- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Laureate of polysituatedness

- Article Subtitle: Paul Muldoon’s liminal poetry

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Dislocations is a product of the Irish diaspora. Its editor is a Western Australian who claims his Irish heritage from Carlow and Wicklow; its subject was brought up on the border between counties Armagh and Tyrone in Northern Ireland, and emigrated to the United States in 1987. There is, then, a biographical precedent for John Kinsella’s sharp characterisation of Paul Muldoon’s work as ‘a liminal poetry that lives both sides of any given border … in an ongoing state of visitation with its roots in linguistic and cultural reassurance’.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

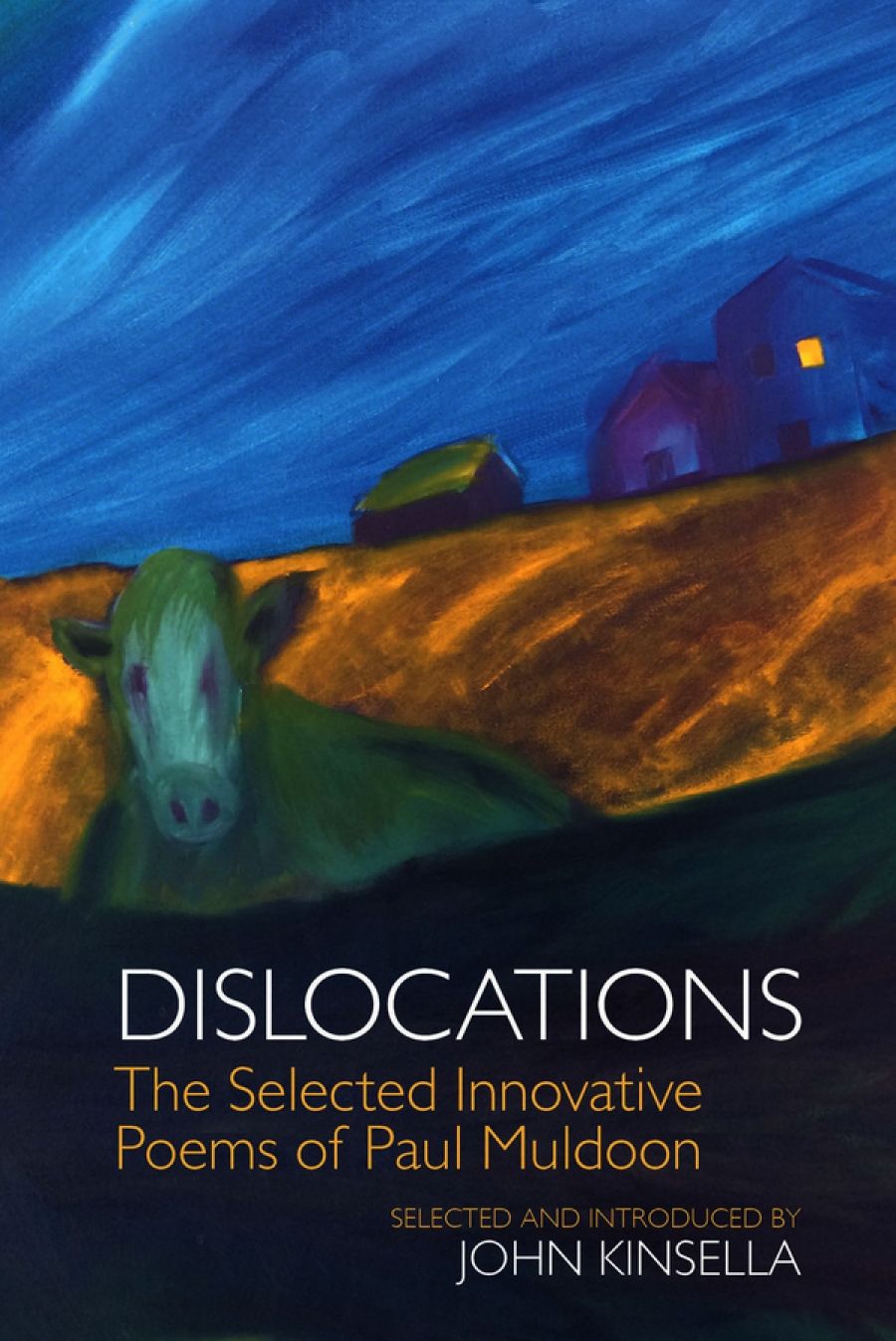

- Book 1 Title: Dislocations

- Book 1 Subtitle: The selected innovative poems of Paul Muldoon

- Book 1 Biblio: Liverpool University Press, £20 hb, 228 pp

‘Poly-’ is a prefix that often attaches to this polymathic and polymorphous poet. Kinsella writes of Muldoon’s search for forms capacious enough to ‘polysynthesize … his fragmented vision’. One of the best-known lines in ‘Incantata’, an elegy for the American-Irish printmaker Mary Farl Powers, has the poet recall Powers’ nickname for him, ‘“Polyester” or “Polyurethane”’, as a testament to his ‘tendency to put / on too much artificiality’. In ‘Capercaillies’ (Gaelic for ‘horse of the woods’ we are informed), a character asks macaronically, ‘Paul? Was it you put the pol in polygamy / or was it somebody else?’ Much of Muldoon’s virtuosity as a verbal technician is invested in this sort of philological banter as well as in his handling of intricate stanza forms (the rhyming sets structuring the octaves in ‘Incantata’ also determine the sestina variations in ‘Yarrow’). The extravagance of Muldoon’s designs – sometimes down to the letter in the case of ‘Capercaillies’, where the left-hand margin reads: ‘IS this a New yOrker Poem oR whaT’ – has sometimes exasperated critics. But one of the virtues of this volume is the manner in which it shows the continuities between such formal prodigies and Muldoon’s ‘milder inventions’.

At first glance, a poem such as ‘Promises, Promises’ seems a straightforward lyric about the pathos of displacement. The speaker is in North Carolina, ‘stretched out under the lean-to / Of an old tobacco-shed’ and nostalgic for ‘the low hills, the open-ended sky’ of his homeland. Yet the innocence of this alienated pose (‘What is passing is passing me by’) is compromised by the historical consciousness that creeps in with the second stanza: ‘I am with Raleigh, near the Atlantic, / Where we have built a stockade / Around our little colony.’ The speaker imagines himself participating in England’s first attempt to settle on American soil. The so-called ‘Lost Colony’ at Roanoke Island vanished almost entirely within three years of its establishment in 1587. In the poet’s reverie, the only traces that remain are a ‘glimpse … here and there’ of ‘one fair strand in her braid, / The blue in an Indian girl’s dead eye’. Muldoon specialises in such uncanny shock effects: of the familiar abruptly defamiliarised (as with the temporal shift between stanzas) or the unfamiliar suddenly rendered familiar (as with the recognition occasioned by the dead Indian girl’s colouring).

