- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘The sun is still shining’

- Article Subtitle: Bringing A.H. Fullwood into the light

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

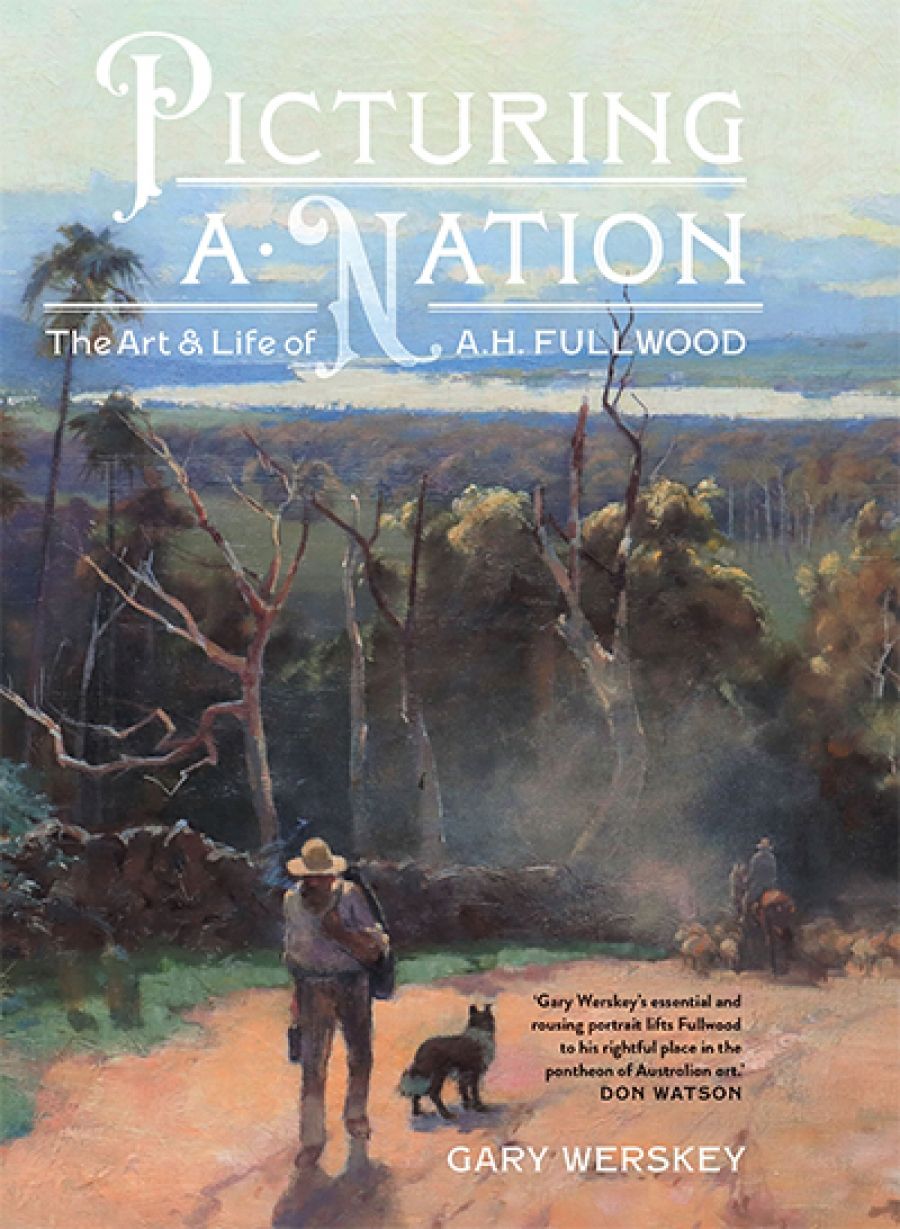

Far too few Australian artists have been the subject of comprehensive biographies. Gary Werskey mentions Humphrey McQueen’s 784-page Tom Roberts (1996) as an inspiration. Of course, there are art monographs and retrospective exhibition catalogues, but those are not life stories. With seventy-six colour plates and another fifty-one images in the text, Werskey’s thoroughly researched Picturing a Nation, set in rich historical and social context, is most welcome. As he observes, A.H. Fullwood’s life was ‘as full of pathos and plot turns as a three-volume Victorian novel’.

- Book 1 Title: Picturing a Nation

- Book 1 Subtitle: The art and life of A.H. Fullwood

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $49.99 hb, 416 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/Xx4G74

We meet English-born Albert Henry, called Jack by his family, arriving in Sydney from Birmingham late in 1883 and becoming the talented and genial storytelling ‘Uncle Remus’ to his many Australian artist friends. The nickname probably comes from his close association with the imported team of American black-and-white graphic artists and engravers working on the Picturesque Atlas of Australasia: produced in forty-two parts between 1886 and 1889 and offering a proud ‘centennial’ celebration of settler-colonial Australian history, achievements, and prospects. Fullwood’s key role in the shaping of settler-Australia’s self-image, ‘picturing a nation’ to the world through newspapers, magazines, and postcards – feeding an ‘image consumption’ arguably as influential as today’s social media – becomes even clearer in the exhibition currently at the National Library of Australia, A Nation Imagined: The Artists of the Picturesque Atlas, which is curated by Werskey with Natalie Wilson from the Art Gallery of New South Wales (until 11 July). Both the book and the exhibition admirably explain the international origins of, and the processes involved in, this mass-circulation image production.

