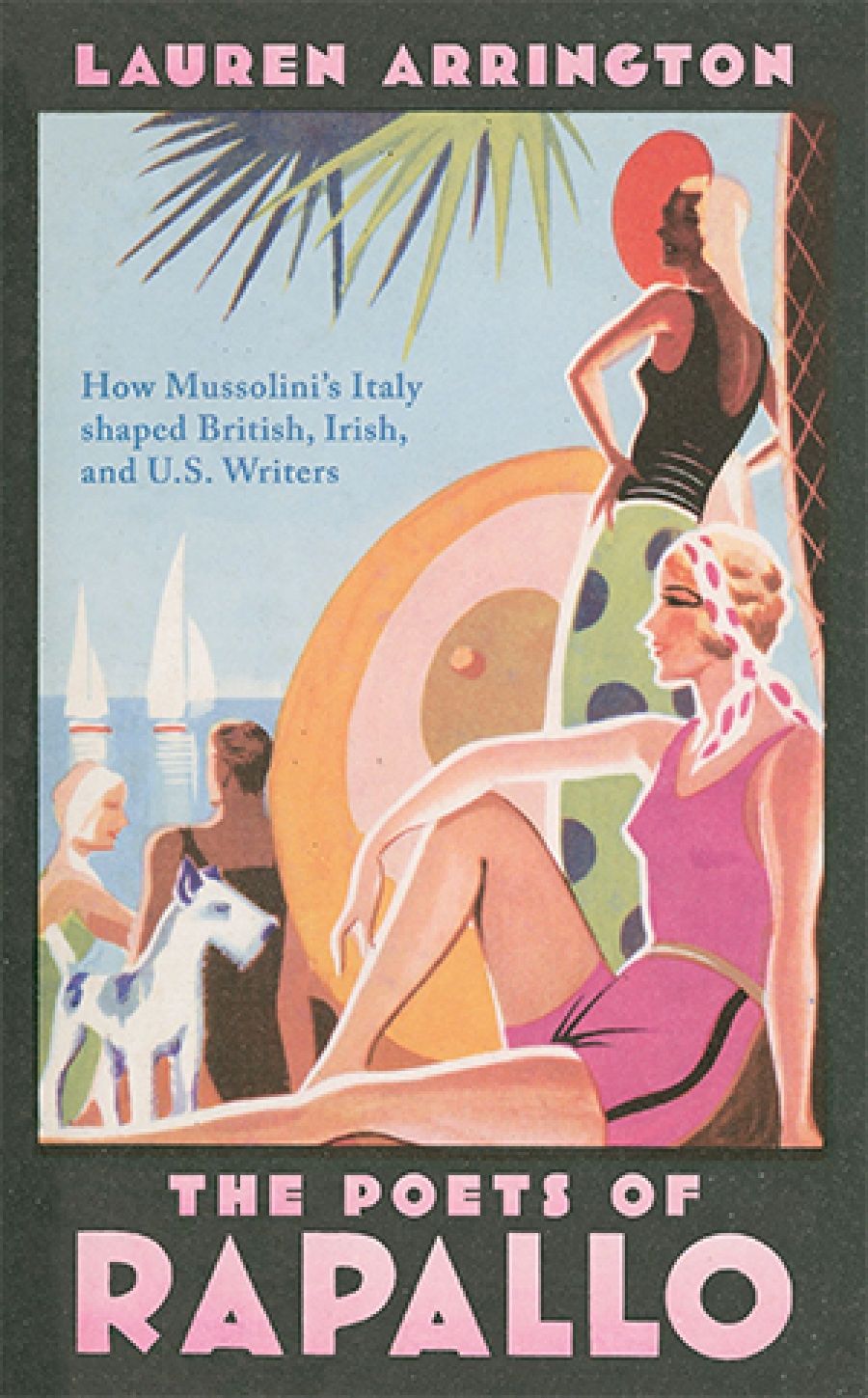

- Book 1 Title: The Poets of Rapallo

- Book 1 Subtitle: How Mussolini’s Italy shaped British, Irish, and US writers

- Book 1 Biblio: Oxford University Press, US$35 hb, 248 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/ORnGQW

