- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A promised gift

- Article Subtitle: Revisiting a short-lived prodigy

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

David Frith’s slim biography of Archie Jackson reflects his subject’s tragically short life. When Jackson made his Test match début for Australia at Adelaide in the 1928–29 Ashes series, scoring an eye-catching 164, it was he, rather than the young Don Bradman, who instilled the most excitement in this country’s cricket-loving public. When Jackson was included in the 1930 tour of England, one ex-cricketer, Cecil Parkin, remarked that he was ‘a better bat than Bradman’, who had débuted in the same series as Jackson. This is but one example of the lavish praise that the gifted, though inconsistent, young cricketer received during his lifetime.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: Archie Jackson

- Book 1 Subtitle: Cricket’s tragic genius

- Book 1 Biblio: Slattery Media Group, $29.95 hb, 151 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/ALyo7

In February 1933, Jackson died of tuberculosis aged just twenty-three, after years of questionable health and having played only eight Tests. Archie Jackson: Cricket’s tragic genius laments what might have been had Jackson lived longer. The book memorialises its subject, a player whose funeral attracted a sad sea of mourners akin to that which attended the great Victor Trumper’s in 1915. Frith, whose expansive cricket bibliography extends back over fifty years, has long contemplated and admired Jackson: this book, now revised and updated, was first published in 1974. Jackson possessed what Frith calls a ‘promised gift’. His ‘delicate artistry’ with the bat, alongside his warm and good-spirited personality, endeared him to fellow players and the public alike.

