- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letter collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Free music

- Article Subtitle: A subtle volume with poignant depths

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Compiling a selection of letters for publication is a vexing task. Inclusions and exclusions tend to satisfy only the editors. Specialist readers will inevitably find their particular interests inadequately represented, while others will find material included to be offensive or inappropriate. The success of this volume has been secured partly because both editors have worked on books of Grainger letters before: Teresa Balough with Comrades in Art: The correspondence of Ronald Stevenson and Percy Grainger, 1957–61, and Kay Dreyfus with her ground-breaking volume The Farthest North of Humanness: Letters of Percy Grainger, 1901–1914. Also, only 181 letters between Cross and Percy and Ella Grainger were available, which minimised the scale of the cull. The editors chose to exclude seventy letters, the quotidian content of which immediately flagged their redundancy.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Distant Dreams

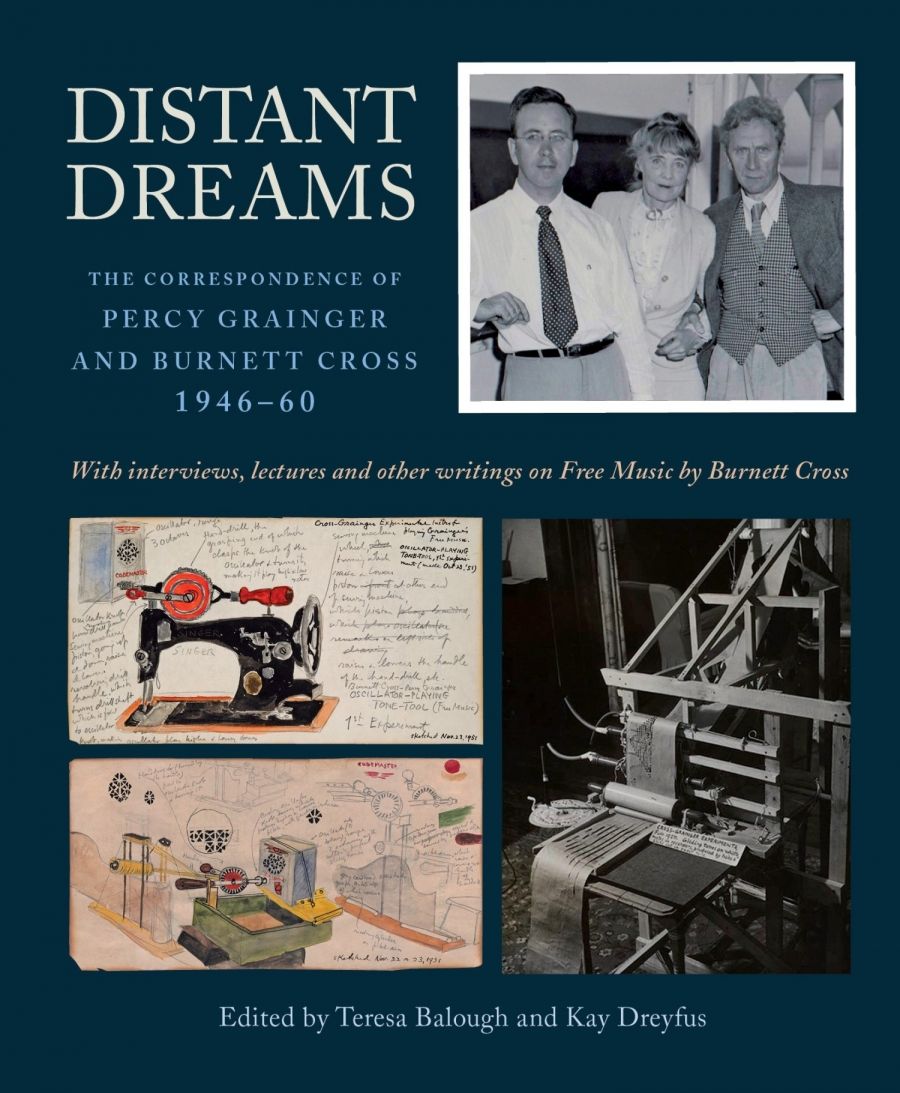

- Book 1 Title: Distant Dreams

- Book 1 Subtitle: The correspondence of Percy Grainger and Burnett Cross, 1946–60

