- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Fully documented lives

- Article Subtitle: A daughter’s fond and intelligent book on her literary parents

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Coralie Clarke Rees and Leslie Rees are not remembered among the glamour couples of twentieth-century Australian literary life. Unlike George Johnston and Charmian Clift, Vance and Nettie Palmer, or their friends Darcy Niland and Ruth Park, neither of them wrote novels and they both spread their work across a range of genres. Critics, journalists, travel writers, children’s writers, playwrights, they devoted themselves to supporting the broad artistic culture of Australia rather than claiming its attention. Their lives were spent in juggling their literary interests with the need to make a living at a time when Australian society was even less supportive of writers than it is now. They made compromises to suburban life and the need to care for their two daughters, without ever abandoning their determination to live by the pen.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Leslie and Coralie Rees in the Blue Mountain, New South Wales, in 1956 (photograph taken by Dymphna Stella Rees)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Leslie and Coralie Rees in the Blue Mountain, New South Wales, in 1956 (photograph taken by Dymphna Stella Rees)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): A Paper Inheritance

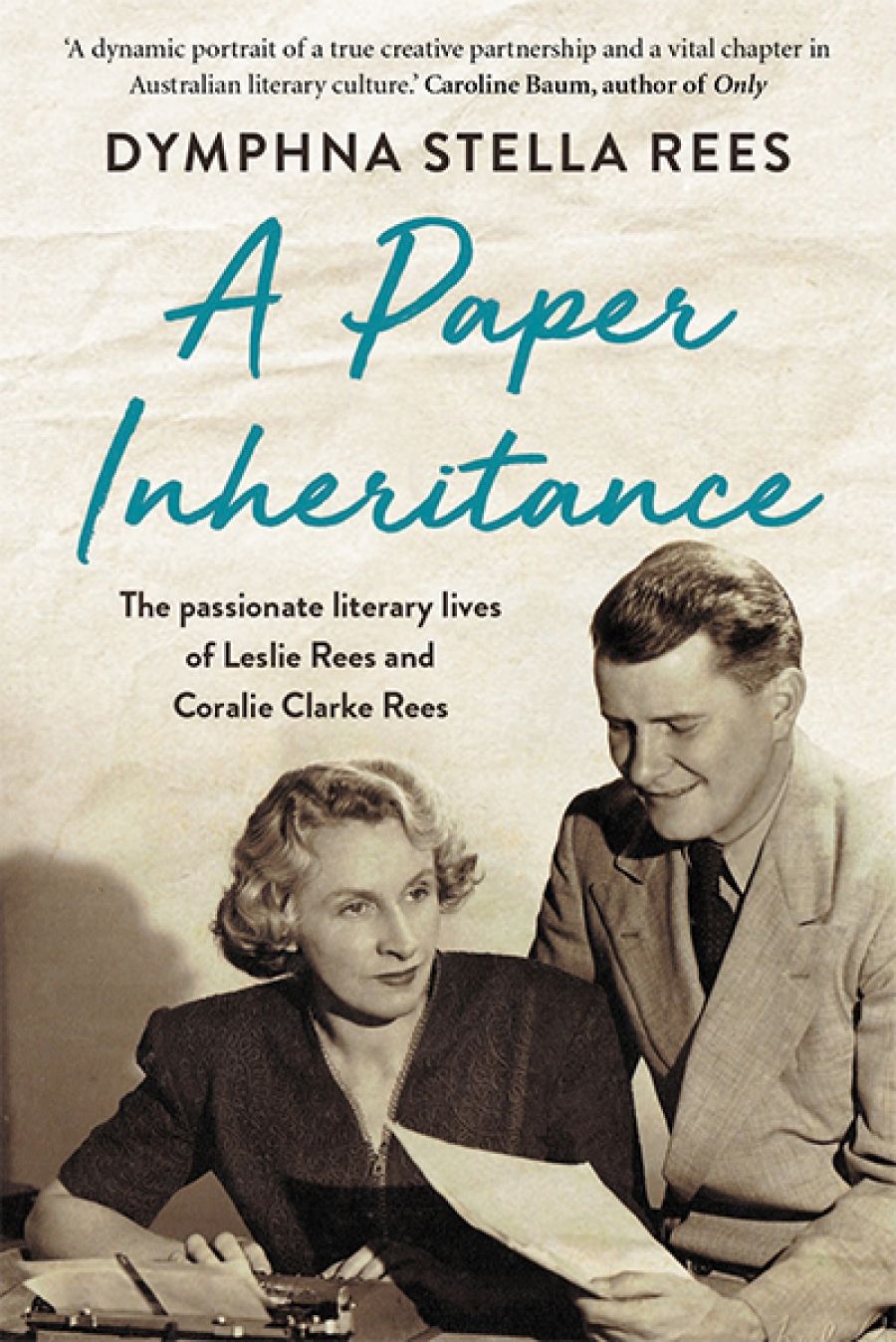

- Book 1 Title: A Paper Inheritance

- Book 1 Subtitle: The passionate literary lives of Leslie Rees and Coralie Clarke Rees

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $32.99 pb, 296 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/n1nv49

As the title of this memoir suggests, their daughter Dymphna inherited an archive of letters, drama reviews, playscripts, journalism, notebooks, and diaries covering most of the twentieth century. It would be difficult to find more fully documented lives over such a long period – Leslie lived from 1905 to 2000, Coralie from 1908 to 1972. Yet they were also disciplined writers, not given to confessional outpourings or intimate revelations. Leslie’s Hold Fast to Dreams (1982) is a rather impersonal autobiography. For most of their lives, they lived contentedly in a rented flat at Shellcove on Sydney’s inner north shore, taking turns to mind the children on weekends while labouring on their next writing projects.

