- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: An assured place

- Article Subtitle: Australia’s pre-eminent formalist

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Stephen Edgar, over the past two decades or so, has earned himself an assured place in contemporary Australian poetry (even in English-language poetry more generally) as its pre-eminent and most consistent formalist. His seemingly effortless poems appear in substantial overseas journals, reminding readers that rhyme and traditional metre have definitely not outlived their usefulness.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

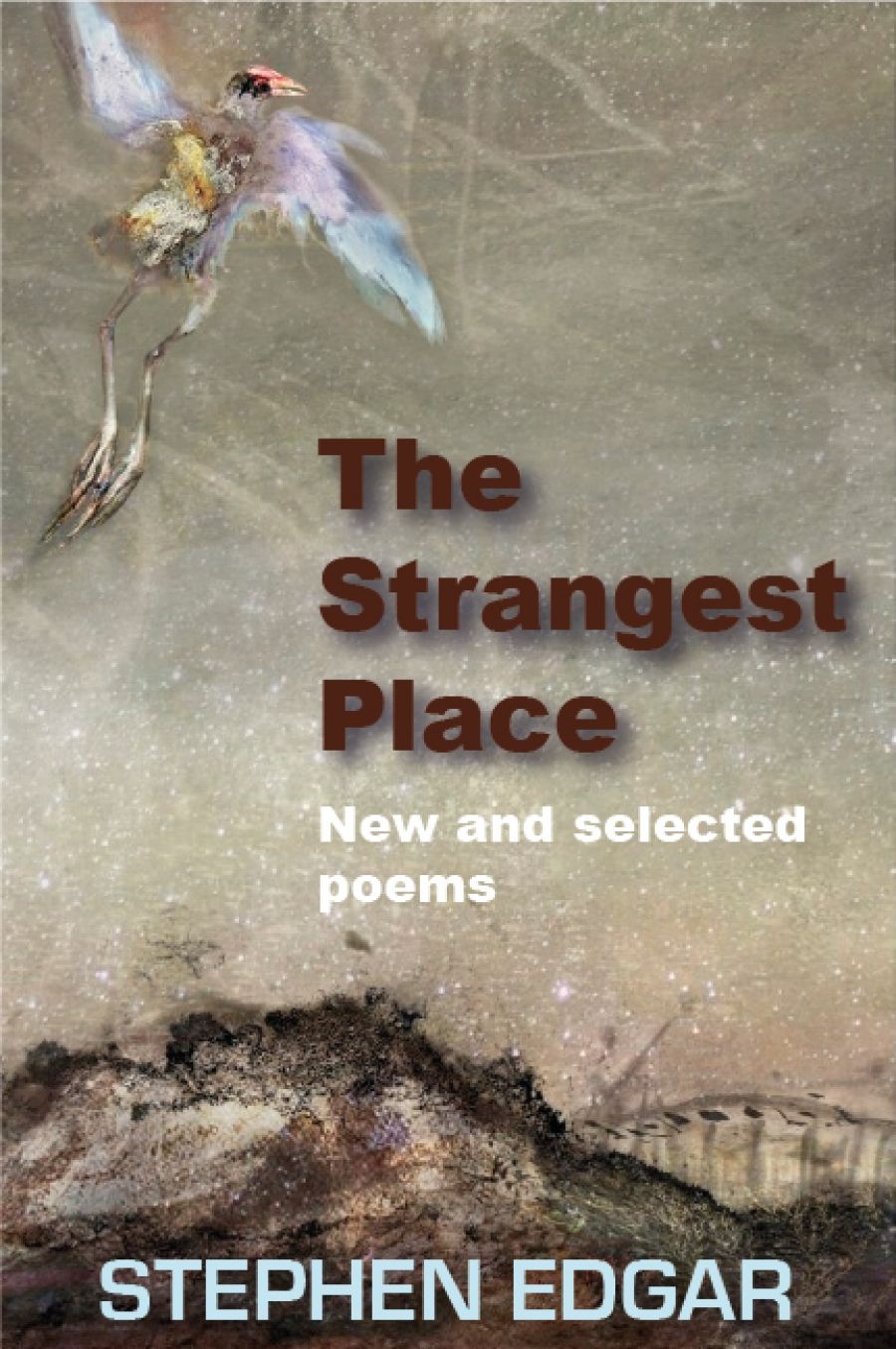

- Book 1 Title: The Strangest Place

- Book 1 Subtitle: New and selected poems

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Pepper, $29 pb, 302 pp

Edgar’s next two books, Corrupted Treasures (1995) and Where the Trees Were (1999) feature a number of highly memorable poems: ‘The Secret Life of Books’, ‘Daisy, Belle and Arthur’, and ‘Penshurst’, to name three. All of these have the vividness of Edgar’s best poetry from Lost in the Foreground (2003) onwards.

