- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Mano a mano

- Article Subtitle: Napoleon and the papacy

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

To kidnap one pope might be regarded as unfortunate; to kidnap two looks like a pattern of abusive behaviour. Ambrogio A. Caiani tells the story of Napoleon’s second papal hostage-taking: an audacious 1809 plot to whisk Pius VII (1742–1823) from Rome in the dead of night and to break his stubborn resolve through physical isolation and intrusive surveillance.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): To Kidnap a Pope

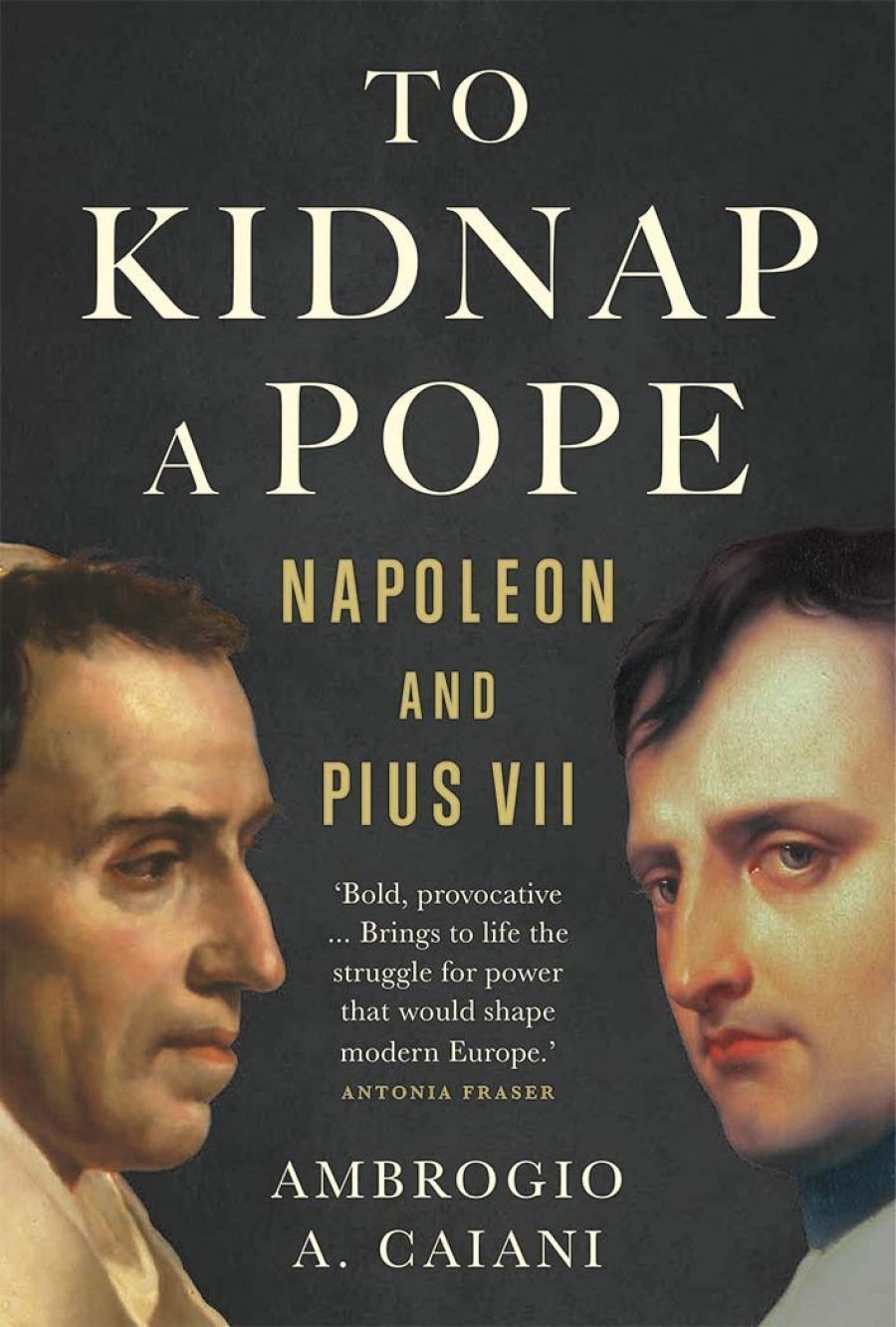

- Book 1 Title: To Kidnap a Pope

- Book 1 Subtitle: Napoleon and Pius VII

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press, US$32.50 hb, 369 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/7m53Ry

