- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Painting, punting, procreation

- Article Subtitle: A gargantuan life of Lucian Freud

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

To start with the broadest of generalisations, artists’ biographies can be divided into three types: those that concentrate on the work; those that take the life as their focus; and the ‘life and times’ volumes that attempt to place the artist in her social and political context.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: The Lives of Lucian Freud

- Book 1 Subtitle: Fame, 1968–2011

- Book 1 Biblio: Bloomsbury, $69.99 hb, 568 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/OV9PN

What Feaver has in fact produced are two volumes, the first entitled Youth (2019), the second, Fame. Youth is not so much a novel as a vast torrent of gossip through which Feaver’s determined subject single-mindedly steers his course. Freud seems to have met practically everyone in London, and practically everyone in London appears in the book. Names well known, half recognised, and completely unfamiliar waft by in such profusion that the publisher should have given us the sort of dramatis personae that used to be placed at the front of Russian novels, except that would have added yet more weight to this wrist-straining tome. At the very least, a family tree would have been useful to clarify which of Freud’s numerous acknowledged children was the product of which particular dalliance. Freud, when asked why so many of his children were of a similar age, is supposed to have replied, ‘Well, in those days I had a bicycle.’

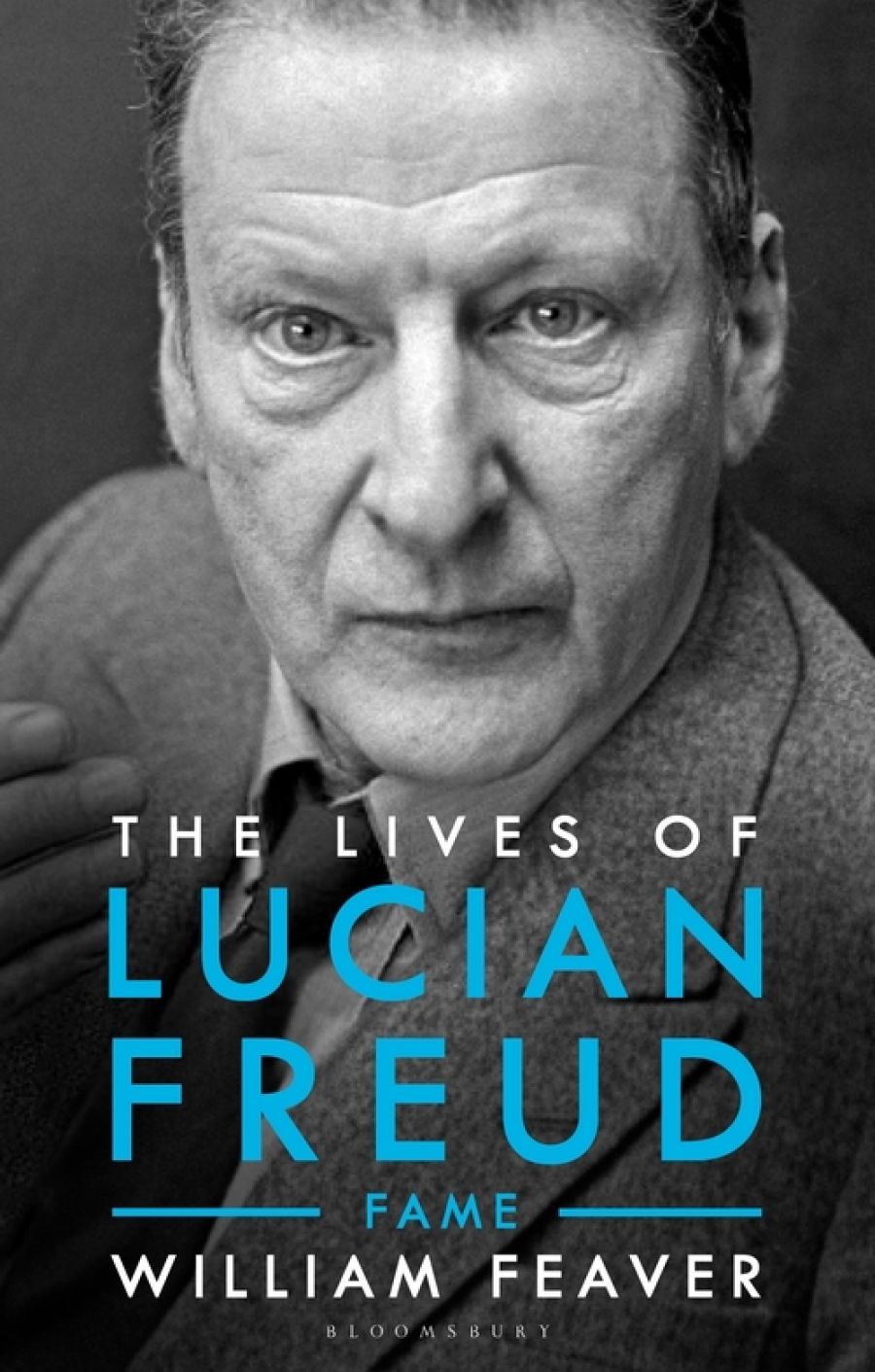

Lucian Freud at a private viewing of Lucian Freud exhibition at the Pompidou Centre in Paris, 2011 (EDB Image Archive/Alamy)

Lucian Freud at a private viewing of Lucian Freud exhibition at the Pompidou Centre in Paris, 2011 (EDB Image Archive/Alamy)

Youth deals with Freud’s relocation from Berlin to London at the age of ten and his somewhat fraught schooling. It covers Freud’s two early, brief marriages and his even briefer hapless wartime service as an ordinary seaman. Invalided out of the service, he was able to indulge in his lifelong obsessions: painting, punting, and procreation.

With the second volume, Fame, both Feaver and his subject have calmed down somewhat. The cast shrinks to Freud’s intimates, the gallery directors and dealers with whom he negotiates and feuds, and the sitters he cajoles into posing for him.

The book begins in the late 1960s. Freud is middle-aged and in mid-career. His jeunesse dorée years are over; his work being out of fashion, he is being treated if not dismissively then warily by the critics. A 1974 retrospective at the Hayward Gallery presented him as a mature artist with a solid body of work, but the critics were muted in their response. When the expatriate American painter R.B. Kitaj corralled him into his School of London, a grouping that included Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach, and Leon Kossoff, it at least gave the critics somewhere to place him. Freud himself was less than enthralled at being grouped with anyone and was delighted when Kitaj declared the School of London dead.

