- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘They love you still’

- Article Subtitle: Cy Twombly and the spectre of antiquity

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

If you were fortunate enough to take Franz Philipp’s course in Medieval and Renaissance Art at the University of Melbourne in the 1960s – the old Fine Arts B – you would have quickly encountered Erwin Panofsky’s masterpiece, Renaissance and Renascences in Western Art (1960). It set forth authoritatively the argument that from the Carolingian revival in the eighth century through the Ottonian and Romanesque survivals, culminating in the Italian Renaissance of the quattrocento and cinquecento, Western art was haunted by the spectre of antiquity. Admiration for its mighty surviving works throughout western Europe turned steadily towards emulating them.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

.jpg)

- Article Hero Image Caption: <em>Empire of Flora</em>, Cy Twombly, Hamburger Bahnhof Museum, Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin, Germany (agefotostock/Alamy)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Empire of Flora, Cy Twombly, Hamburger Bahnhof Museum, Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin, Germany (agefotostock/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Cy Twombly

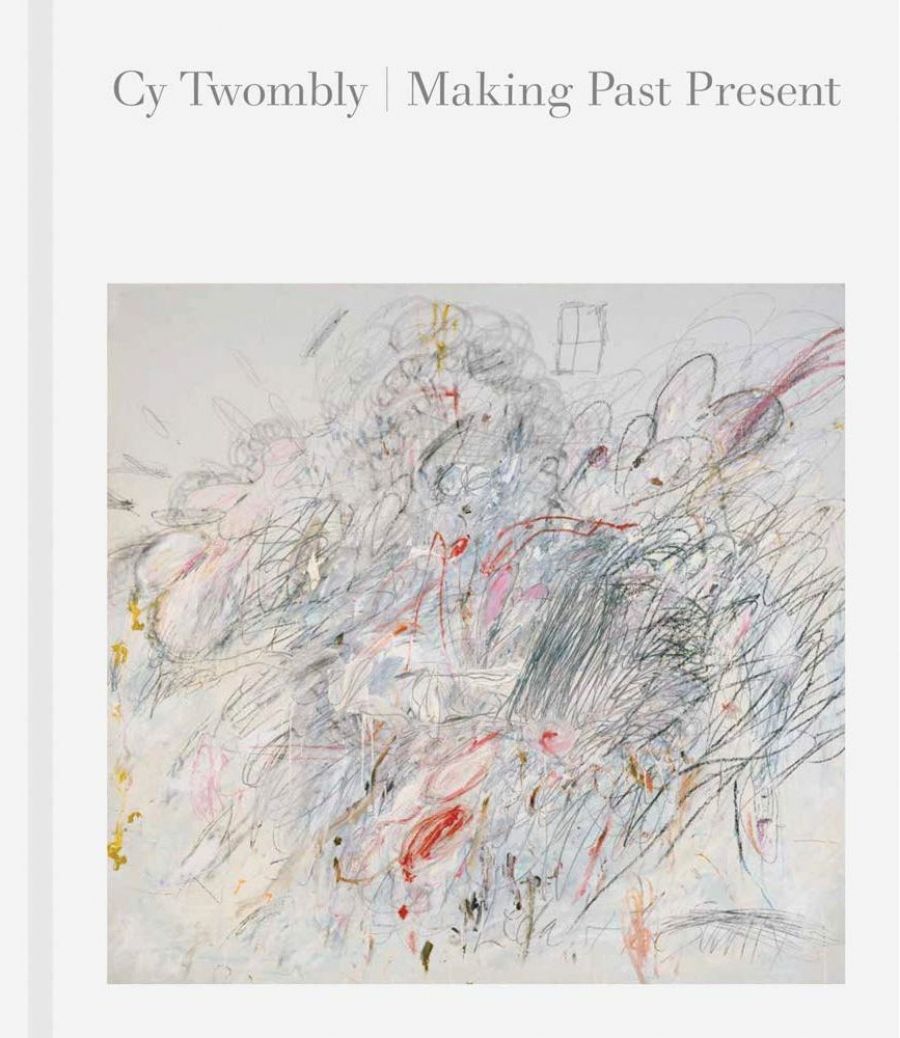

- Book 1 Title: Cy Twombly

- Book 1 Subtitle: Making past present

- Book 1 Biblio: MFA Publications, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, US$65 hb, 264 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/4eekJn

To a callow youth, this argument presented a commanding view of the Western imagination. It was a ‘deep state’ theory of the sprawling mass of Western art. It was easy to see it working its way through the seventeenth century – all those vigorous reworkings of the Belvedere Torso by Rubens, to say nothing of Poussin and Claude. To be sure, it gradually became codified in the schools and academies of the eighteenth century. It had its moments of absurdity, such as Goethe tearing through Assisi intent on seeing the Roman Temple of Minerva and skipping the early Giotto cycle of the life of St Francis in the Upper Church of San Francesco. Eventually, the impulse of the antique calcified in the Salons of Paris. The triumph of modern art compelled antiquity to relinquish its grip over the Western imagination.

