- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The ballet boy

- Article Subtitle: A candid memoir from David McAllister

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

David McAllister, known affectionately as ‘Daisy’ to his fellow dancers, completed this memoir just as Covid-19 put paid to the exciting program he had devised for his final year as artistic director of the Australian Ballet. In spite of the cancelled world premières, McAllister makes no complaint about what must surely have been a disappointing finale to a stellar career, but he remains upbeat, turning his hand to modest ‘Dancing with David’ videos, alongside the company’s filmed performances and the Bodytorque.Digital program.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

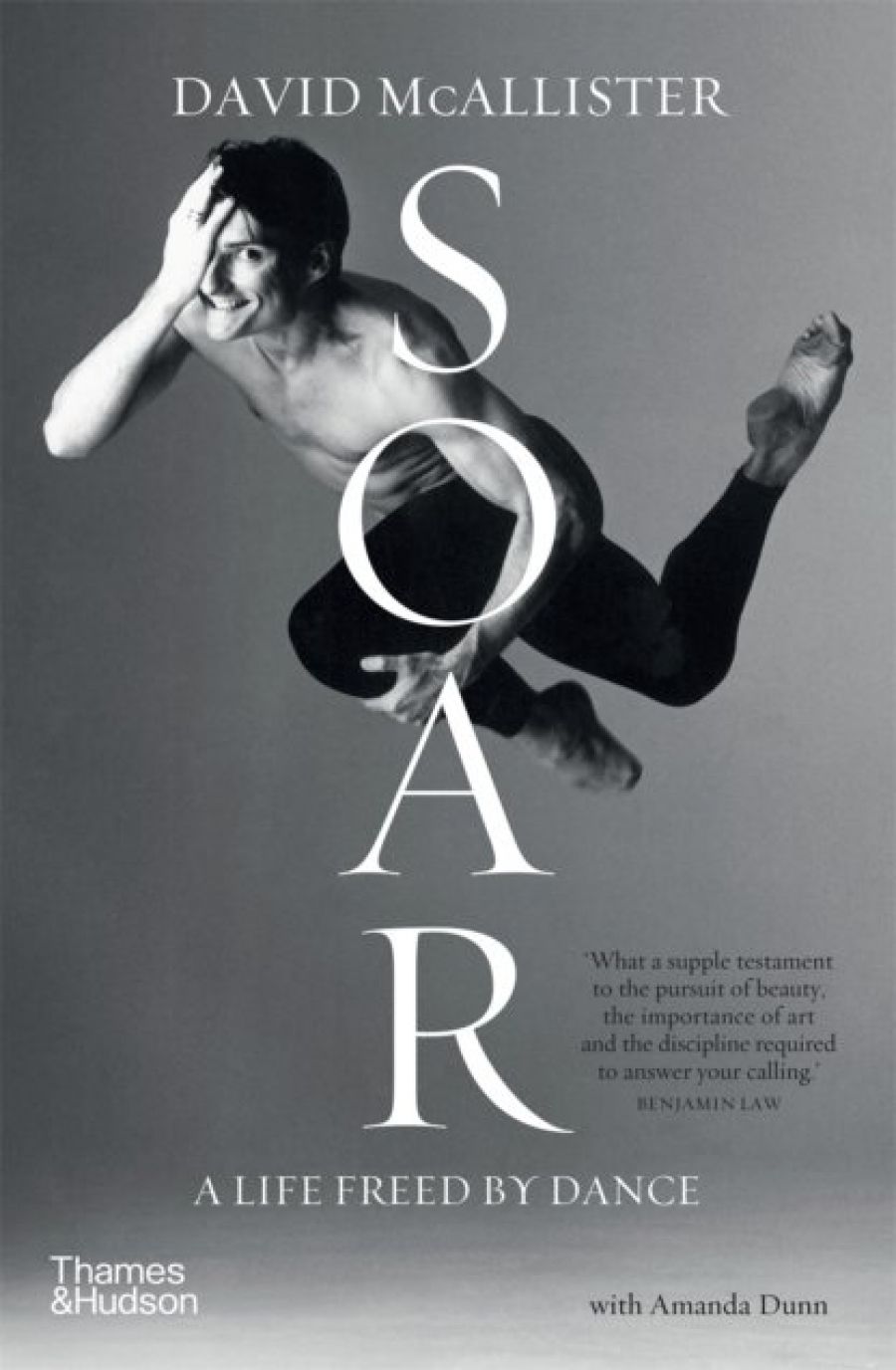

- Book 1 Title: Soar

- Book 1 Subtitle: A life freed by dance

- Book 1 Biblio: Thames & Hudson, $39.99 hb, 247 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/BqzXq

