- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Personally inflected

- Article Subtitle: A flawed look at autotheory

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The term ‘autotheory’, despite having been around since the 1990s, gained prominence after the release of Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts in 2015. Predictably, the emergent term elicited a flurry of academic interest, amid which Lauren Fournier – curator, video artist, filmmaker, and academic – established herself as a leading voice. Autotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing, and Criticism, Fournier’s first monograph, builds on her previous work, offering a condensed history of the genre and a number of case studies drawn from literature and the arts.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

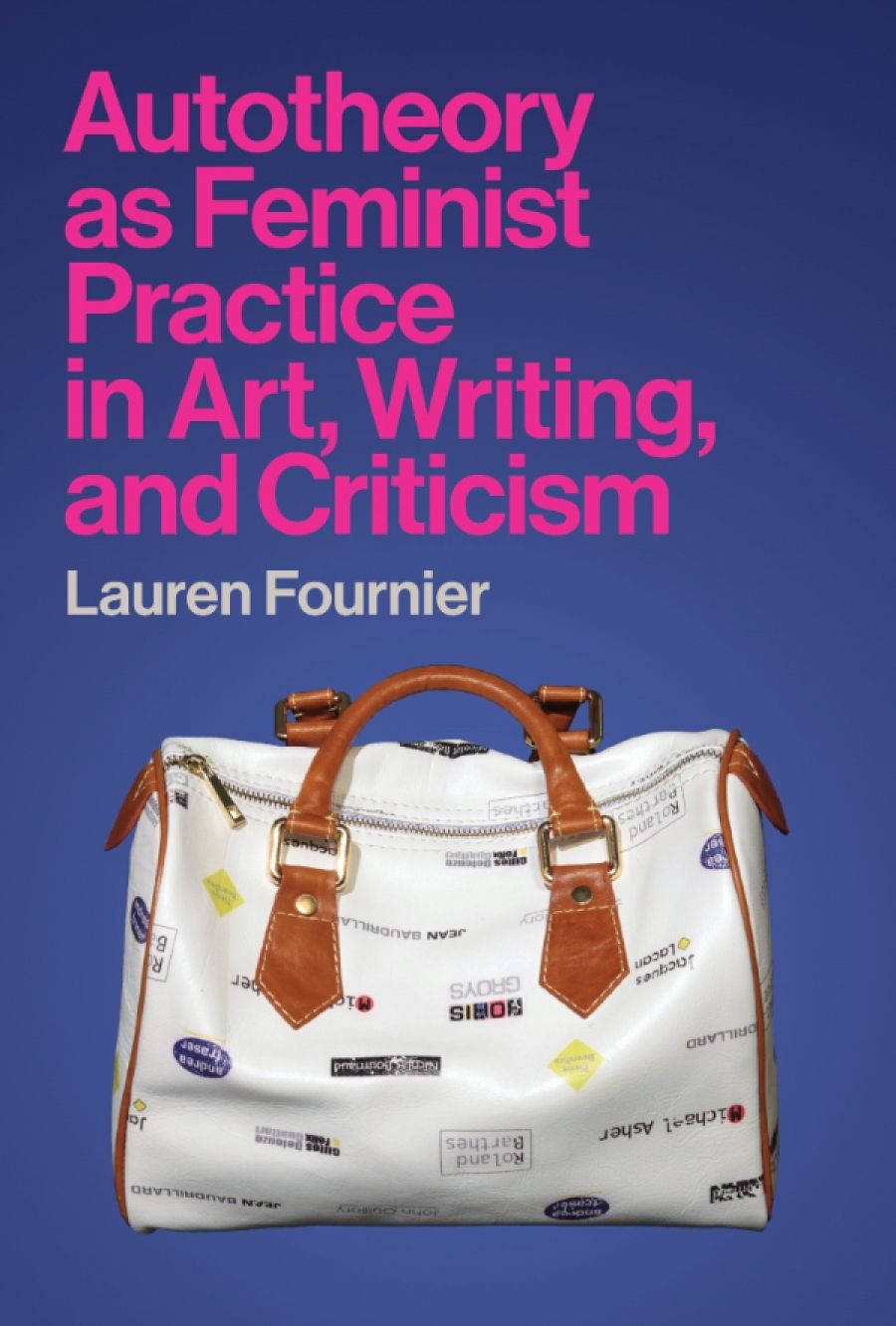

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Autotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing, and Criticism

