- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: LOL!

- Article Subtitle: A novel of revenge

- Online Only: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

S.L. Lim’s second novel, Revenge, begins with an ‘all persons fictitious’ disclaimer. The paragraph concludes: ‘Any resemblance to actual events, locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental. LOL!’

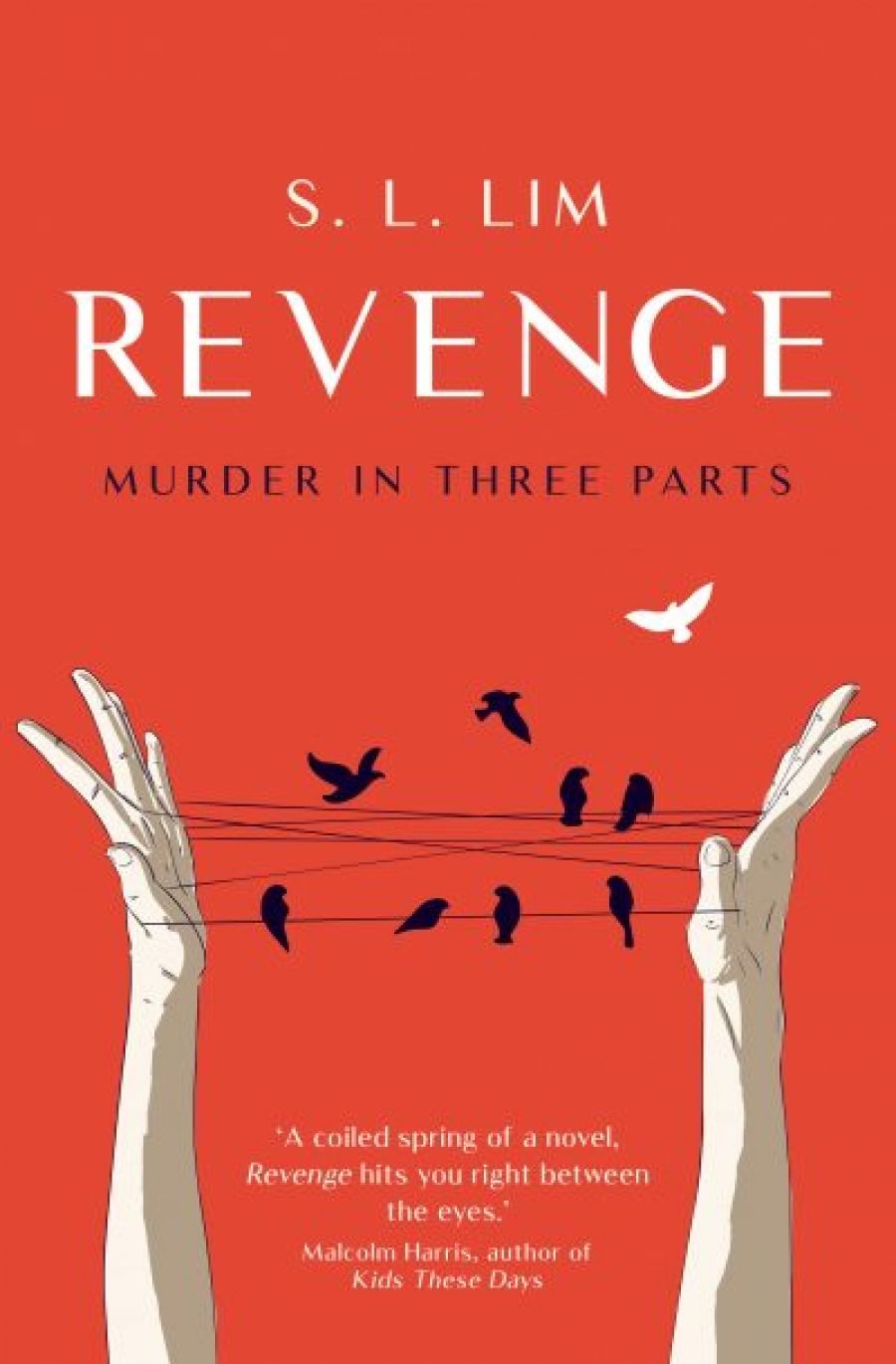

- Book 1 Title: Revenge

- Book 1 Subtitle: Murder in three parts

- Book 1 Biblio: Transit Lounge, $29.99 pb, 240 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://booktopia.kh4ffx.net/mgg9xe

Eleven-year-old Yannie is tormented by her older brother, Shan. By the first of the prologue’s seventy-five pages (titled ‘The Demon Brother’, it reads more like the novel’s first section), he has already thrown her halfway across the room. Yannie, because she is precocious, is treated with contempt by her patriarchal household. ‘Girls are too hard,’ her mother intones. But it is not until Yannie learns she must forfeit an offer from Malaysia’s top university – allowing Shan to further his studies overseas – that she fully grasps the corollary of being female in her traditional, working-class milieu.

Later, in middle age, Yannie visits Shan’s upper-middle-class family in Sydney, where she finds herself entangled in an eerily familiar dynamic. Yannie is both drawn to and resentful of her niece, Kat, in whom she sees her own atrophied potential being nurtured and encouraged. Her murderous intent towards Shan, which leaned towards hyperbole in her adolescence, has mellowed to a detached, yet sinister, fascination with his lifestyle. Although elements of the plot feel dictated by Lim’s sustained critique of class and capitalism, it is Yannie’s cognitive dissonance when it comes to Shan’s family and their wealth that forms the strongest points of this book.

From her writerly ambitions, to her longing for her friend, Shuying, Yannie’s inner life is assuredly wrought. However, when other characters appear – particularly Yannie’s family members – the veneer of fiction seems to splinter. The author’s apparent desire for fictional catharsis eclipses the narrative, stilting the dialogue. This is most noticeable when Yannie’s mother speaks; in one scene she berates Yannie for refusing to wear a dress: ‘Oh, you think you are so clever. Bloody shit, what is wrong with you, Yannie?’ In a later scene, when Kat insists on studying fine art, her mother, Evelyn says, ‘You bitch. You bloody, bloody bitch.’

Given the score-settling aspect of the novel’s second act, and taking into account its tongue-in-cheek disclaimer, it appears the author’s score-settling extends beyond the realm of the novel, often at the expense of its success.

Comments powered by CComment