Albert Henry Fullwood (1863–1930), c.1896 (photograph by Albie Thoms/Wikimedia Commons)

Albert Henry Fullwood (1863–1930), c.1896 (photograph by Albie Thoms/Wikimedia Commons)

Fullwood paints blossoming orchards en plein air near the Hawkesbury at Richmond with Julian Ashton and the precociously accomplished Charles Conder. He is a friend and close colleague of Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton when both move north from Melbourne in the early 1890s. He joins the bohemian Curlew Camp at Little Sirius Cove, and exhibits watercolours and oils with some success. Regrettably, many of his paintings are now untraced, but, to judge from contemporary reviews and the surviving works, he doesn’t appear to have achieved anything approaching the magisterial large-scale figure in action of Roberts’s A break away! or the colour, drama, and bravura brushwork of Streeton’s Fire’s On and ‘The purple noon’s transparent might’, which all have such timeless appeal. Werskey’s exposition of the rather toxic art politics of 1890s Sydney (continued later among the expatriate community in London) is fascinating.

Fullwood was a self-proclaimed ‘bully optimist’ – ‘I feel the sun is still shining somewhere’ – but was always in financial straits. His impoverished father had died of cirrhosis of the liver in 1883. His widowed mother, Emma, died in 1895 at sixty-three: a boarding-house servant very unlikely to be the flaming redhead portrayed in Fullwood’s beautiful Dolce far Niente of 1896 (as Werskey curiously suggests).

Perhaps that young woman is Clyda Newman, whom Fullwood married in 1896 but whose subsequent life was utterly tragic. In 1900, with no confirmed employment, he took her, their two-year-old, and their infant of six months to New York to live on a farm more than thirty miles out of town and then on to London the next year. Within months, Clyda, pregnant again, was committed to Bethlem Hospital. Inexplicably, Fullwood took off on a twelve-week trip to South Africa, followed by a spell in Windsor with Streeton. The baby died. Their eldest son died of meningitis at thirteen. Clyda suffered fifteen years in a series of asylums before she died in 1918, a ‘pauper lunatic’, while Fullwood was in France as an official Australian war artist. Werskey’s painstakingly researched and deeply empathetic account of this family’s dissolution is also important for understanding the lives of so many other dependent women and their children in those days. (More happily, and equally interesting as social history, Fullwood’s close female companion from around 1905, Frances Prudence, was clearly an adventurous and independent single mother.)

Like Streeton, George Lambert, and others, honorary lieutenant Fullwood was energised by his time on the Somme battlefields and behind the lines, writing later that ‘modern war, for all its horrible features, was magnificent pictorially’. Although the Australian War Memorial holds his two large war paintings in oil, the scheme’s administrators in London felt that his strength lay in capturing details of soldiering that were best suited to the small scale of watercolours and drawings. Werskey quotes Richard Holmes, that master biographer, on the ‘idea of finding a central but relatively neutral or unfamiliar figure to tell the story of a famous group or circle’. Holmes continues, ‘The difficulty is that the “neutral” figure usually becomes of absorbing interest in his or her own right’ – as Fullwood certainly does in Werskey’s hands. The other difficulty is the temptation to claim for that unfamiliar character too much influence in the ‘famous group or circle’, and to be combative about why he or she is less celebrated than others. Bringing someone in from the cold doesn’t mean pushing aside or discounting those already around the heater.

My one disappointment with Picturing a Nation is the confusing lack of clarity in the use of art-historical ‘labels’. Quite correctly, Werskey writes that Fullwood ‘was highly regarded by critics and peers alike as an important contributor to the movement of “Australian Impressionism”’. He says that there is continuing debate about what’s meant by the term Australian Impressionism but also ‘current consensus among scholars’ (unfortunately there’s no bibliography). Fullwood is said to have had ‘his own brand of tonal “Impressionism”’ across all the media in which he worked; to have shared Roberts’s and Streeton’s ‘“tonal realist” style and plein-air preferences’ and to have ‘cemented his relationship with Roberts and Streeton [in Sydney] at the zenith of their Heidelberg moment’. ‘Roberts’s Heidelberg’, the ‘fabled era’, and ‘the Heidelberg era’ all figure, but the origin of the now sometimes contested term ‘the Heidelberg School’ is not mentioned. Nor is John Russell, who worked with Claude Monet and whose letters from France about Impressionism Roberts showed to Streeton (and surely also to friend Remus?). Both Fullwood and Russell returned to Sydney from overseas in the 1920s and died there in 1930.

To quote Holmes again, biographers can never quite catch their subject’s fleeting figure, but Werskey’s pursuit still brings Fullwood vividly to life. He was obviously well liked, in part because he wasn’t pushy. Was he simply too poor, despite periodic successes, to maintain any substantial presence in the art world? As an ‘English/British, Australian/colonial/imperial artist’, was he too many things to be singular? Did he drink too much perhaps? We know he consulted fortune tellers.

I owe Fullwood an apology. Way back in 1985, selecting loans for the nationally touring exhibition Golden Summers: Heidelberg and beyond (we deliberately avoided the term ‘Australian Impressionism’, though we knew the power of its brand), we were unable to borrow his lovely Early Spring near Richmond, NSW, then in England, nor the charming Hop Pickers, New Norfolk, Tasmania (1893), which is still in the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. We therefore represented him with Sturt Street, Ballarat, the black-and-white illustration Werskey calls his ‘most acclaimed contribution to the Atlas’. I knew his nineteenth-century reputation called for more. And he deserves more now than the single painting in the National Gallery of Victoria’s She-Oak and Sunlight: Australian Impressionism (until 22 August). I hope that Gary Werskey’s efforts, and a planned retrospective at Macquarie University in November, bring more of his missing pictures to light.

Comments powered by CComment