His reputation began to grow in the 1980s. A further retrospective in 1987 was greeted with disdain when offered to the major American galleries. Relegated to the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, it proved a surprise success and received glowing reviews. When it arrived at the Hayward, it clocked up the third-largest attendance to date after Dalí and Picasso. As Freud’s reputation grew, so did his prices. This caused a rift in his decades-long friendship with Bacon, who was not pleased to find himself with a rival in the Great British Figurative Painter stakes. The rift developed into a feud, with Freud describing his erstwhile friend’s later work as being like poor-imitation Bacon. Bacon, on the other hand, played the man by saying of Freud: ‘She’s left me after all this time. And she’s had all these children just to prove that she’s not homosexual.’

Freud’s children, in their late teens and early twenties, became useful in his perennial search for sitters, and he developed close relations with those he favoured. He developed even closer ones with some of their friends, who also sat for him. As he got older and the age gap grew between him and the muse of the moment, he became more obliging. When one young woman demanded a ‘Dukes dinner’, Freud rustled up three. His earlier social-climbing days proved useful. Later, in his seventies, he took an even younger protégée on a four-day jaunt to New York flying on the Concorde. ‘Frisky’ she called him, but one can think of other appropriate adjectives. In one of his late pictures, the disturbing The painter surprised by a naked admirer, the naked young model seated on the ground clutches Freud’s leg adoringly. Freud was impenitent: ‘people change. “Dirty bastard” becomes “Hey, he can still do it.”’ As Feaver puts it, ‘Basically each relationship was vital only so long as each painting required … People were drawn in, made to feel indispensable and when his attention moved on grievously put out.’

Freud may have been ageing, but until the very end there was little sign of it in the work. For Kitaj, Freud, ‘who was a wonderful painter’, became ‘a great painter between the ages of sixty and seventy’. Certainly, with the portraits of the Australian performance artist Leigh Bowery and his circle, confronting as they were to some, Freud was at the top of his game.

The final disintegration is sad. Feaver, who gradually becomes more of a presence throughout the book, depicts an increasingly confused old man desperately trying to finish his last works.

Although Feaver’s magnum opus could definitely have used a sterner editor, it is a memorable exploration of an extraordinary personality. Those who are prepared to give up a portion of their lives to work through it will be intrigued and amused by its depiction of a man whom the perceptive Auerbach described as ‘the most focused and unshowy and concentrated painter you could imagine’. A man ‘who was more nervous and alive than other people … also more simple, generous and (in his own way) honest than most’.

Comments powered by CComment