- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Radical immaterialism

- Article Subtitle: The consolations of George Berkeley

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

George Berkeley (1685–1753) proposed a radical solution to the conundrums of modern philosophy. By denying the existence of matter, he dismissed the problem of how we can know a world outside our minds. Only minds and their ideas are real. The problem of understanding how mind and matter interact is dissolved by Berkeley’s immaterialism, and so is the difficulty of explaining how causation works. The source of all that we perceive, he believed, is God. Few philosophers have ever accepted this position. But the brilliance of his arguments for it earned him a place in the Western philosophical canon.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

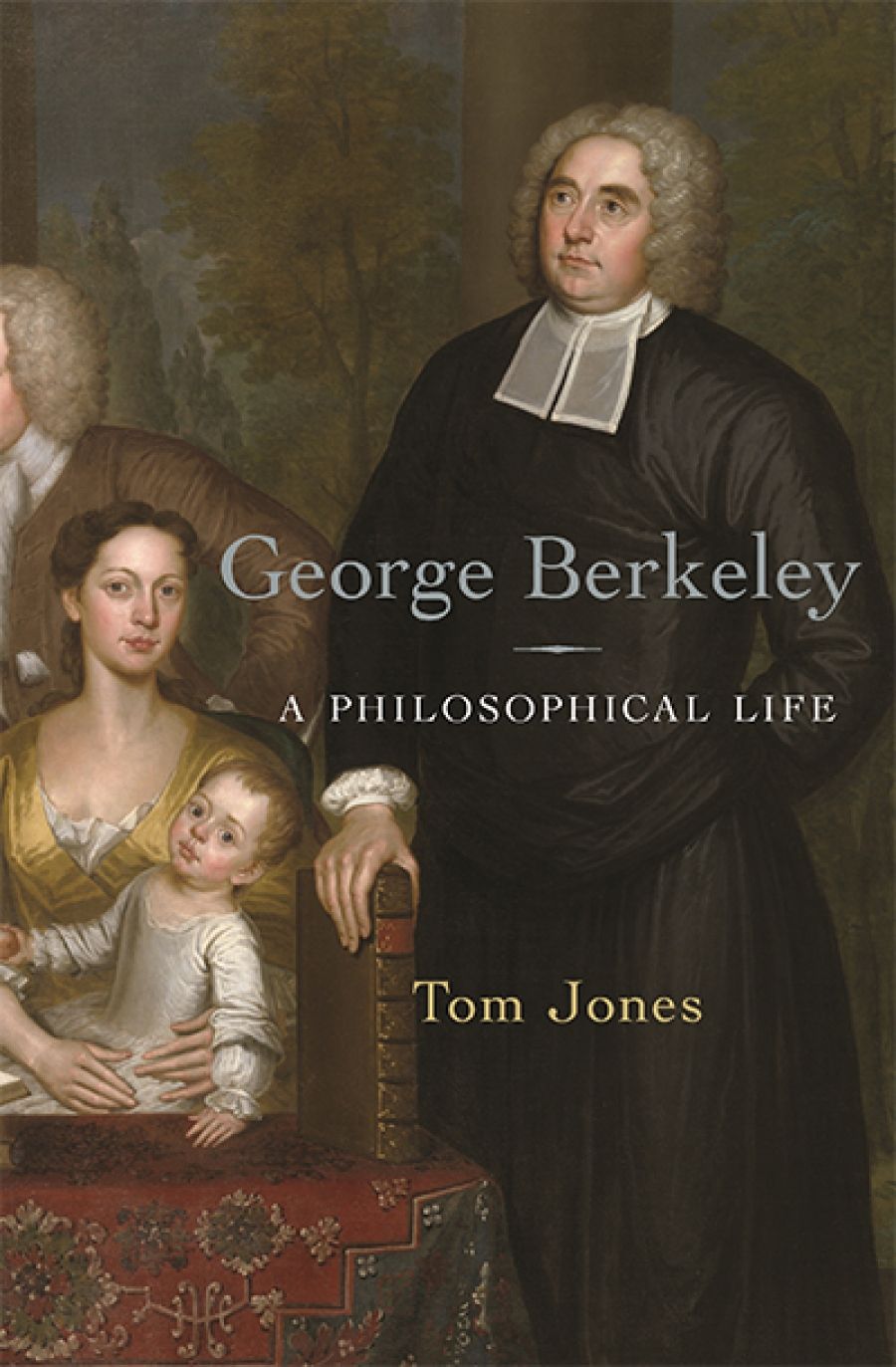

- Article Hero Image Caption: Bishop George Berkeley, painted by John Smibert (photograph via Google Art Project)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Bishop George Berkeley, painted by John Smibert (photograph via Google Art Project)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): George Berkeley