This sense of the uncanny also haunts Muldoon’s rhyme schemes, which deploy a whole range of effects from ‘full’ assonantal rhymes (‘quiet’/‘diet’) to subtler consonantal chimes (‘souls’/‘sails’). This fluid approach means that it is sometimes difficult to ascertain the limits of a rhyming set – are we meant to hear some residue of ‘Carolina’ in ‘colony’ or even ‘skeleton’? But this seems like a calculated effect in ‘Promises, Promises’, where, like the returning colonist struck by the signs of genetic dispersal, the reader is alerted to the minutest filaments of lexical kinship.

Muldoon once remarked that one of our most important authenticating factors is our belief in ‘another dimension, something around us and beyond us, which is our inheritance’. This ‘dimension’ seems to be the destination of the cast of disparus who feature throughout Muldoon’s corpus, each feat of disappearance hinting at an act of self-transcendence. In this context, the vanished colonists in ‘Promises, Promises’ belong with figures such as Brownlee from ‘Why Brownlee Left’ and ‘the pugilist-poet, Arthur Cravan’, who disappeared off the coast of Mexico in 1918. But the fascination with liminal and hybrid identities in the story of the Roanoke settlers also sets a precedent for the fantasies of colonial emigration satirised in his most eccentric work to date, ‘Madoc: A Mystery’. This long unwieldy piece is the polysituated poem par excellence, fitting elements of folklore, colonial history, biography, and speculative fiction into an edifice provided by the grand march of the Western intellect (the poem is divided into sections named after thinkers from ‘Thales’ to ‘Hawking’). While the main narrative thread follows Robert Southey and Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s fantastically abortive attempts to establish a Pantisocracy on the banks of the Susquehanna, the poem’s real tutelary spirit is Byron (who thrilled to the thought of being ‘redde on the banks of the Ohio’). There’s a Byronic swagger about Muldoon’s verse storytelling that has much to do with a self-conscious delight in doggerel: ‘Pike, pickerel. Hog, hoggerel. / Cock, cockerel. Dog, doggerel.’ These lines encode a joke about vulgarised forms of Latin (in its ‘pig’ or ‘dog’ varieties) that takes the characteristically Muldoonian form of a declension exercise. But there’s something here, too, about the dissolute doggerel artist whose appetite for combinatorial play offers up some mocking echo of the catechisms of the imperial tongue.

The emphasis given to the ludic qualities of Muldoon’s verse has tended to obscure the political implications of his mongrel tactics. Dislocations is decidedly pitched against ‘those who might still cast him as a lyrical purist who “plays” with language’. The way in which Muldoon ranges across English, Latin, Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Algonquian, and Narragansett tends to put purity beyond the pale. And for all the madcap antics that ensue in ‘Madoc’, the re-staging of historical claims to priority, indigeneity, and ownership have a bearing on the legacies of colonial and sectarian violence in not only North America but also Northern Ireland. If polysituatedness describes the utopian dimensions of Muldoon’s work (‘emblematic / of the desire to go beyond ourselves’), it also points ineffaceably to its emergence out of a colonial condition.

Comments powered by CComment