- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

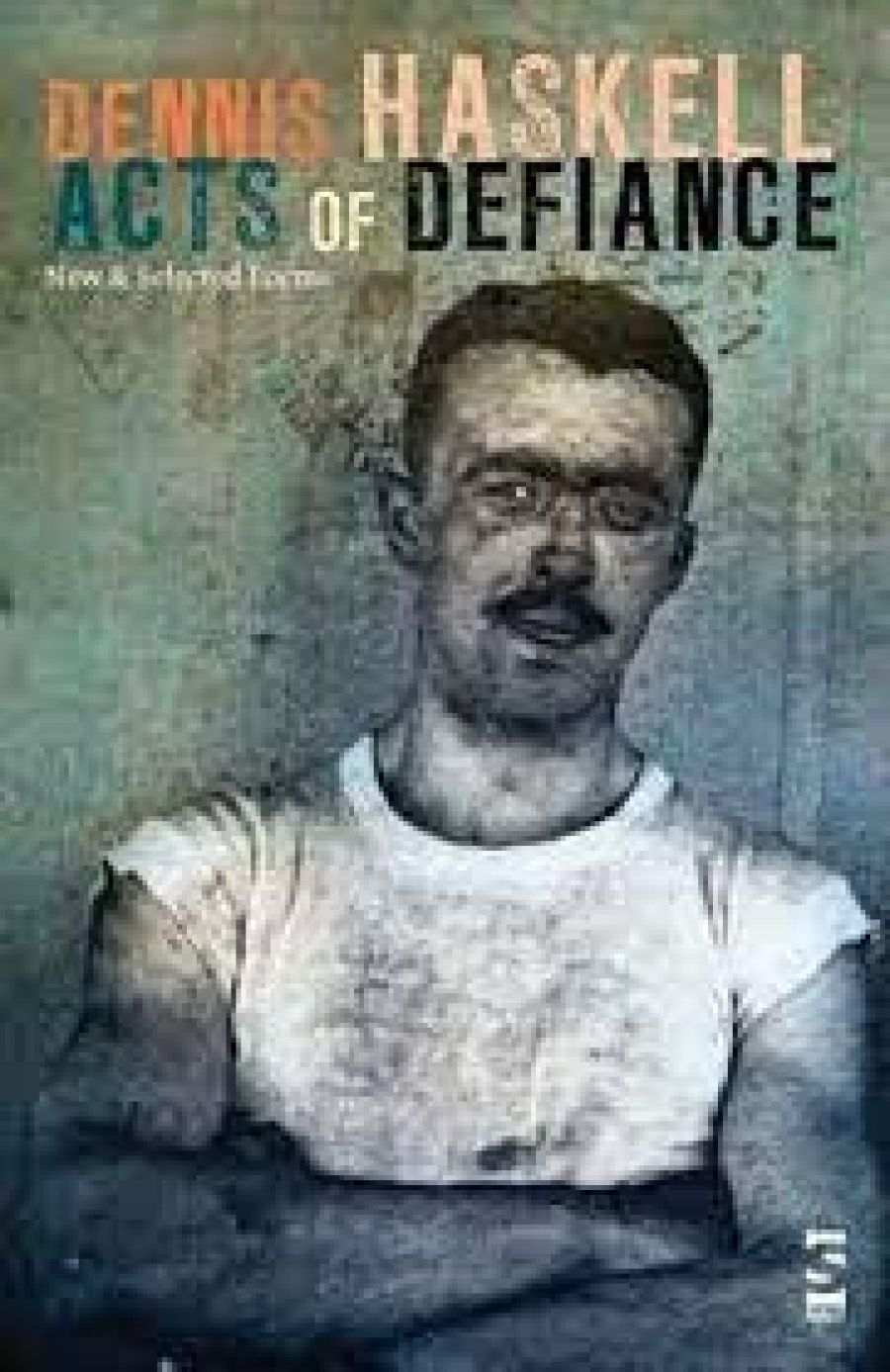

- Custom Article Title: Martin Duwell reviews 'Acts of Defiance: New and Selected Poems' by Dennis Haskell

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

First books often suffer most in a Selected Poems as the poet who finally emerges from the possibilities explored in the poems of the first book retrospectively weeds out those poems that are not in what becomes the dominant mode. This certainly happens in the case of Dennis Haskell’s Acts of Defiance ...

