- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Environmental Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Looking away

- Article Subtitle: Balancing horror and hope amid a changing climate

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

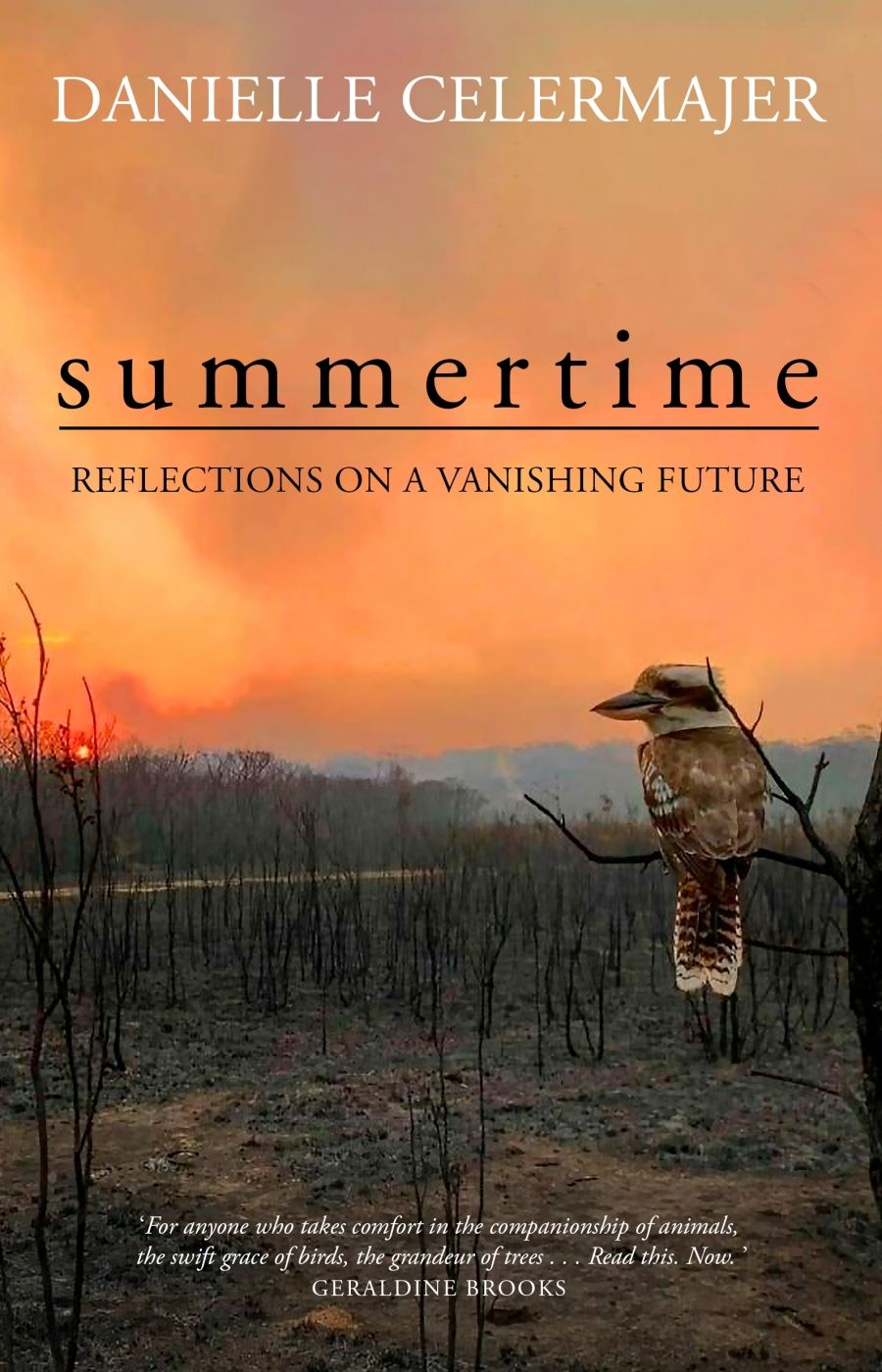

It’s an achievement to write about the climate crisis – and the resulting increase in Australian firestorms – without having people turn away to avoid their mounting ecological unease. Despite experiencing the Black Saturday bushfires of 2009 directly, I too am guilty of looking away. It’s easier that way. Danielle Celermajer, however, excels at both holding our attention and holding us to account, balancing the horror and hope of not-so-natural disasters, specifically extreme Australian bushfires, in her new book of narrative non-fiction, Summertime.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: Summertime

