- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Fertile ground

- Article Subtitle: A collection of writings on writing

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘When I first began reading Nam Le’s Love and honour and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice, I was sceptical: a story about a writer writing a story? A writer at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, no less? Isn’t this a little self-indulgent? Hasn’t this been done before?’

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

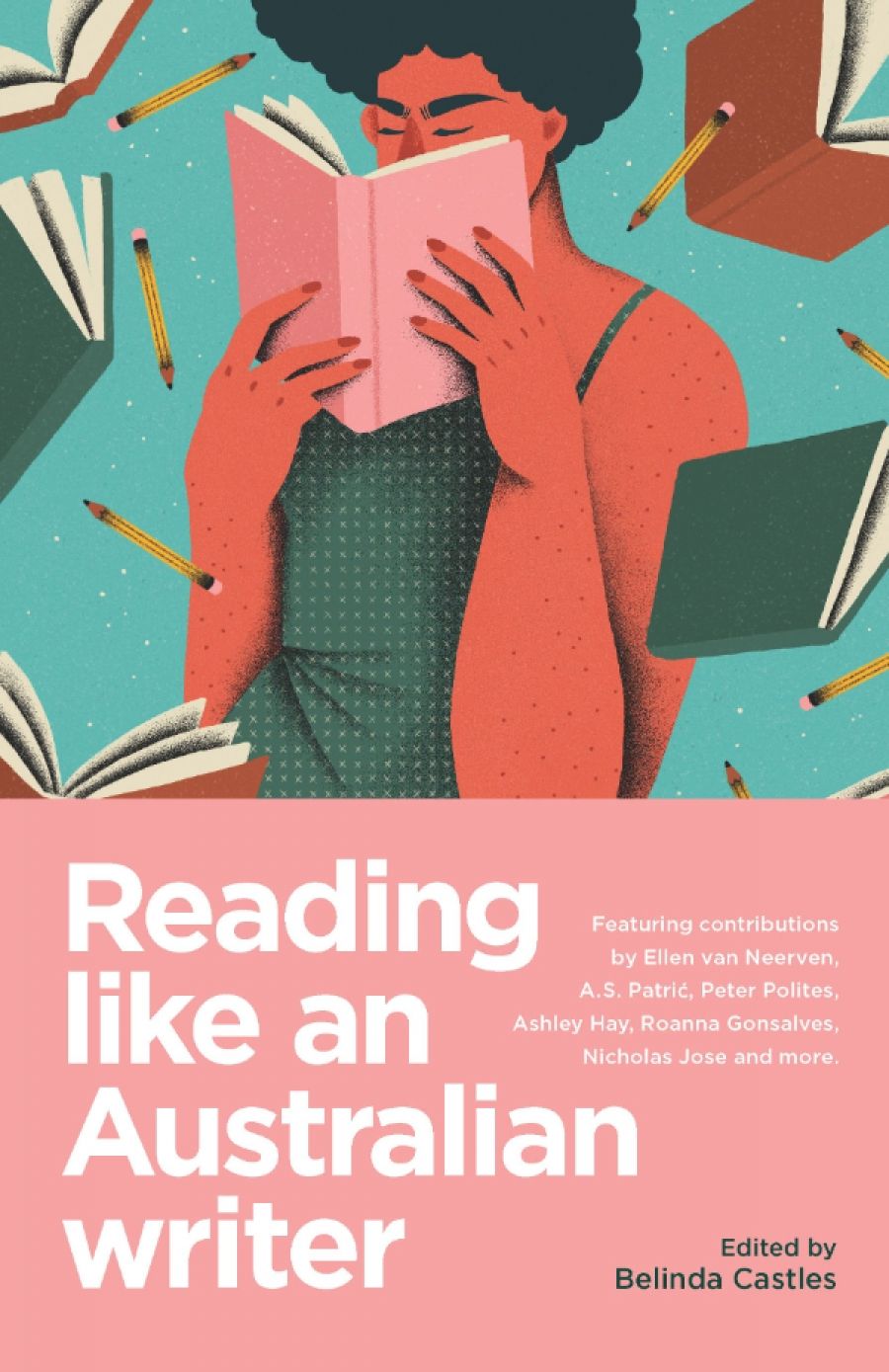

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Reading like an Australian Writer

- Book 1 Title: Reading Like an Australian Writer

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $34.99 pb, 368 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/6be20r

Of course, readers like nothing more than learning about artists, whether painters or writers or musicians. There is an enduring fascination with creativity: what it is, where it comes from, what it feels like. Equally, you only have to look at the proliferation of podcasts and books on writing to realise that writers also want to read about other writers, for similar reasons. How did they get there? How do they do it? Writing about writers, whether novels or non-fiction, is fertile ground.