Both were born in Perth, attending Perth Modern School a few years apart and meeting at the University of Western Australia. Leslie, needing to support himself as a student, worked as a journalist and drama critic for The West Australian while studying part time. The clever and beautiful Coralie was a leading lady in student productions but buckled down as editor of the Women’s Services Guild of Western Australia magazine The Dawn on graduation. In those days, the Orient line helped to fill its return ships to England by offering scholarships to young Australians for postgraduate study there. At the end of 1929, they sent Leslie to London where he could see productions of the plays he had spent so much time reading. Six months later, Coralie managed to follow him on the same scheme to study drama at the University of London.

They endured the usual struggles of Australian writers in London until, by pure luck, Leslie walked into a job as drama critic for the weekly review The Era, becoming its senior drama critic and a member of the London Critics’ Circle. Together they attended every new play and sent regular accounts of London literary life back home to Australian newspapers. Their youth and Australian enthusiasm gave them entrée into the homes of George Bernard Shaw, J.B. Priestley, Somerset Maugham, and other significant figures. They even pulled off an interview with James Joyce in Paris in 1935.

Back in Australia at the depths of the Depression, they struggled to find work. In Sydney, Leslie had to start again, freelancing for The Sydney Morning Herald, and Coralie found herself managing the temperamental Eileen Joyce’s national concert tour. With his experience of the BBC, Leslie realised that radio presented a new medium for his beloved drama; he convinced the ABC to take him on as its drama editor, setting up its drama department in 1936. He stayed there for thirty years, commissioning new Australian plays and adaptations of classics and new plays from overseas. His own play, The Sub-Editor’s Room (written in 1937, broadcast in 1956), became the first Australian play produced for ABC television. Coralie took to radio, too, writing and delivering many radio talks, now forgotten like so much of the broadcast material that helped change Australian culture.

ABC drama was Leslie’s weekday job, but he spent weekends and holidays with Coralie researching and writing travel books about Australia. The arrival of children made him aware of the dearth of Australian stories for children, and he embarked on the ‘Digit Dick’ series followed by a series about Australian native animals.

I have never encountered ‘Digit Dick’, knowing Leslie Rees’s name because of his invaluable two-volume history of Australian drama (1973, 1978), which he completed after retiring from the ABC. He was also the instigator of the Australian Playwrights’ Board that awarded a prize to a playscript each year, as a way of encouraging the production of Australian plays among the mainly amateur groups operating in the 1950s. For these things alone, he deserves to be remembered and celebrated. His history is remarkable, not only for the range of plays covered, but also for Rees’s evident familiarity with performances of most twentieth-century dramas in Australia. These volumes list and describe radio and television plays broadcast on the ABC up to 1970. Because Rees understood that radio and television drama were writers’ media, he resisted discussing film drama on the grounds that ‘film authors almost invariably play hind legs of the horse to the director or acting stars’. He was a champion of the author.

Dymphna Rees devotes little room to this achievement – indeed, it stands for itself. What she offers instead is an account of the possibilities for the writing life in mid-twentieth-century Australia. Her parents, both amazingly disciplined, committed themselves to an independent intellectual life: Coralie contributed freelance writing and broadcasting, while Leslie supplemented his ABC job with a range of publishing. Their children learnt a similar discipline, accepting that they would be farmed off to friends and relatives while their parents were away researching, and understanding that, for their parents, work came first.

Dymphna Rees, while acknowledging the feelings of abandonment she and her sister experienced as children, bears no grudges, claiming that it gave them an early self-reliance. Most of the time, she displays some of her parents’ restraint about personal matters, judiciously quoting from their letters to each other to present a picture of an orderly, loving but not especially passionate married life.

Her parents’ writings, along with her own memories, provide a social history of Australian suburban life, particularly the way families supported poorer members – the single mothers, the alcoholics, the sick – when social services were minimal. Coralie refused the role of the ‘stay at home’ wife as child-minder, cook, and cleaner, and developed various strategies to avoid them, often with the help of such relatives. She saw her role as domestic organiser, but the spinal disease that cruelly destroyed her cherished equality in the marriage was beyond her control.

This fond and intelligent book falls between biography and family memoir. Dymphna Rees, rightly assuming that her readers will have little knowledge of her parents, writes for a general audience interested in past lives, rather than the professional historians or literary researchers who may find material here. She has done her inheritance justice.

Comments powered by CComment