- Book 1 Subtitle: Reflections on a vanishing future

- Book 1 Biblio: Hamish Hamilton, $24.99 pb, 208 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/Ao0an1

Fuelled by the changing climate, the 2019–20 Australian bushfire season killed thirty-three people directly and more than 450 others from smoke-related illnesses. The fires, almost unimaginable in scale, killed more than three billion animals. One of these animals was Celermajer’s factory-farm-rescued pig Katy. We are introduced to Katy through the eyes of Jimmy, Calermajer’s surviving rescue pig, a symbol of hope for the New South Wales community in the firestorm’s aftermath. Found huddled in a muddy river, Jimmy had a ‘broken but miraculous presence’ when rescued for a second time. Jimmy’s story could have just been that – a happy news story of unlikely survival.

Building and cars burnt during bushfires in Australia, 2020 (murbansky/Alamy)

Building and cars burnt during bushfires in Australia, 2020 (murbansky/Alamy)

Celermajer, however, is careful not to reduce the story to a narrative loved by the media – with Jimmy the Pig symbolising hope among the ashes. Some will remember the viral image from Black Saturday of a dehydrated koala drinking from a firefighter’s plastic water bottle. Many wouldn’t know that this koala – named ‘Sam the Survivor’ by the press – died soon after. Some Australians love these comforting images, but many of us might not know, or want to know, the real stories behind them. Celermajer uses her pigs Jimmy and Katy to offer a much more nuanced narrative than the typical recovery story, which has become less relevant as the world’s disasters increase, in frequency and intensity, due to the climate crisis.

Celermajer’s pigs act as narrative bookends, highlighting her academic work on multispecies justice. Though not a new ploy, the author’s use of animals to tell a political story is mostly effective. If, at times, some of the animals in the book feel too anthropomorphised, the overarching message is ultimately strengthened by the author’s gentle connection with the animals around her, so many threatened by the quickly escalating climate crisis.

Celermajer is a professor of sociology and social policy at the University of Sydney. Her body of work reminds us that all animals, not just human ones, need Earth’s resources for survival. With humans, particularly wealthy Westerners, accelerating ecological collapse, Summertime shows the reader what’s at stake and where accountability lands. In one of Celermajer’s more confronting paragraphs, she writes with a brutal directness of the violence that bushfires inflict on animals: ‘The vets have told me about animals who, although burned, survived for a few days until their flesh started to fall off, and only then did they die.’

Celermajer writes, ‘In these pages I have written on the death of animals, of trees, of ecosystems and of summertime.’ Summertime, the book’s characteristically straightforward title, is itself a nod to the climate emergency and to the future reduction of the seasons into one endless, unendurable summer.

Many have noted that media coverage of the Black Summer was quickly sidelined by news of the unfolding Covid-19 pandemic in March 2020, causing the lengthy aftermath of Australia’s largest bushfire disaster to fade from view. Summertime successfully counteracts this and ensures that these stories of bushfire aftermath – of confusion, depression, and a small amount of hope – are not forgotten.

At its best, Celermajer’s imagery is poetic yet economical. She allows the reader to recognise the urgency of the climate disaster without feeling overwhelmed. Her likening of New South Wales’s bushfire skies to ‘the colour of an old bruise’ will resonate with anyone who watched the early media coverage of the fires. ‘The sky is a colour I have not seen before,’ Celermajer writes, remembering how she felt as the fire approached, highlighting simply yet powerfully how we are all hurtling towards the end of a habitable world – a perpetual and apocalyptic summer.

This sense of urgency about the unfolding climate crisis is at the core of Summertime. Celermajer’s frank observations are refreshingly clear and hopeful; we are forced to reflect on the damage already caused. Her work spotlights the link between extreme bushfire and human-caused temperature increases, a connection that was only heard faintly after Black Saturday.

Having written about bushfire and its aftermath at length, I have thought a lot about how quickly we forget – even if we’ve experienced the climate crisis firsthand – and about how this is propelling us towards ecological collapse. Twelve years after Black Saturday, I have almost forgotten the smell of our burning house; our chooks, charred and gasping; or, for years after, our community’s sense of confusion and loss. Summertime’s deceptively simple prose makes me remember with renewed urgency that it’s our collective shying from the horrors of the climate emergency that is fuelling the unfolding disaster.

The phrase ‘essential reading’ is a commonplace, but Summertime is just that – an awakening.

Comments powered by CComment