- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Balancing act

- Article Subtitle: A forgotten pioneer of aviation

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

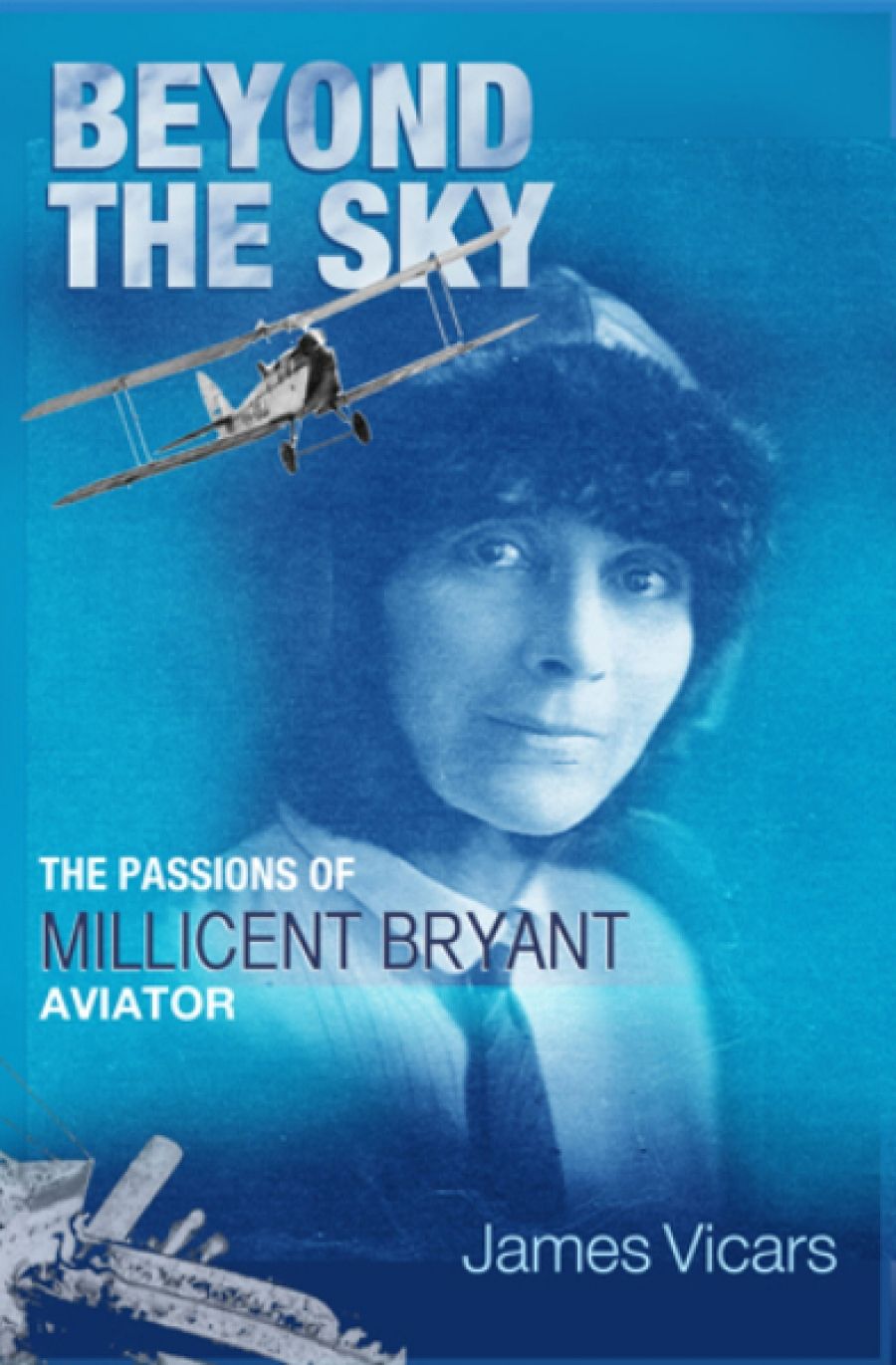

Members of the general public are likely to recognise the names of some of the pioneering female aviators. There is of course Amelia Earhart, the American who became the first female aviator to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. Here in Australia, many would recognise the name Nancy Bird Walton, who is known for gaining her pilot’s licence at the age of nineteen, as well as for helping to establish a flying medical service in regional New South Wales. But what of the Australian female aviator who is the subject of James Vicars’s début, Beyond the Sky: The passions of Millicent Bryant, aviator? Millicent Bryant (1878–1927) has largely passed into obscurity, but in her day she was a sensation. Vicars would like his great-grandmother to become once again a household name, celebrated for her achievement as the first woman in Australia – indeed, the first in the Commonwealth outside Britain – to gain a pilot’s licence.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Beyond the Sky

