- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Diaries

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The ultimate star-fucker

- Article Subtitle: Agreeable hours in brothels and ballrooms

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

At a sports carnival early in Evelyn Waugh’s novel Decline and Fall, the schnockered schoolmaster Prendergast, unsteadily wielding a starting pistol, shoots poor Lord Tangent in the foot. Thereafter, Tangent barely appears in the narrative, with only a sentence now and then charting his slow medical decline. ‘Everybody else, however, was there except little Lord Tangent, whose foot was being amputated in a local nursing home.’ And later still: ‘It’s maddenin’ Tangent having died just at this time,’ some old sea dog mutters.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Henry Chips Cannon

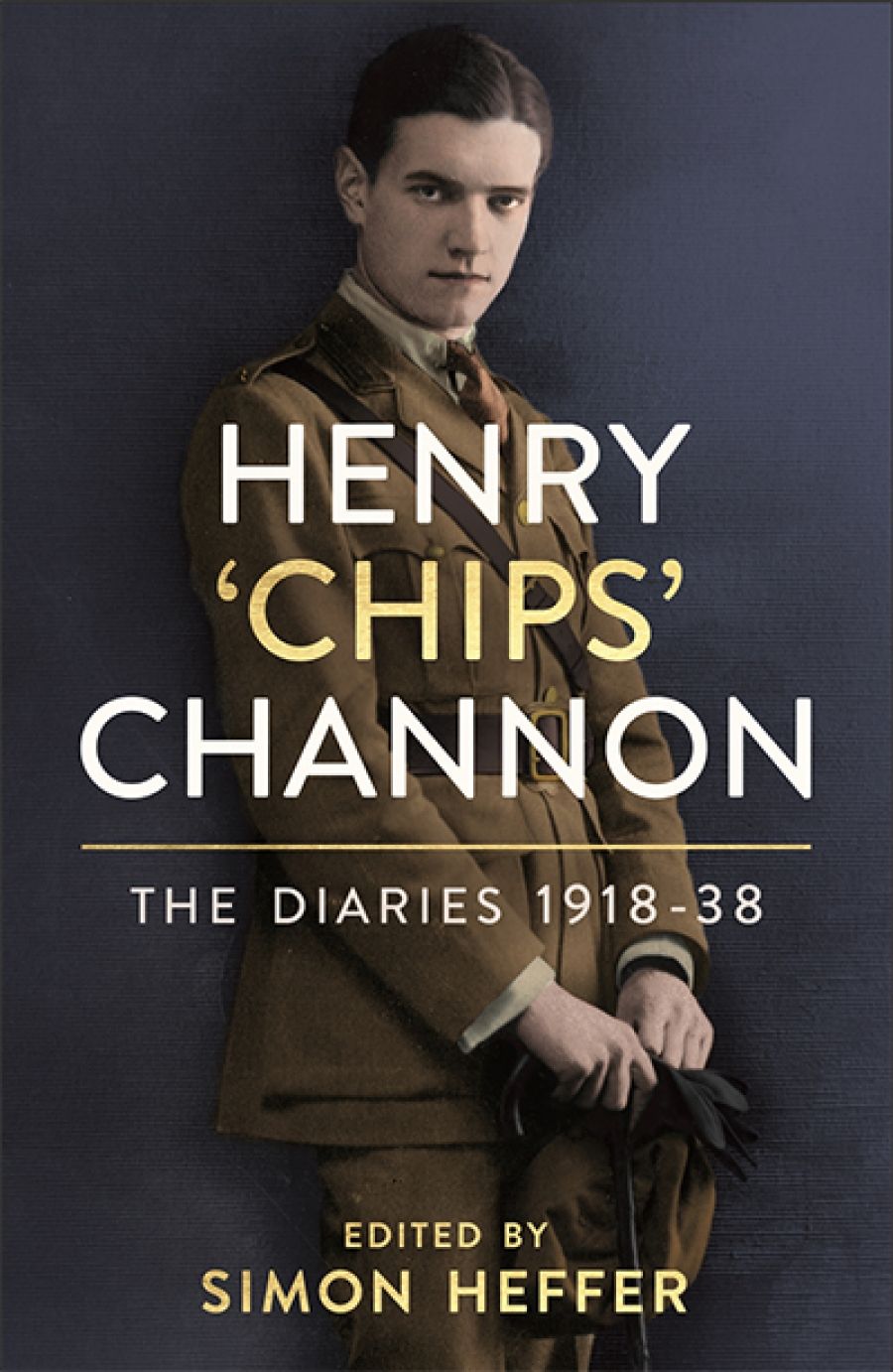

- Book 1 Title: Henry ‘Chips’ Channon

- Book 1 Subtitle: The diaries 1918–38

- Book 1 Biblio: Hutchinson, $75 hb, 1024 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/ZdrzVg

When we first encounter Henry ‘Chips’ Channon in this engrossing edition of his diaries – in Paris in early 1918, just twenty years old, working for the American Red Cross and then as an honorary attaché at the American Embassy, living all the while most comfortably off the family coin – the author is far more Waugh than Proust, whom the volume’s editor, Simon Heffer, would have him be. (A later impromptu house party in the Curzons’ closed-up London home, with the prince of Wales and champagne purloined from the Palace, is straight out of Vile Bodies.) ‘Bobbie and I lunched in the ruins of Ypres Cathedral,’ Channon writes in February 1918, a few years after its destruction. And a month later, as the Germans are gearing up for the fateful Spring Offensive: ‘My birthday. I bought myself a platinum wristwatch at Cartier’s with a cheque father had sent to me.’ Or in July 1918, the outcome of the war hanging in the balance: ‘We lunched at the Brissacs’ and in the afternoon (after an agreeable hour at a brothel) we organised a series of tea parties in our room.’