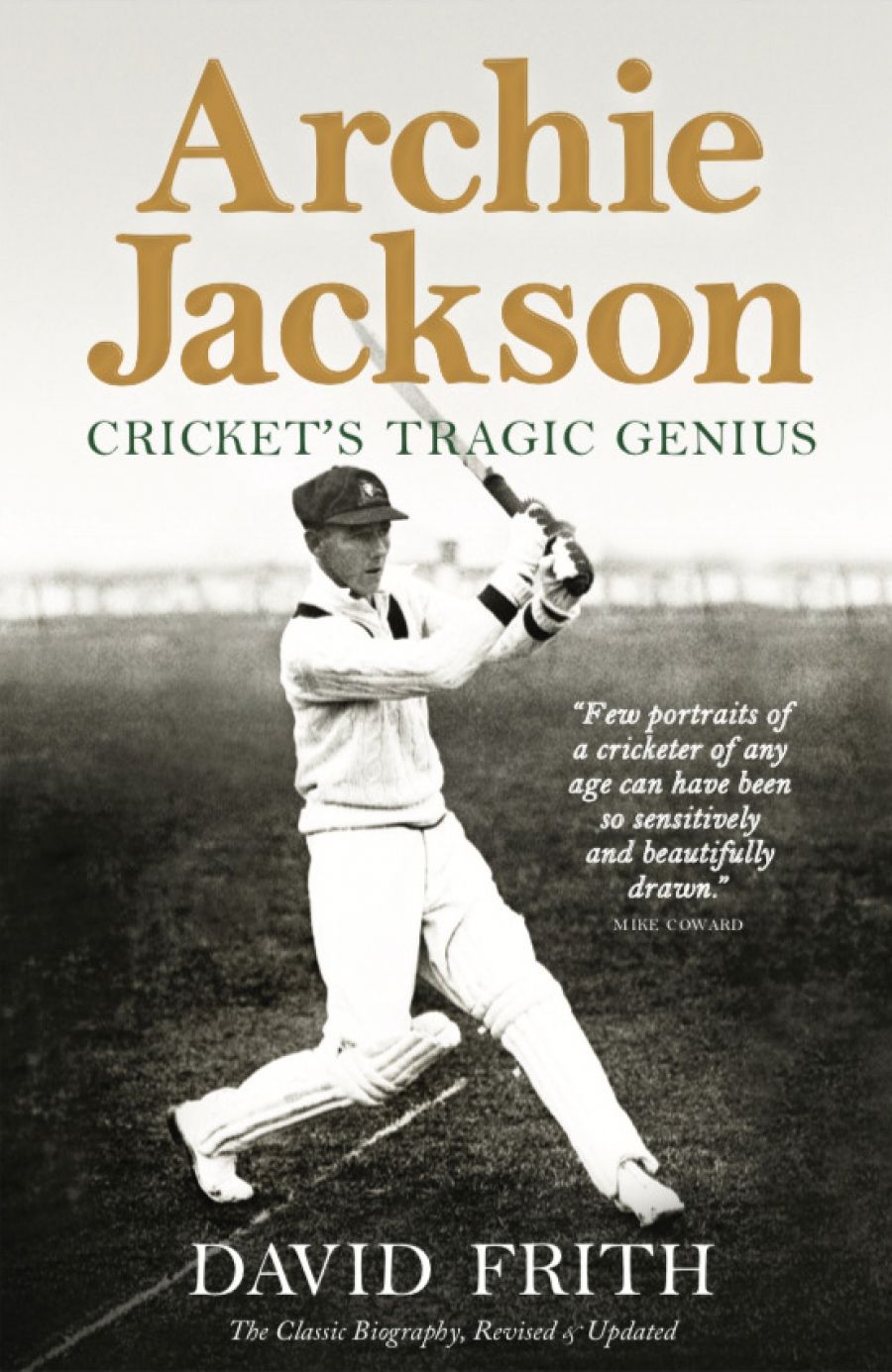

Australian cricketer Archie Jackson wearing a 'baggy blue' New South Wales cap (Fairfax/Wikimedia Commons)

Australian cricketer Archie Jackson wearing a 'baggy blue' New South Wales cap (Fairfax/Wikimedia Commons)

Jackson, however, is lost to all but the most ardent cricket aficionados today. There is no recording of his voice, only a small supply of footage of him at the crease, and it is all too easy to overlook his achievements in the wake of the dominant presence of Don Bradman in the 1930s and 1940s. He belongs, in essence, to another time. Cricket is a game so dominated by numbers and statistics that many players of bygone eras, particularly those who played before matches were televised, are doomed to be remembered or judged only by a cursory glance over their averages. To bring Jackson’s story into the light, Frith relies primarily on an impressive array of oral testimony, gathered largely by the author himself prior to the book’s initial publication, from those who knew Jackson, alongside contemporary written accounts. The richness of these sources, which come from close family members, friends, journalists, and others who met Jackson, allows Frith to reach beyond the numbers and to retrieve the man himself. This is, of course, what any good sporting biography should strive to do.

Consider, for example, one story involving Alec Marks, a teammate of Jackson’s for New South Wales. During a match at the Sydney Cricket Ground in 1929, Jackson borrowed a towel from Marks but failed to return it at the close of play. Rather than returning the towel next day, Jackson proffered a brand new one (which was deemed inferior by Marks’s mother) with no explanation. Marks did not find out why this was until he visited Jackson as he lay dying in hospital just over three years later. Jackson already knew by this stage that he had a serious illness and had borrowed the towel without thinking. Fearing that he might have contaminated it, but not wanting to reveal the nature of his illness, he thought it best to buy a new one. When Marks returned from the hospital, he found the towel and cried into it. The humanity of Jackson similarly shines when we find him coughing up blood following a club game towards the end of his life. Despite being in severe pain and too exhausted to remove his own pads, he still found time to sign an autograph for a young fan in the dressing room.

The book is illuminated with such tales of Jackson’s humanity. This makes it all the more troubling to read about his final months as tuberculosis ravaged his body. To Frith, Jackson is ‘the first tragic hero of Australian cricket’, perhaps even more tragic than Victor Trumper. Trumper, the great Australian batsman of cricket’s Golden Age, died as a result of Bright’s disease aged thirty-seven in 1915, a year when the Australian national community would begin to come to terms with lost youth on a far more tragic scale. Cricket lovers had, however, been able to see him in his majestic prime. By the time he ended his career, he had played in forty-eight Tests and scored forty-two first-class centuries. In Jackson, those who had marvelled at Trumper’s feats believed that they had found his spiritual heir. There is no telling what Jackson might have achieved had he lived. Frith poignantly captures this sense of loss, not only to the game, but to the legions of fans who attended the Sydney Cricket Ground on summer afternoons to watch Jackson and other iconic players, to a wide circle of friends and family who adored the young man, and to his fiancée, Phyllis, to whom Jackson had become engaged days before his death.

There are certain idiosyncrasies in Frith’s writing. If a ship that once carried Jackson and his teammates later sank, he is sure to inform the reader. Discussing a game between New South Wales and the Marylebone Cricket Club in February 1929, he strangely notes that the match began ‘the day after the St Valentine’s Day Massacre in faraway Chicago’. These minor quibbles, however, do not distract from what is an impeccably researched and moving portrait of a young man who clearly had so much more to give. Far more than numbers on yellowed scorecards, Jackson’s story is a reminder of how sportsmen and women can capture our imagination, and also of just how cruel life can be.

Comments powered by CComment