It is worth pausing here for a moment to consider the virtues and limitations of closely rhymed and metred verse when free verse is available as an alternative. Free verse can have a directness and rhetorical (even metaphorical) energy that highly formal poetry often lacks. Tightly rhymed poems (even when as subtle as Edgar’s) can occasionally have an ‘ingenious’ quality about them, where the reader is paying more attention to the technique than to the ‘substance’ of the poem. They can also involve complex syntax that can sound more like a legal argument than an outburst of lyricism. The reader’s reward for successfully negotiating such a poem may have more in common with the successful completion of a Times Literary Supplement crossword than with the ‘spontaneous overflow of emotion, recollected in tranquillity’ of which Wordsworth spoke.

It is interesting that in this context Edgar’s most ‘typical’ poems are not those that stay in the reader’s mind longest. The default ones tend to be clever and persuasive descriptions of weather (wind, in particular) or of estuarine or marine vistas. The final lines of ‘Summer’ are a reasonable example: ‘Almost without / A cloud, the unimagined sky annuls / All qualms across the bay’s embellishment / Which it exults above – except, far out, / A white dismay among the feeding gulls.’

Of course, taking an excerpt such as this from an almost fifty-line poem is hardly fair. It’s easy to appreciate, however, the sheer metaphorical energy of the ‘white dismay’ among the gulls and, likewise, the ‘unimagined’ sky that ‘annuls / All qualms’. So too the evocative and comprehensive imprecision of the ‘bay’s embellishment’. It should also be remembered that the ending here is a consolatory contrast to the boredom and monotony suffered by hospital patients earlier in the poem. ‘The drinking vessels and the get-well cards / Again, again the faces drained of hours, / Emptied by their waiting even of boredom, // Subsisting in their realm of four o’clock.’ In ‘Summer’, it’s more than obvious we are in the hands of a highly skilled poet, and that’s a good place to be at any time.

It is even more satisfying, however, to read a smaller number of unforgettable Edgar poems that focus on something outside the poet’s usual sensibility. Poems of this degree are most often encountered in Lost in the Foreground (2003), Other Summers (2006), and History of the Day (2009). They involve suffering (or a postlude or prelude to suffering) in other countries and times. Interestingly, they also involve ekphrastic accounts of photographic images. Three stand out: ‘Sun Pictorial’, ‘Living Colour’, and ‘Memorial’.

‘Sun Pictorial’ deals with how many of Mathew Brady’s photographic plates of the US Civil War were afterwards used to build greenhouses. Earlier in his poem, Edgar evokes the conflict’s ‘gauche onset / Of murderously clumsy troops, / Dismemberment by cannon’, before concluding with how the sun each day ensured the soldiers’ ‘ordered histories of the war / Were wiped to just clear glass and what the crops transpired’.

More telling still is Edgar’s account of recently discovered footage from pre-World War II Munich. ‘In colour too, / As bright and vivid as delirium. / It seems a kind of fault / In history and nature to restore / This Munich underneath the flawless blue // Of mid-July in nineteen thirty-nine, / This pageantry of party-coloured kitsch. / The Fuehrer, with his bored assessing gaze ...’

A third example is ‘Memorial’, a careful scrutiny of the well-known photograph ‘The lynching of Rubin Stacy, 19 July 1935’. After a more general description of the crowd, Edgar zooms in on ‘A girl of twelve, maybe, too unaware / To mask her downward grin’ before, at the poem’s end, moving on to: ‘The days that have to be the day that’s been, / Lighting forever everything she knows / With what she saw, and knows she saw, and knew.’ It is poems of this subtlety and drama that, for this reader, are the highpoint of Edgar’s career. What then of the book’s opening section, ‘Background Noise: New Poems’?

There’s no doubt that Edgar’s technical standards here are maintained, or even extended a little. The observation is just as sharp and cleverly rendered as usual, but there are not many poems as gripping (or distressing) as the ones just referenced. The poems here are often philosophical, concerned with ‘background’ issues such as the nature of time and our place in the cosmos. Occasionally, there is a more personal (though hardly confessional) poem that has a more emotional than speculative thrust. ‘Possession’ is one example – where the poet is clearing out the house of a recently deceased old woman, almost certainly his mother. He tells of how: ‘We emptied out the lot, / Some to distribute, much though to discard. / And so she was herself, after that stroke, / Emptied out: for four years there is not / One thing she owned that is not torn away.’

The Strangest Place thoroughly justifies Edgar’s impressive poetic reputation. He certainly does have the formal control and poise of which people speak. And in addition, from time to time, without warning, he can move you very deeply.

Comments powered by CComment