- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Vanished festivities

- Article Subtitle: An examination of trespass and landscape

- Custom Highlight Text:

The concept of ‘trespass’ first entered English law records in the thirteenth century. That this appearance fell between the arrival of William the Conqueror in 1066 and the reformation of the English church by Henry VIII in 1534 is no accident. As Nick Hayes shows in The Book of Trespass, the process by which the English commons were enclosed by the statutes of the wealthy landowning class was slow but resolute; and it had everything to do with, on the one hand, the arrival of Norman delineations of property and, on the other, the disbanding of the monasteries that had worked in a bartering symbiosis with the people of the common landscapes of England.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

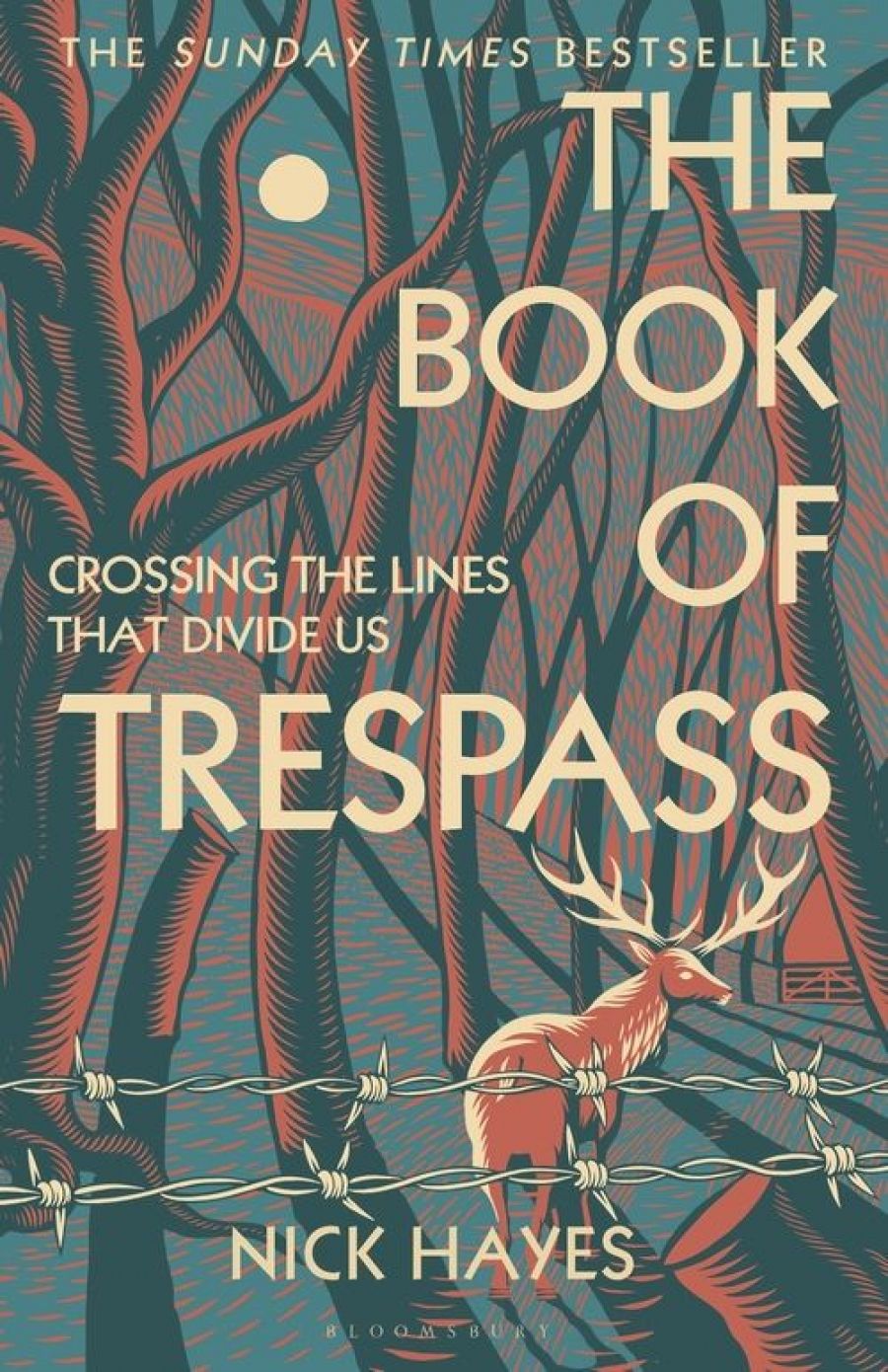

- Book 1 Title: The Book of Trespass

- Book 1 Subtitle: Crossing the lines that divide us

- Book 1 Biblio: Bloomsbury, $36.99 pb, 464 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/eyEeZ