But that makes one feel queasy. The guiding inspiration of Western art for two thousand years dismissed at the shake of a brush? A moment’s reflection and you will bring to mind James Joyce’s Ulysses, whose frame is provided by Homer’s Odyssey. Keep musing and you will recall Picasso’s Vollard Suite, with its artists and models in continuous dialogue with classical gods and goddesses. The post-and-beam architecture of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe owes its poetry to the proportion and measure of classical architecture.

Now in our lifetime we have Cy Twombly’s sustained enquiry into, argument with, and homage to antiquity: its gods and heroes, its myths and history. Nobody could doubt Twombly’s avant-garde credentials. Indeed, his scratchy, improvisatory method of working, his cryptic allusions to persons, events, and poetry, have from time to time challenged taste. And not just that of the Eltham Daubers but the likes of Donald Judd who, in 1963, said of Twombly’s Nine Discourses on Commodus: ‘There isn’t anything to these paintings.’ The present catalogue, invaluably, provides the fullest account of Twombly’s classical impulses.

No major American painter since the nineteenth century has immersed themselves so fully in the environment and mores of the classical past. In 1957, he left America for Rome, which remained his base until his death in 2011. He lived for a period in Gaeta in southern Italy and spent most of his summers in a palatial villa in Bassano in Teverina, an hour’s drive north of Rome, buried in the lushness of Lazio green. He collected antiquities, some notable Etruscan works as well as Roman statuary and portraits, and placed them prominently in his Rome house and at the villa. They were his household gods.

The fragmentary nature of so much classical art and the fragmentary quality of Twombly’s paintings and sculpture form an intense connection. An explosion of paint can break into fragments that scatter across the canvas like a meteor shower. Inscriptions, often hard to read, elusive rather than illuminating, can break off or be erased by Twombly. They retain what Roland Barthes, a shrewd observer of Twombly, called ‘the bait of meaning’. We are led into this world, made cohesive by the sheer energy of Twombly’s markings, be they brush marks, scribbled writings, collaged elements, random splashes of paint. We never doubt his intensity of feeling.

Twombly once observed that ‘to paint involves a certain crisis – a crucial moment’. There is always in his facture a sense of the pent-up being released. Professor Mary Jacobus of Cambridge and Cornell quotes Theodor Adorno to good effect: ‘the fragment is a philosophical form which, precisely by being fragmented and incomplete, retains something of the force of the universal.’ She rightly says that Adorno could be paraphrasing Rilke’s marvellous ‘Archaic Torso of Apollo’. Although headless ‘his torso / is still suffused with a brilliance from inside / like a lamp … otherwise / the curved breast could not dazzle you so, nor could / a smile run through the placid hips and thighs / to that dark center where procreation flared’. The poem gathers to its triumphal conclusion ‘… for here there is no place / which does not see you. You must change your life.’

Twombly, an avowed admirer of Rilke’s, seeks that intensity of engagement, particularly when approaching the divinities. The names of gods and goddesses are painted assertively across the surface or scrawled in graphite. A whole painting comprises Aphrodite in rubbed orange paint above her origins, Anadyomene, the one who rises fully human from the sea. The painting is like a weathered epitaph. It is we the beholder who speak the god’s name, involuntarily, evoking him or her, making them present. The catalogue takes its epigraph from C.P. Cavafy: ‘Because we smashed their statues all to pieces, / because we chased them from their temples / this hardly means the gods have died / O land of Ionia they love you still …’ Twombly’s written deities keep them alive in the mind of the viewer.

There are mythologies like MoMA’s convulsive Leda and the Swan, a seething mass of force and resistance, of revelation and erasure. Did Rilke’s Leda play a part in Twombly’s creation of this coupling of god and girl:

And she, all openness, already guessed

Who it was coming in the swan knew that

The thing he asked of her dazed resistance

Could no longer hide from him. A swoop,

And his neck butting through her hands’ weak hindrance …

The most powerful of Twombly’s encounters with the antique is unquestionably the ten-painting sequence, Fifty Days at Iliam, purchased by the Philadelphia Museum of Art for $2 million in 1989 and permanently on display in a room that the artist partially designed. ‘Iliam’ is Twombly’s idiosyncratic way of spelling Ilium (Troy). The ‘a’ is meant to recall Achilles to the mind of the viewer. The subject of the series is the conclusion of the decade-long Trojan War, a foundational event in Western consciousness. The room has only one entrance/exit, no windows – the effect is tomb-like.

The series parallels the antagonists. The Heroes of the Ilians balances a complementary Heroes of the Achaeans. There are large, savagely drawn and painted battle scenes for each army. The end of all this is the huge (490 centimetres long) summoning of heroes: Achilles, Patroclus, and Hector. They are represented by swirls of paint. Hector is commemorated in neutral tones; Patroclus by gray-black pigment shot with traces of red crayon; Achilles, heart-shaped in red pigment, reads like a pool of blood. One shudders involuntarily before it.

When the series was first purchased with all the accompanying news about how it would have a dedicated space within the museum, there was much uncertainty about the wisdom of the acquisition. So much money on one living artist, given such unprecedented attention within the museum. Naturally, that all died down a long time ago. The Twombly room reads like a memorial for the dead in all wars.

Comments powered by CComment