The victor of Austerlitz, Master of Europe, Emperor of the French, pitted himself against a quiet, unassuming former monk, but this time his legendary force of will was found wanting. Napoleon’s failure to make Pius submit was arguably his greatest setback until the retreat from Russia in 1812. It was certainly no less momentous, for the pope’s ill treatment shocked pious Europe: could it be right to disrespect the Holy Father in this way? Even non-Catholic powers, to whom the papacy seemed a quaint anachronism at best, looked on queasily at the precedent. The emperor’s own officers fretted over repercussions if Pius should die in custody, as his predecessor, Pius VI (1775–99), had done. Conservative opinion, a key part of Napoleon’s coalition, would hardly tolerate a regime that saw popes as quite so disposable.

Napoleon’s reputation never truly recovered from the disquiet he generated by how he treated his clerical foe. For some, the humiliations later inflicted on him were, in part, justified by the vindictive approach he himself had adopted. For Caiani, Napoleon’s treatment of Pius gives us the measure of the man. However, it also revealed an important fault line within the French imperial project itself.

It should not have been this way. That much Caiani makes clear. When Napoleon seized power on 18 Brumaire, it was as part of a counter-revolution against the threat of yet more Jacobinism. The then consul, later emperor, made a signature strategy of uniting moderate elements from among the Revolution’s winners and losers. That way they might together keep out the extremes. The Catholic Church was central to this approach, for her ancient institutions had suffered much from the viciously anti-clerical Revolution of 1789. Napoleon wanted his rule to be different: to recognise the value of religion and the place of the Church in the construction of civil society. True, he had come into conflict with Pius VI, but that conflict could be explained away as essentially political: a campaign to make the Papal States acknowledge French supremacy. And Napoleon was willing to negotiate with Pius VII after the Conclave of Venice elected the latter in 1800. Perhaps some compromise in which the pope retained his rights in Rome could be reached after all – at least if he was also willing to legitimise Napoleon’s designs for a refashioned French Church?

Caiani’s narrative has Pius and Napoleon dancing around each other throughout the early 1800s like two scorpions. An initial accord, the Concordat of 1801, did not last. Both sides applied pressure continuously. Was it Pius who crossed the Rubicon when he excommunicated the emperor after French troops replaced the papal standard with the tricolour throughout Rome on 10 June 1809? Or was it Napoleon who made the fateful move when his dominance after Austerlitz led him hubristically to ride roughshod over previous agreements or understandings?

Either way, lack of trust on both sides sealed their collective fate. Eventually, the French brigadier general Étienne Radet knocked on the door of the pope’s private apartments in the Quirinal Palace: his troop of more than 700 men had brought the Swiss Guard to surrender and now he had come to arrest the pontiff. Five years would pass until Pius saw Rome again. He would be a very different man when he returned: older, more fragile, and extremely bitter. This did not bode well for the future of the Papal States, but it was the price of his resistance. Except for a brief moment of weakness in 1812, when a draft Concordat of Fontainebleau had been prepared, Pius had indeed held firm. Romans welcomed him as a triumphant hero–liberator, although his only gesture of gratitude was to restore one of Europe’s most repressive regimes.

Caiani’s unique contribution in this work is to have set aside traditional, partisan tellings of this tale as good versus evil, secular versus religious, or state versus church. Instead, this version, even-handed and detailed in its contextualisation, is about two charismatic leaders going mano a mano. But what is lost and gained by understanding events primarily through its two protagonists’ personal struggle? Caiani is strangely reluctant to pontificate on how exactly a clash might have been avoided. Napoleon certainly fits into a long line of political leaders who underestimated religious leadership’s moral authority and cultural sway. But his plans for reforming the Church may well have been sound, and intransigence towards them self-serving. Napoleon, unlike the Jacobins, wanted to save clerics from themselves, not destroy them. Was it not Pius, then, whose leadership failed in not recognising this? Pius’s own tragedy was different: he felt he had to protect the rights of the Holy See, whatever the personal cost. And the Pius who persecuted Jews and Freemasons after 1814 seems a very different man from the one who preached on Christmas Day, 1797, that democracy and liberty were entirely compatible with sacred scripture, a change that highlights how high that cost was. Yet it is not clear that Pius’s approach was the wrong one for the Church, which is still here, or for the papacy, which saw its standing in and authority over the Church enhanced. A ‘conservative’ like Napoleon surely ought to have better grasped the significance of Pius’s dilemma? In the end, both priests and Frenchmen paid a high price before their leaders had done. Pius, ever the martyr, pleaded clemency for Napoleon to the last.

Comments powered by CComment