- Book 1 Biblio: Lyrebird Press, $40 pb, 199 pp

Included in the volume are seventy-six letters from Percy Grainger to Burnett Cross, a musician, science teacher, editor, and writer who lived not far from Grainger’s White Plains home, in Hartsdale, New York State. Thirty-one letters from Cross to Percy were included, and four from Ella to Cross. These constitute Part 1 (‘A Very Happy Occupation’) of Distant Dreams. The second part (‘A Man of High Intelligence and Lively Imagination’) presents nine ‘interviews, lectures and other writings on Free Music’ by Cross alone. Together these writings bear witness to innovative – if at times rather Boy’s Own – musical adventures, as Cross and Percy attempt to fulfil the composer’s lifelong ‘distant dream’ of a truly ‘free’ musical form unrestricted by melodic, harmonic, temporal, or physical restraints. How they built the equipment to do this is ingenious, sometimes amusing, often confusing, but always impressive. A tip for the prospective reader: Cross’s 1978 document ‘Free Music’ and Warren Burt’s excellent foreword together serve as an outstanding ‘user manual’ for the letters and other articles, so read them first. The struggle that engulfed the Graingers and Cross – just how to construct mechanisms that would play such music – will make much more sense if you do. Immediately, Grainger’s colourfully named ‘Kangaroo-Pouch’, ‘Estey-Reed’, or ‘Electric-Eye’ ‘tone tools’ will become familiar devices you understand, not eccentric fantasies that are hard to appreciate.

Distant Dreams is more than a history of musical instrument building, however advanced such instruments might be. It is a subtle volume with poignant depths. The letters reflect the American world view of the 1950s, highlight the role of science in society and education, and attest to a relationship between the three correspondents of profound quality and stirring richness. We witness the reconciliation of Grainger’s mercurial enthusiasm and Cross’s flat-lined cautious, logical methodology. A fusion took place, in which two characters, two traditions, worked together, not simply side by side but as complements to one another, shoring up each other’s work and standing in when the other stumbled; or in Grainger’s case, could barely even stand. Cross, we read, was ‘motivated by a lively curiosity, and an absolute absence of fear of failure’. Cross wrote to Grainger on 8 June 1959, describing his latest reading, The Sleepwalkers by Arthur Koestler, which examined the work of Copernicus, Kepler, and Galileo, among others. Cross noted that they endured wrong turns and dead ends, but kept going because ‘the actual path of discovery ... is more like sleepwalking than a logical progression’. By contrast, Grainger, despite his musical fame, was wracked by fear – a fear of performing, of police scrutiny, of war, of disease, of burglars. Cross was deeply committed to the integrity of scientific method, and wrote about it for his teaching peers. Grainger knew nothing about science but placed his faith in art, music, and humanity itself as sources of universal good. Both were driven by evangelistic zeal.

The initial correspondence began in the months following the end of World War II. The tone is formal, mildly distant, and mutually respectful. Cautiously they got to know one another, until an affection and commitment to their shared aims was established. Often Percy complimented Cross effusively in their exchanges, while Cross regularly calmed Grainger, without indulging in his maudlin introspection. By the end of July 1950, Percy begins to sign his letters no longer with ‘Yours ever’, or just ‘Percy’, but with variations on ‘Love to all from Ella and Me’. On September 2 that year, Cross signed off with ‘My love to you both.’ Within the month, Elizabeth Burnett, Cross’s mother and music director of the First Baptist Church of White Plains, began organising a concert of Grainger’s music.

This friendship came at a crucial time. Over the next fifteen years, Grainger’s prostate cancer increasingly sapped his energy, his medication and pain challenged his concentration, and problems of continence demoralised him. The letters show how Cross stepped up, taking a lead and providing the support that enabled Free Music to become a reality.

The photographic records in the book are excellent, and add a crucial dimension to the work’s clarity (page 20, and pages 152–53 are good examples of this). Cross undertook a number of photographic assignments for Grainger, including those of various composers’ eyes, to support some of Grainger’s racial views concerning blue eyes, ‘Nordic’ origins, and genius (there is no evidence Cross shared such views). Grainger was not afraid to declare the importance of this work, writing in a letter to Cross dated 27 May 1953: ‘But the securing of the eye photos is so important that I greatly rejoiced when you declared yourself willing to do it & I don’t greatly care whom I incommode in the matter – including your dear self.’

The composers subjected to this (Walton, Vaughan Williams, and Bax, among others) were more amused than incommoded. When a composer did not seem to have the requisite blue eyes, Grainger blamed the light, or other elements. So when Vaughan Williams’s eyes betrayed some purple and hazel, Grainger declared to Cross (13 June 1953), ‘let us rescue as much Nordicness out of V. Williams’s eyes as we can, say I!’

From a structural viewpoint, Lyrebird Press has produced a stunningly elegant volume. Its robust dimensions help to do justice to the lush collection of illustrations. The print is easy on the eye, ensuring that editorial notes on the letters are provided at the corresponding side of the text to which they refer. This means the notes get read: unlike endnotes and footnotes, you actually want to read these side notes; they are not at all labour-intensive, although at times they are perhaps a little too discursive.

Despite Grainger’s many fears, he impressed Cross as a brave man in his commitment to the belief that Free Music was the way music must, in time, go. ‘When that time comes, I think Percy Grainger’s achievement as a pioneer will be fully recognised and saluted.’ Distant Dreams helps make that happen, and the distance a little less.

Comments powered by CComment