Channon grows up before our eyes, however, and smartly too. He notices more around him and manages to link people and events with ever greater clarity. The doe-eyed, sexless ingénu is soon enough something more substantial – a minor player in the celebrated milieu about which he writes with gleeful indiscretion, one eye on the person to whom he’s talking, another on whoever else has just entered the room or buttoned his flies. Thus, Proust’s ‘bloodshot eyes shone feverishly and he poured out ceaseless spite and venom about the great’, he writes after a long and boozy dinner (‘a Niagara of epigrams’), while ‘Jean Cocteau is like some faun that has indulged too long. He is a bit haggard at 26 …’ And, following the death of Antoine d’Orléans in an aeroplane accident, ‘“Toto” was the most charming if futile of men. Very inbred, his features betrayed his origin. He said he was descended from Louis XIV in twelve ways …’ These are terrific pen sketches, and the volume – the first of three – is full of them.

Quite whether you trust the sketches is another matter, one that depends entirely on whether you are willing to trade perspective for access. Channon’s politics are moneyed, establishment, and predictable, his morals pretty much the same. It’s one thing for a relative outsider to be drawn into beau monde Paris in 1918, with Prousts and Cocteaus and Steins thick on the ground and the war an exciting distant backdrop; quite another for him soon afterwards – from within the fast privilege of his adoring family and detested homeland – to plot and plan his way into English aristocratic society. So all those glamorous wartime faubourgs are quickly replaced by the great roots and tiniest shoots of England’s noble family trees, the hyphenated dramatis personae of which fairly clog up Heffer’s footnotes.

In an interview in the Guardian, Heffer describes Channon as the ‘ultimate star fucker, and if you get into that in this country, then the ultimate star to fuck must be the monarch’. Inevitably, Channon befriends fellow American Wallis Simpson and her husband the prince of Wales (‘unintellectual, uneducated and badly bred’, he writes admiringly of his friend once he is king) and, for a while at least, is their fellow traveller on all things Nazi. He doesn’t quite bed the monarch, though he is said to have done so with his handsome, beefy brother, the duke of Kent, Channon’s neighbour in Belgrave Square. His infatuation with Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon will give way to focused disdain after she becomes queen (‘She is well bred, kind, gentle and slack … She has some intelligence and reads a lot, but she is devoid of all eye, and her houses have always been banal and hideous’), yet in 1923 his adolescent amour is real enough.

In 1933 – three years before Edward succeeds George V, only to abdicate later that year (‘he fully realised that he would be a bad king in that he was convivial, unconventional, modern and impetuous and he could not stand the strain of his loneliness’) – Channon marries into the wealthy Guinness family (alas, this chapter is unrecorded in the diaries), completing his transformation. His election as a Conservative MP soon follows, and then later the knighthood and unsuccessful quest for a peerage. It could be the journey of almost any other twentieth-century Conservative MP, except that Channon writes so very well. He even manages a long affair with his landscape gardener, where mere aspirants – (Liberal) MP Jeremy Thorpe, for example – fail catastrophically while attempting the same.

For those wondering whether the slog through the quaint semi-distant past is worth it: a) it’s no slog; b) it’s not really the past. Channon’s England still exists, though there’s nothing terribly quaint about it. Alan Clark, in many ways Channon’s heir, stomped his way through this same stag hunt with great verve – the names of the families and houses pretty much the same – but this was as long ago as the 1980s and somehow with a greater sense of knowingness. Surely it was different then? Yet Sasha Swire’s recent Diary of an MP’s Wife details how little has changed – from Channon to Clark to Swire’s husband Hugo – and exactly how suffocating and unimaginative these privileged boys are when in power, which is, after all, most of the time.

Simon Heffer comes from far humbler stock, but his politics are pretty much the same – a self-satisfied and -assured belief in the decisions made by those few in the room, no matter the vacillations and consequences. (He remains an ardent Brexiteer.) His admiration for Channon comes from a wistful identification with him and his values. The wistfulness is not about a forgotten past (see above) but is, instead, a belief that the world would be a much better place if populated by even more such men. The point is hardly moot. Nevertheless, Heffer has skilfully excavated a gilt-edged mirror glass from a privileged world that ticked along Perfectly Well, Thank You Very Much, without EU regulations or research money or common markets or freedom of movement. And here we are once more. Read it through your fingers.

Comments powered by CComment