Yeats and Pound are central figures in Arrington’s story. Pound moved from Paris to Rapallo with his wife, Dorothy Pound, in October 1924. Yeats and his wife, George Yeats, visited them soon after and spent extended periods there from 1928 to 1930. Basil Bunting and his wife, Marion Bunting, lived in Rapallo from 1929 to 1933. Richard Aldington, Thomas MacGreevy, Brigit Patmore, and Louis Zukofsky visited for shorter periods. Together with the coastal locale, these comings and goings make for a good backdrop: Arrington tells engaging anecdotes about Yeats composing poetry on the beach and Pound playing chess with the town’s café waiters.

But The Poets of Rapallo is concerned primarily with ideas: with conversations had over dinner, debates conducted via letters, and a diverse assortment of published and unpublished writings, from poems and plays to essays and memoirs. Although the book moves chronologically, Arrington’s chapters shuttle back and forth across the years, each exploring a specific theme, from the aftermath of World War I to the influence of Italian fascism. Arrington’s archival research is especially impressive, and the unpublished correspondence and other drafts that she has uncovered flesh out the frequently fractious relationships between her protagonists. Ultimately, what happens in this history happens in words, and sometimes it happens in Dublin or London or New York. Rapallo was but one of many nodes in a complex literary network.

Arrington’s chief aim is to show that in this period the poets of Rapallo undertook an ‘outward turn’: a newly explicit engagement with social and political problems, and in particular a shift towards right-wing politics. This picture has been clear for some time, and Arrington builds on recent and comprehensive biographies of Basil Bunting, Ezra Pound, George Yeats, and W.B. Yeats, as well as on extensive scholarship dealing with Pound, Yeats, and fascism. Still, Arrington’s focus on Rapallo is an effective and engaging device for threading these stories together.

The ‘poets of Rapallo’ were by no means a coherent movement or unified group, and they were engaged in much more than writing poetry. Yeats features here as poet, playwright, politician, editor, critic, and occult theorist. Arrington’s rewarding analyses deal with the publishing histories of little magazines and anthologies, as well as with diction and verse form. She gives as much attention to Aldington’s novel Death of a Hero (1929) as to his poetry. Moreover, Patmore, Dorothy Pound, and George Yeats were not poets at all, and one of the book’s most compelling sections details the relation between Dorothy’s paintings and drawings and the fascist aesthetics developing in Italy at this time. There are brief readings of poems by Bunting, MacGreevy, and Zukofsky, but there is surprisingly little discussion of Ezra Pound’s Cantos, despite the appearance of A Draft of XXX Cantos in 1930 and of Eleven New Cantos in 1934.

This is because The Poets of Rapallo engages ultimately with the difficult task of understanding how ideas about poetry and art were related to a right-wing politics that was frequently sexist, racist, and totalitarian. Rightly, Arrington is eager not to allow literary or aesthetic achievement to obscure or exonerate political failing, and she wants to show that, in some cases, a fascist politics actively shaped the poetics of late modernism. For Arrington, these poets’ ideas about poetry are consistent with their poetry itself, and in practice this means that those ideas are usually given interpretative priority. In a final chapter, Arrington tells the story of how, after their time in Rapallo, Aldington, Bunting, and Zukofsky struggled both to separate themselves from and to defend Yeats and Pound. In an unpublished lecture delivered in 1939, for instance, Aldington distinguishes between the Pound whom one meets in ‘real life’ and the ‘someone else’ he is ‘in his best poems’. Aldington doesn’t mean to say so, but that ‘someone else’ might in fact be more, rather than less, objectionable: what matters is the possible distinction. But it is not a distinction that concerns Arrington. Poetry is not, here, an independent form of thinking, and the poetry is thus not the reason for reading this book. The Poets of Rapallo succeeds instead as a sharp, controlled study of an influential literary network, and of shifting debates about art and politics, in a country descending into political hell.

Comments powered by CComment