- Book 1 Title: Autotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing, and Criticism

- Book 1 Biblio: MIT Press, $57.99 hb, 456 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/qn4r5L

The earliest autotheoretical book she considers is Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick (1997). She does not analyse the work of writers such as Gloria Anzaldúa, bell hooks, Audre Lorde, or Cherríe Moraga. What is frustrating about this is that Moraga’s Loving in the War Years (1983) was a case study through which Young articulated her understanding of the emergent genre and Anzaldúa spent years theorising and practising autotheory (though she didn’t call it that). Fournier offers her own broad definition of ‘autotheory’, describing it as

the integration of theory and philosophy with autobiography, the body, and other so-called personal and explicitly subjective modes … a self-conscious way of engaging with theory – as discourse, frame, or mode of thinking and practice – alongside lived experience and subjective embodiment, something very much in the Zeitgeist of cultural production today – especially in feminist, queer, and BIPOC … spaces that live on the edges of art and academia.

Lauren Fournier (photograph by Lee Henderson)

Lauren Fournier (photograph by Lee Henderson)

While Fournier recognises that some consider Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera (1987) to be an unacknowledged antecedent to The Argonauts, she does not give an account of the book itself. Nor does she mention autohistoria, a term that Anzaldúa coined in 1993 to describe art that ‘goes beyond the traditional self-portrait or autobiography, in telling the writer/artist’s personal story, it also includes the artist’s cultural history’, or autohistoria-teoría, which Anzaldúa arrived at in 2000 after working in this mode all of her professional life. In an interview with AnaLouise Keating, Anzaldúa described autohistoria-teoría as the blend of ‘cultural and personal biographies with memoir, history, storytelling, myth and other forms of theorizing paired with lived experiences’.

In Autotheory as Feminist Practice, autotheory is hard to distinguish from the personally inflected writing of thinkers such as Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, and Barthes. Further, it becomes decoupled from ‘theorising’ and instead functions through ‘engagement’, a term that can encompass simple citation as well as more radical auto-experimentation. Whereas Anzaldúa was interested in producing theory from a multiply inflected subject position and from working through autohistoria-teoría as a mode of radical philosophical praxis, Fournier’s understanding of the genre seems to require both less embodied experience and less theory, and is, as a result, less radical.

Fournier gives close chapter-length readings of Adrian Piper’s performance piece Food for the Spirit (1971), which Fournier reads as ‘conceptually metabolizing’ Kant and inscribing Piper’s self within a system that has otherwise excluded her; Nelson’s The Argonauts, which she turns to in exploring citational practices in written autotheory; and finally, Kraus’s I Love Dick, through which Fournier considers the ethics of exposure (and makes a ‘disclosure’ of her own regarding scandals that her potential and eventual external examiners were involved in).

In between, Fournier explores the cultural capital that theory carries in visual/performing art and considers citational practices in non-literary forms. In doing so, she curates and analyses a series of pieces – including from social media – that many readers would be unfamiliar with, offering lively and adroit (albeit often rather brief) discussions of each work. She includes works by women of colour, but only ones that engage with the Western tradition. Further, although decolonial practices have shaped autotheory since its earliest iterations, Fournier does not examine the genre’s decolonising potential until the conclusion.

Rather than explore early autotheoretical works that engaged with colonialism, or provide an extensive analysis of contemporary works that do the same, Fournier spends most of the chapter describing a David Chariandy reading and her personal response to it, including her irritation with other white audience members (‘I wanted to stand up and say, “Weren’t any of you listening to what David just shared with us?” Instead, I sat down and closed my eyes, cringing a bit’). That the centrality of decolonial practices to autotheory is not given space except in the conclusion is bad enough, but that Fournier focuses so much on her own experience in a section on autotheory’s decolonial potential adds insult to injury. Chariandy is the only thinker she writes on in this section.

Autotheory as Feminist Practice is an important contribution to an emerging field of study, particularly in its analysis of visual and performing art. Fournier makes clear the role women of colour have played and continue to play in autotheory’s development, but her failure to deeply consider autotheory’s rootedness in their embodied, embedded theorising casts it as nearly indistinguishable from the Western philosophy that preceded it and undermines its potential to disrupt the white, hetero, cis, male, and wealthy academy.

Comments powered by CComment