- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Philosophy

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘The world is a dark poem’

- Article Subtitle: Admitting the voices of the non-human

- Online Only: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Four kangaroos recently moved into the paddock that adjoins the house on Peramangk Country in the Adelaide Hills where I live. For weeks I had been conscious of distant gunfire, not the usual firing of the gas guns that wineries use to keep birds off their vines. I concluded that the kangaroos had been driven here by a cull. The goats, Charles and Hamlet, and the sheep, Lauren and Ingrid, who call the paddock home, seemed unperturbed by the roos’ presence. But what, I wondered, did all these animals think about one another? What, indeed, did they think about me?

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

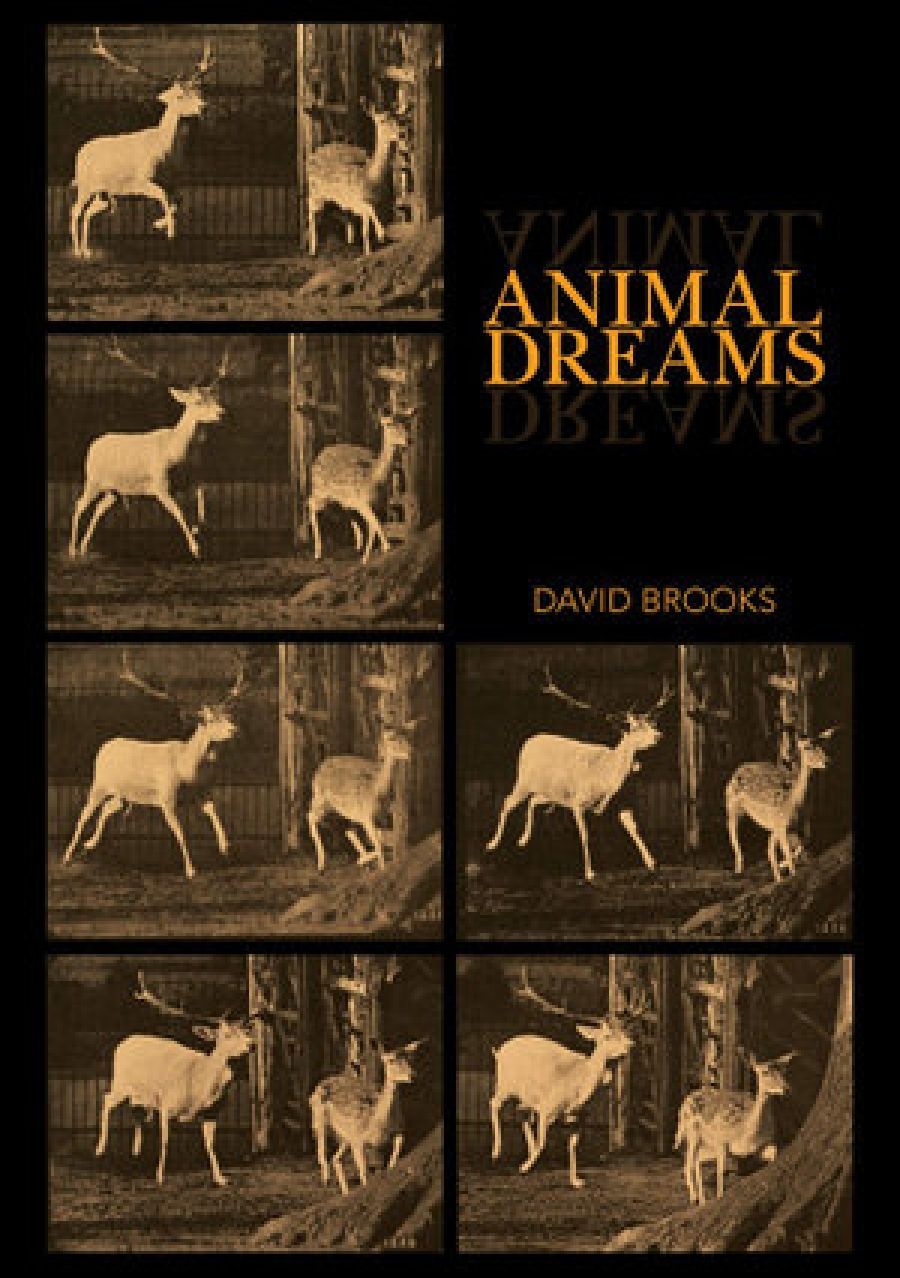

- Book 1 Title: Animal Dreams

- Book 1 Biblio: Sydney University Press, $40 pb, 290 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/QOY0r3

The culling of so-called ‘pest’ species like the kangaroo is one of many anthropocentric orthodoxies that Brooks challenges in what he calls the ‘works of undoing’ that make up this collection. Each aims to unsettle the default human-centrism that allows us to shield ourselves from the suffering of the vast numbers of animals we thoughtlessly instrumentalise. Brooks urges us to acknowledge how our indifference and cruelty interwind with their pain.

