- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Echoes

- Article Subtitle: The untold story of Mary Li

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

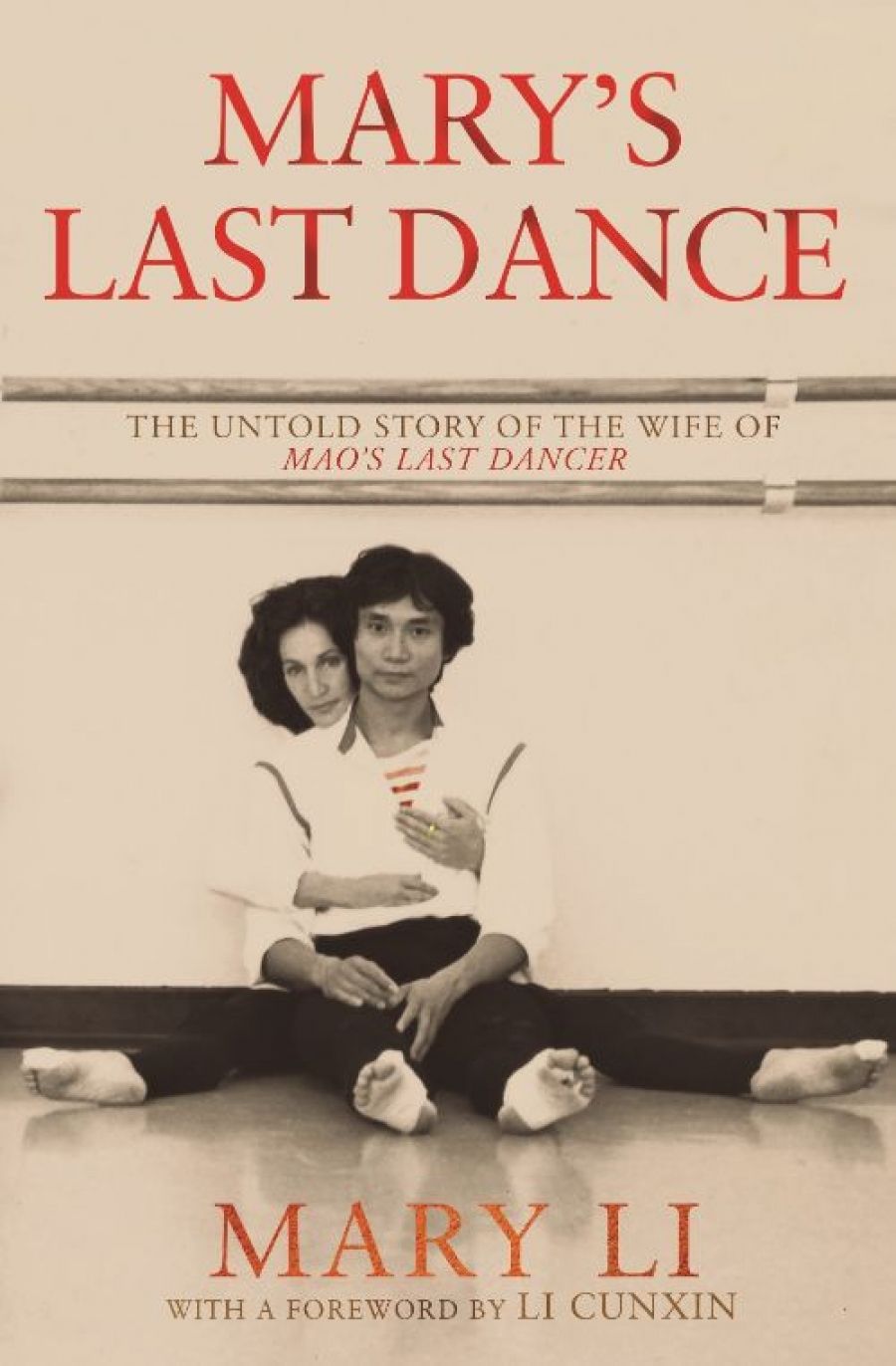

The cover of this book tells you pretty much what to expect. It shows the dancer Li Cunxin, evidently at rehearsal, facing the camera while over his shoulder peeps his wife, Mary. Add the subtitle, that this is the ‘untold story’ of Li Cunxin’s wife, with a foreword by the man himself, and it’s clear that this book might not have seen the light of day without the phenomenal success of Mao’s Last Dancer, published in 2003 and later made into a well-received film (Bruce Beresford, 2009). Even the title has echoes of its predecessor.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: Mary’s Last Dance