- Book 1 Title: Beyond the Sky

- Book 1 Subtitle: The passions of Millicent Bryant, aviator

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne Books, $34.95 pb, 360 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/4eP66o

Introducing Beyond the Sky in this manner makes it sound like a book likely to interest only plane spotters and other aerophiles. It also makes it sound like a traditional work of biography. Perhaps the book’s greatest accomplishment is that it is neither of these things.

The opening chapter of Beyond the Sky serves to alert readers to the book’s unexpected qualities. Vicars describes Bryant’s youngest son:

Inside his jacket a chill was spreading, rising like a subterranean river from the pit of his stomach up into his chest. As he turned into George Street from Circular Quay, the deepening shadows of the buildings seemed to touch him with the same icy foreboding that was threatening to engulf him from the inside.

Readers immediately learn from this description that Beyond the Sky is not a dry recitation of aeronautical achievements. Instead, it is filled with drama, suspense, and, perhaps most importantly, story. Readers also learn that Vicars takes the unconventional approach of inviting readers inside the hearts and minds of his historical characters. He does not shy away from speculation, nor is he reluctant to create dialogue where he could not possibly know what was said. The result is a much livelier – if slightly less accurate – reading experience. Indeed, Vicars has elsewhere written academic scholarship on the subject of ‘biofiction’ or the ‘biographical novel’, the practice of using fictional techniques to tell the story of a real person from history, and its potential for a deeper and richer form of truth-telling. But there is nothing about Beyond the Sky that feels the least bit academic; it is full of pathos, with the logos confined to source notes at the end.

Another thing the book accomplishes is answering the mystery of why Bryant has been mostly forgotten. Vicars begins with the collision of two boats in 1927 that resulted in the sinking of a Sydney ferry and the deaths of forty passengers, among them the forty-nine-year-old Bryant. She had gained her pilot’s licence seven months earlier. The competition between Bryant and two other women to become Australia’s first female aviator had been widely reported in the Australian media, and Bryant’s eventual victory meant, as Vicars writes, that she now ‘belonged less exclusively to her family and more, in some momentary way, to a mass of people she didn’t know’. However, Bryant never had the opportunity to build on this achievement and carve out a legacy for herself. Not long after her tragic death, she receded from the public consciousness.

Beginning Beyond the Sky with the death of its protagonist isn’t Vicars’s only bold structural choice. The next chapter sends readers two years back in time to Bryant’s first flight as a passenger in an aircraft piloted by a friend of her two eldest sons. From there, the book continues chronologically, following Bryant’s evolving association with the Australian Aero Club at Mascot in Sydney (site of the current international airport). By the time readers arrive back at Bryant’s fateful ferry ride, only half of the book has elapsed. For the second half, Vicars begins with Bryant’s birth in 1878 in north-western New South Wales. Once again, the narrative continues chronologically until, at the book’s conclusion, it reverts to Bryant’s first passenger flight. Though an unusual structure, it certainly works to build readers’ interest in this gutsy woman who decided to take up such a risky leisure activity. Why did she do it? What made her think it was possible, or even desirable? These are the sorts of questions that will persuade readers to follow Vicars even deeper into Bryant’s backstory in the second half of the book.

This structure does not, however, render all elements of Bryant’s life equally interesting. Her exploits as an early motorist who learned to repair her own vehicle are fascinating, less so her exploits as a businesswoman and small-scale property developer. These things help create the texture of life for a woman in Sydney and regional New South Wales in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but some of the details will interest only the historian, not the general reader.

One feature of the book that is thankfully never spared is the voice of its protagonist. Vicars undoubtedly laboured to capture this voice – drawing inspiration from a rediscovered collection of Bryant’s letters and other writings – but his rendering of it appears effortless. The strength of this narrative voice provides the solid foundation for Vicars’s exciting innovations with the biography genre. The result is a delicate but ultimately successful balancing act, much like that required of aviation’s pioneers.

Comments powered by CComment