Several essays in the literary-critical mode concern what Brooks calls, borrowing from the American social psychologist Melanie Joy, Australia’s ‘essentially carnist national literature’. In a previously unpublished essay on Gillian Mears’s novel Foal’s Bread (2011), Brooks writes: ‘As in the vast majority of “fine”, “major” novels past and present, the “voice” of non-human animals in this novel is muted, and the constant suffering of which that voice might tell us therefore substantially occluded.’

Even language itself is, for Brooks, a form of conceptual violence, at once othering animals and obfuscating our essential animalness. ‘No creature is an “it”,’ Brooks declares, impugning the third-person singular neutral pronoun as ‘one of the simplest and most pervasive ways in which we distance and degrade non-human animals’. Echoing Walter Benjamin’s assertion that ‘there is no document of civilisation which is not at the same time a document of barbarism’, Brooks observes in ‘The Fallacies’ that ‘in every poem, as in almost every human artefact, there is … the trace of slaughter’.

For all the acuity with which Brooks critiques the representation of non-human animals in our national literature, there is scant discussion of recent Australian books – among them Eva Hornung’s Dog Boy (2009) and Ceridwen Dovey’s Only the Animals (2014) – that, partially at least, address his call for ‘a deep and extensive de-centring of the human’. The fact that this year’s Stella Prize shortlist included two such books – Rebecca Giggs’s Fathoms and Laura Jean McKay’s The Animals in that Country (both published, to be fair to Brooks, after the period in which these essays were written) – suggests that Australian writers may finally be allowing the ‘voices’ of the non-human to be heard.

For me, the most successful essays in this collection are those that explore Brook’s visceral and affective responses to the suffering of animals. In ‘An Exoneration’, Brooks revisits Evan Switzer’s ‘grieving kangaroo’ photographs, which went viral in 2016 and were initially purported to show a male eastern grey kangaroo cradling the head of a dead or dying doe. Brooks persuasively contests the subsequent consensus that the images had been naïvely anthropomorphised, evidencing if anything the buck’s murderous attempts to mate with the female. Reminding me of Susan Sontag’s warning about the fragility of the ethical content of photographs, Brooks’s forensic analysis of the six images – one of which strongly suggests that the doe died as a result of injuries sustained from a collision with a motor vehicle – leads him to conclude: ‘If, apart from a fair amount of logic and common human sense, we have no more concrete proof of this buck’s innocence than those who have accused him have of his guilt, it would seem to me that it is we who are left with, and must make, a moral choice.’

‘Lisika’, meanwhile, provides a harrowing account of a rescued sow as she gives birth, monitored by Brooks and his partner (as well as by a watchful brown mare), to a dozen dead piglets over the course of six days. Her refusal to eat or drink prompts Brooks to wonder if the sow has made a choice ‘to starve her unborn litter, to abort and have done with it’. When he shoos flies away from her face, Brooks detects not gratitude but ‘exhausted contempt’ in the look she gives him (pigs, in addition to being at least as intelligent as three-year-old humans, are apparently highly sensitive to outside interference).

While Derrida suggested that an insuperable ‘abyssal limit’ separates humans and animals, Brooks ponders his ‘possible commonalities of being’ with Lisika, ‘rope bridges’ that might traverse the gap between species. ‘I find these days,’ he sighs, ‘I’m losing patience with haggling over semantics in the absence of direct physical experience.’

We cannot, as Brooks reminds the reader more than once in this consistently thought-provoking collection, truly know what animals – the brown mare, Lisika, the roos, sheep, and goats in our paddock – are thinking (‘the world is a dark poem’). Yet the essays here, in their erudition and compassion, nudge us towards a more complete understanding of our non-human kinsfolk and the rich inner lives therein.

Comments powered by CComment