Thus Hayes chronicles the criminalisation of the landscape via a thorough interrogation of the apparatus and nomenclature of class. He grounds his litany of exhaustive research with tales of his own trespasses, by foot and kayak, onto the major aristocratic estates of England. Each chapter is framed by Hayes venturing into one or other forbidden zone of exclusionary power, where, as he writes, ‘the woods felt like an empty marquee, hushed, the party long gone’.

This sense of a vanished festivity permeates this book. Through Hayes’s lens, English culture was once not so different from pre-1788 Australia, a thesis specifically addressed by Boyce’s Imperial Mud. In their own ways, both books show how, through a series of land grabs facilitated by parliamentary cliques in their own favour, the cultural heartlands of old Albion were systematically stolen from its people.

That’s not to say that the population didn’t fight back. One of the strengths of Hayes’s account is his celebration of the various uprisings, protests, and rebellions that resisted and campaigned against the decline of England into its currently class-riven and sequestered state. These fightbacks were the forerunners to the Occupy Movement, Grow Heathrow, Extinction Rebellion, and other protests of trespass in our current day. By performing the useful function of accounting for this ongoing spirit of reclamation, Hayes points the way towards an unstitching of the expropriative corset that has tightened over his island.

Hayes is brilliant at using the language of power to illustrate the dubiousness of its own stolen prerogatives. His explorations into the etymology of various relevant words, including ‘trespass’ itself, shows the layering of presumption that has obscured the island’s formerly intervolved regional cultures. When he fails to elicit any real dramatic spice through his own illegal escapades, he bites the bullet and arranges a meeting with the largest private landowner in his own home region of West Berkshire, the former MP, Richard Benyon. Hayes finds this good-looking scion – controller of 12,332 acres – entirely charming until he begins to unravel some of this history for him. A metaphorical storm cloud passes over the formerly beneficent face and Hayes is left standing alone as this inheritor of the enclosed commons stomps off in umbrage at being told his own story and the story of his forebears.

As well as being a thorough, if at times sermonising, historian, Hayes is also an accomplished illustrator. Each chapter is adorned with visual representations of the scenes of his own trespasses. Interestingly, the faceted style of these linocuts is in itself highly structured, thereby proving that the natural desire for the right to roam – so often decried by the horses-and-hounds set as the anarchic yearning of something akin to Kenneth Grahame’s weasels – does not in any way have to destroy a refined cultural aesthetic perfectly in step with the analogue contours and retinal harmonies of the land. Hayes rightly points to countries such as Sweden, Iceland, Finland, and the Czech Republic, in which reciprocal use of the landscape is an intrinsic feature of nationhood. Indeed, across the border in Scotland are a set of roaming rules that Hayes abides by in each of his trespasses in the book, thus proving poet John Clare’s view that the abstract delineations of maps, and the rules that go with them, can turn a poet into a criminal at the stroke of a pen.

It is interesting to wonder whether what is often taken to be a natural inclination towards the pastoral and lyric in the history of English literature has in fact been seeded all along by the millions of acres of English natural space that have been lost, or as Hayes might say, pilfered, since the Norman invasion. With only eight per cent of England remaining accessible to the general population, the ancestral memory of these once-common lands lies limestone deep in the cultural psyche. It is probable that the sense of othering implied by the Romantic fetishisation of landscape has been intensified in compensation. Indeed, the ornamental mythology of hedgerow and skylark that still persists to the delight of many may well be even more nostalgic than we thought. Is it some kind of epigenetic manifestation inflected with a literary version of PTSD? The fact that the very best of England’s nature poets were seldom from the landowner families only adds weight to the theory.

Comments powered by CComment