- Book 1 Title: Acts of Defiance

- Book 1 Subtitle: New and selected poems

- Book 1 Biblio: Salt Publishing (Inbooks) $24.95 pb, 142 pp

By the time of his second book, Abracadabra(1993), Haskell seems to have settled into the kind of poet he is going to be. This won’t be a poetry of the transcendental or of the visionary. It certainly won’t be the poetry of large statements of any kind. It will be the poetry of personal experience, meditated on. In other words, humane, thoughtful, intelligent. You can tell that Haskell feels that this may need some defence, because Abracadabra begins with a quotation from Michael Wilding (drawn, incidentally, from Australian Book Review), in which Wilding speaks of the necessity of not separating life into meaningful passages interspersed with long humdrum periods of ‘everyday labour’. Itcontains poems such as ‘Late Letter’, in which Haskell praises a friend who, he says, convinced him ‘not to be frightened / of life’s littleness, / to value the ordinary, / to see the grand / pomposity of literature / for what it is, to laugh’.

Abracadabra begins with what turns out to be a repetitive image throughout Haskell’s poetry: that of flying; the humdrum everyday experience of the academic. If Slessor’s central position is that of looking through glass into another reality, then Haskell’s is that of sitting in an aeroplane, that experience of seeming to be stationary in a tin tube while in fact moving very quickly. For him this seems to induce the meditative state of ‘curiously involved detachment’ (to quote another poem rather out of context) required for his poetry.

In the title poem of Abracadabra, flight is made an analogy for life in Perth, in that both induce a sense of an alien reality. From the air, clouds appear to be ‘flimsy // thick airborne snow’, but on earth the quintessentially postmodern city of Perth, built nowhere and on nothing, is equally weird. As another poem says, ‘to take off is to forfeit your perspectives // to technology as epic as the passivity / it foists upon us’. Flying can also represent, as it does in ‘Reality’s Conquests’, the remote perspective that produces abstract generalisations about other cultures. It is a position from which ‘all is theory / that somehow doesn’t work’, where ‘everything is quite right, and nothing quite real’.

Above all, flying allows Haskell to dwell on the idea of process. ‘Constancy’, a poem about Canberra, says that, ‘to be alive / is to be moving / away from where we are, / even in sleep’, and many of the poems in this book express a dislike for settled positions both physically and intellectually: ‘To live a life without self-doubt / is a terrible thing.’ ‘That World Whose Sanity We Know’ has the poet recalling, while flying, the experience of sharing a train with a book by Derek Mahon ‘who has hardly grasped what life is about’ and with two Christians who have no doubts at all as to what it is about.

One of the book’s best poems takes its title, ‘Writ in Water’, from Keats but is about the experience of travelling in Germany and seeing the Rhine from the famous mountaintop perspective that is the embodiment of the classic tourist’s view. But the poem is really about the selves of the travellers who move through a language and reality that is not theirs. The result is an image of these selves, not as strong Aussie personalities, but as temporary phantasms:

And on the river’s

slate surface, on a road

not a road, certainly not taken,

in a land that is not ours,

I could almost discern

something, like our names, writ in

water,

and almost begin to read its meaning.

This desire to read meaning and to understand something of its complexities lies behind a collection of poems that might otherwise seem to be no more than the meditations of a well-heeled flyer. The book’s title derives from the assertion that ‘each attempt / at meaning is an act / of defiance of death’. I think the poems in this book slowly win you over. They aren’t comfortable essayistic meditations, but worried wrestlings with life itself, seen as process. One of the new poems, a kind of version of Slessor’s ‘The Night-Ride’, asks ‘What are you doing here / racing through the uncontrolled landscape / of your life?’ It is a seriously felt, seriously posed, question.

Comments powered by CComment