- Book 1 Subtitle: The untold story of the wife of Mao’s Last Dancer

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $34.99 pb, 472 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/36ZyA

The first part describes her early life and career. A member of a large family, Mary knew she wanted to devote her life to ballet very early. Helped by her parents – their role and support in her career are crucial elements in Mary’s story – she demonstrated great talent, tenacity, and determination. Aged sixteen, she won a scholarship to the Royal Ballet School. Life in London as a young ballet student was rewarding but very arduous. After a while, Mary left the school to join the London Festival Ballet, where she became a soloist and later principal dancer, before continuing her career in the United States for the Houston Ballet. It was there that she met Li Cunxin; they became partners on the stage and in life.

Mary Li (photograph by Mikala Connor/Penguin)

Mary Li (photograph by Mikala Connor/Penguin)

All this is recounted with a certain straightforward breeziness. There is very little here about the sheer backbreaking toil of working in ballet at this level. Mary Li provides a few telling details, such as the dancers’ need to arrange strips of cheap steak around their toes – cushioning against relentless blisters – before donning pointe shoes. She also mentions that her defection to the Houston Ballet fractured at least one important professional friendship. Ballet being such an extraordinarily difficult art form, it would also have been good to read about the camaraderie dancers share in making it all look so effortless. In any ballet company, as in any group of people working together, there must have been tensions of various kinds. A few brief pen portraits of celebrities Mary Li worked with – Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev, say – would have added some colour. Some discussion about the mechanics of a successful ballet partnership, such as Mary had with Li Cunxin (they were principals and partners in ballets such as Swan Lake and The Nutcracker), would have added depth too.

Mary Li writes at some length about her husband’s parents, known to readers from Mao’s Last Dancer; Li Cunxin gives a clear and often dismal picture of their life in Communist China. Mary mentions bad toilets and slum flats in Beijing, but little more.

This generally insouciant tone may result from Mary’s need to draw as great a contrast as possible between this part of her life and what came next. This was the devastating knowledge that her daughter Sophie was born profoundly deaf. Mary and Li were bluntly told that if they wanted to continue their careers as dancers, Sophie would probably never learn to speak. The last third of the book deals with the consequences of Mary’s decision to give up her beloved career to look after her daughter, channelling her formidable determination into helping Sophie learn to speak properly.

This is the most effective and emotionally satisfying part of the book. It is impossible not to sympathise with Sophie and her mother as they handled the years of speech therapy, interminable visits to specialists, frustrations, and occasional triumphs. The twist in this story comes at the end when Sophie, after many years and a great deal of hard work, declares that she does not entirely accept what her mother wants for her. Her letter to her parents about this is wrenching.

Mary Li has to cover a great deal of ground in this book, some of which will be known to readers of Mao’s Last Dancer. Perhaps her need to tell the complete story, to get everything down, accounts for its comparative lack of reflection. I wished, sometimes, that she had slowed down a bit and offered more vivid pictures of events in her remarkable career. Instead, performances are described as incredible, people as mostly wonderful, lives as having been changed forever.

Unmannerly though saying so might be, I also wished she had expressed just a little snappiness, frustration, even bad temper. Surely she must have resented being stuck at home, not working, while her husband went forth to conquer the world, first as a dancer, then as a successful stockbroker, and latterly as artistic director of the Queensland Ballet. Were there any cross-cultural strains in the marriage? How strongly did Mary embrace the culture she married into? Did she ever learn Mandarin? Some humour would also have been welcome.

But quibbling about the writing style in Mary’s Last Dance is probably churlish. What comes through is the importance of family: Mary’s love for her husband and children, the support of her own family, the affection of both Mary and Li for Li’s parents. Love of family is the core of this book, and as a paean to the value of hard work, friendship, and family values, Mary’s Last Dance works well. It should also sell its socks off.

Comments powered by CComment