Reading Like an Australian Writer is described as ‘a love letter to the magic of reading. To the spark that’s set off when the reader thinks … I can do this too.’ Some of Australia’s best writers reveal their ‘moments of revelation’ in their favourite Australian books. But that’s not quite how it pans out. The collection, which includes twenty-six writers from the established to the emerging, varies wildly in approach and tone. Some essays are very academic, others more personal. Some deal with close-up matters of craft, others with broader conversations happening in Australian literature (as an indication of just how of-the-moment the collection is, at least two examine Laura Jean McKay’s novel The Animals in That Country, which won the 2021 Victorian Prize for Literature). Beyond the fact that both the subject and the writer of each essay are Australian, there seems to be no particular thread uniting the essays.

Interestingly, the concept of ‘Australian-ness’ is barely touched upon. Rather than using the collection as an opportunity to examine what the selected books might say about the state of Australian writing, the writers mostly talk as they might about any book they love. On one hand, this is refreshing (in his essay on David Malouf’s Ransom [2009], A.S. Patrić describes Australian writing as ‘often self-referential to the point of being hermetically sealed’), but it feels like a missed opportunity. If the Australian-ness of both writers and writing is not the point, then what is? Why this collection at this particular time?

To her credit, Castles acknowledges this vagueness from the outset. ‘As a picture of Australian fiction, it is energetically incomplete, part of a conversation that is always moving forwards,’ she writes. But with no obvious thread connecting the essays, and a lack of broader critical engagement, the collection can’t help but feel incohesive.

Nonetheless, it’s hard to fault the calibre of most of the essays, or the range of backgrounds and perspectives the writers represent. In the first essay of the collection, Ellen van Neerven writes movingly about the joy of finally seeing a young mixed-race Aboriginal woman represented in the pages of Tara June Winch’s Swallow the Air (2006).

Later, Tweed Goori woman Mykaela Saunders (winner of the 2020 Jolley Prize) examines the idea of ‘everywhen’ or ‘all times’ as a way of understanding the structure of Alexis Wright’s masterpiece, Carpentaria (2006). Asian-Australian perspectives are brought to our attention, both in Hoa Pham’s analysis of the Buddhist concept of ‘interbeing’ in Chi Vu’s novel Anguli Ma: A gothic tale (2010), and in Fiona McFarlane’s dissection of Nam Le’s short story ‘Love and Honour and Pity and Pride and Compassion and Sacrifice’ (2009) to discover how it deals with issues of generational trauma and inheritance. In ‘Read to Find Yourself’, Peter Polites reflects upon the books that influenced him as a gay Greek-Australian writer.

Not surprisingly, several essays concern what feels like the increasingly small gap between real life and the popular tropes of science fiction novels. ‘How might we imagine dystopias differently if we accept we are living in one now?’ ask Rose Michael and Jane Rawson in their essay ‘Reading Crises, Writing Crisis’, which interrogates what dystopian fiction can teach us about living and writing in an almost apocalyptic world. In ‘Ten Thoughts on Fiction That Slays’, Beth Yahp uses Julie Koh’s short story collection Portable Curiosities (2016) to examine the role satire plays in a world that already seems ridiculous. And in ‘An Obsidian Mirror’, Patrić uses David Malouf’s novel Ransom to reflect our own times back at us through the lens of the myths of Ancient Greece.

Given the necessity of most writers to teach to make ends meet, there is a strong element of craft running through the collection. ‘A story is like close-up magic, and even if you try to practise magic yourself, it doesn’t ruin the thrill of it for you when you sit in the audience and admire somebody else doing it with passion, skill and bravado,’ says Cate Kennedy in the introduction to her almost line-by-line analysis of how Tim Winton builds tension in the first seven pages of his novel Breath (2008). An equal act of ‘close-up magic’ comes in Emily Maguire’s insightful analysis of how Elizabeth Harrower uses language to create the moment of epiphany in her short story ‘The Fun of the Fair’ (2015). Language also features strongly in Castles’ own contribution to the collection, an examination of her affection for Peter Carey’s Oscar and Lucinda (1988).

There’s much to like about Reading Like an Australian Writer. It has a wealth of information about the process by which good writing is made, and about analysing old stories with new perspectives. The anthology would have benefited from a sharper focus and a better attempt to integrate the collection within a wider critical context. Writers might enjoy reading about other writers, but only if there’s something to learn. Reading Like an Australian Writer has that in spades.

Comments powered by CComment