Born in 1963 and growing up as the middle child of five in the western suburbs of Perth, McAllister was on a daily mission to win attention. ‘Theatrical, stubborn and given to tantrums’, he pestered his parents to let him learn ballet. The deciding moment came when he was seven, sitting around the television with his family, watching the superstars Rudolf Nureyev and Margot Fonteyn performing the grand pas de deux from Don Quixote. His parents enrolled him in Miss Hodgkinson’s class, with thirty little girls. Known as ‘the ballet boy’, he ran the gauntlet of the schoolyard bullies to homophobic insults. He didn’t know what the words meant, but he felt their sting.

The obstacles kept looming in his path, not least his fears that he was too short, had footballer’s legs and a big nose, and lacked the physical grace of the fairytale prince in the classical repertoire. He never lost those fears but set his course early and would not be deviated from it. ‘One day I’ll be famous, and that will be my revenge.’ By his own admission, he was more Mercutio than Romeo, but talent and hard work elevated him to the princely roles of Romeo, Siegfried, and Albrecht.

McAllister writes with a light touch, humility, and a keen eye for detail: his mother’s rotating dinner menu in the 1960s, her 1970s gold and teal decor, and the domestic bliss of his current life with the departing director of the Sydney Festival, Wesley Enoch, with McAllister playing ‘Lord of the Laundry’ to Enoch’s MasterChef.

McAllister gives a clear account of his dancing injuries, but is less effective in evoking the joy of dancing, of what it feels like to take flight across the stage. He comes closest in the chapter devoted to his participation in the 1985 Moscow International Ballet Competition, where he won a bronze medal, dancing with his long-term partner Elizabeth Toohey. He conveys the gruelling preparation, the excitement of the three-round knockout, the enthusiasm of the Russian audience, and the miracles the body can perform, despite injuries. This success is sealed by an invitation, beyond his wildest dreams, to return to Moscow to dance with the Bolshoi Ballet.

By the beginning of 2000, when McAllister was contemplating his retirement from dancing into management or teaching, the position of artistic director became vacant. He astonished himself and delighted his fellow dancers by landing the job. In preparation, he met up with artistic directors around the world, where he broadened his vision for the role, setting in motion fruitful collaborations with choreographers.

McAllister’s tenure has seen many changes in the running of the company, particularly in the care of the dancers. He has appointed dancers who do not fit the classical mould in body or ethnic type; he also encourages healthy eating, Pilates strengthening, and a general outward focus on the world, rather than the élitist and exclusive mindset of traditional ballet. Female dancers are given extended maternity leave and are welcomed back into the company soon after giving birth.

McAllister is clearly a people-pleaser who avoids conflict and is somewhat risk-averse. He admits this may have been his weakness as artistic director, but he defends his decision to make the Australian Ballet commercially successful, keeping audiences happy and giving scope for creative innovation among the dancers. His ‘good boy genes’ are evident throughout the memoir in the even-handed and generous approach in which he pays tribute to his ballerinas, mentors, and colleagues.

Soar sits at the confluence of memoir and autobiography. As a memoir, it has twin themes: a boy obsessed with ballet who, against all odds, achieves his ambition to be a principal dancer, and a man who finally achieves peace of mind when he embraces his sexuality in his forties. Held together by these overriding themes, the book is also a stage-by-stage account of a career in dance and the history of the Australian Ballet over the past forty years. It contributes a valuable personal record to the historical documentation of the Australian Ballet.

The book is co-authored by journalist Amanda Dunn, who encouraged McAllister to write a memoir and structured it around his personal anecdotes. Soar is a seamless work, with McAllister’s voice at the heart, revealing the author’s humour and optimism. From the stylish cover, with its images of the puckish McAllister in full flight to the comprehensive pages of acknowledgments, it is a reflection of an articulate public figure and a man of integrity. What is surprising, after decades of maintaining his privacy, are the candid revelations about his intimate relationships and his sexuality. It is heartening to discover the fairytale career has a happy ending, both onstage and off.

Comments powered by CComment