- Book 1 Title: George Berkeley

- Book 1 Subtitle: A philosophical life

- Book 1 Biblio: Princeton University Press, US$35 hb, 643 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/P0agKX

There are two ways of putting into context the work of those who made an important contribution to an intellectual tradition. The first is to explain how their ideas emerged from the work of their predecessors and influenced the thought of their successors. The second is to give an account of the role these ideas played in the life of the creator and how they served his or her purposes. In most cases, the difference is only one of emphasis. The meaning of the work for the individual and the interests of those who incorporate it into their intellectual canon coincide. Tom Jones’s biography reveals that this is not so in Berkeley’s case.

George Berkeley, the son of a government official, was educated at Trinity College Dublin, where the new ideas of René Descartes, John Locke, and Isaac Newton were part of the curriculum. Becoming a fellow of the College, he made himself known by his writings on mathematics and optics. His objection to abstractions and infinitesimal quantities, and his account of how we learn to make judgements about distant objects, put him into the empiricist camp, alongside Locke. But his main motivation for developing an immaterialist philosophy was practical and near at hand.

As a member of the Protestant élite in a country with a subject population, where civil war was an imminent threat, Berkeley always sought to promote peace and social harmony through religious teaching that regarded obedience to authority as serving the will of God. Freethinking he considered the main threat to peace, and belief in a self-sustaining physical world encouraged it. He advocated his immaterialism as a philosophy ‘directed to practise and morality by making manifest the nearness and omnipresence of God’. To most philosophers, Berkeley’s God is merely a theoretical device used to account for sense experience. For Berkeley, making people aware of God’s direct presence in their lives was the main purpose of his philosophy.

As a weapon against freethinking, Berkeley’s philosophy was a failure because he was not able to persuade people to accept it. No arguments, however cogent, could convince his readers that the material world did not exist. Some thought he was crazy to put forward such an idea. He turned, as a result, to educational and missionary projects to combat freethinking and to promote respect for authority and obedience to God.

Berkeley failed to win adherents to his philosophy. But he adhered to it himself. Throughout his life, he believed that the world presented to us by God is a form of communication which, if rightly interpreted, will guide us to appreciate and choose the good. In the mind of a mystic, this philosophy might have encouraged a belief in signs and portents. It encouraged in Berkeley a desire to learn about the world through empirical research and practical engagement.

Berkeley travelled twice to the European continent and twice to the American colonies. He immersed himself in a study of art and architecture. He interested himself in the natural environment and made a study of how people in other lands managed their civil affairs. His study of medicine persuaded him that tar water, a mixture of pine tar and water, was a cure for many ailments.

Berkeley appreciated the virtues of other ways of life, but he never deviated from a belief in the superiority of his culture and his religion. He spent many years raising money for a college in Bermuda that was supposed to convert native Americans to Protestant Christianity. When he became Bishop of Cloyne in County Cork, converting the large Catholic majority to Protestantism was one of his objectives. The native Irish, he wrote, were dirty and lazy, but they could be educated.

Jones, a reader in English at St Andrew’s University, presents Berkeley’s life through his voluminous writings, the views of his friends and family, and the opinions of those who encountered him and his writings. The result is a big book, packed with quotations from Berkeley’s works, excerpts from letters, records of journeys and activities, and details about Berkeley’s social and personal life and the people in it. Reading it requires stamina, but the reward is a better acquaintance with a man who, as the subtitle of the book indicates, lived a life under the influence of his philosophy.

Berkeley’s projects were failures. His philosophy was dismissed as a joke or the ravings of a madman. He had to give up his scheme for a college in Bermuda because he was unable to raise the necessary funds, and the native Irish remained unconverted. In his later life, he was troubled by the growth of commercial society and the vices that went with it. Freethinking, it seemed, was winning. But a reader does not get the impression from his writings or from the accounts of his friends and family that he was disappointed with the way his life had gone or despaired for the future. Perhaps he was buoyed up by a disposition that encouraged an energetic, pragmatic approach to setbacks. But his firmly held belief that he lived in the direct presence of God undoubtedly played a role. Rarely has a philosophy been so consoling.

Comments powered by CComment