- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Desk perpetrator

- Article Subtitle: A paragon of ordinariness

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The ‘land of smiles’ was what they called Prague under German occupation during World War II – at least the Germans did. Few locals. Fresh vegetables and meat were available (to Germans) in quantities unknown back in Germany. Until close to the end, there were more than a hundred cinemas operating in the city, as well as theatres, concert halls, and numerous other places of entertainment. After all, Goebbels was not only passionate about culture in general, but keen, he said, to initiate a ‘lively cultural exchange’ with Czechoslovakia in particular.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

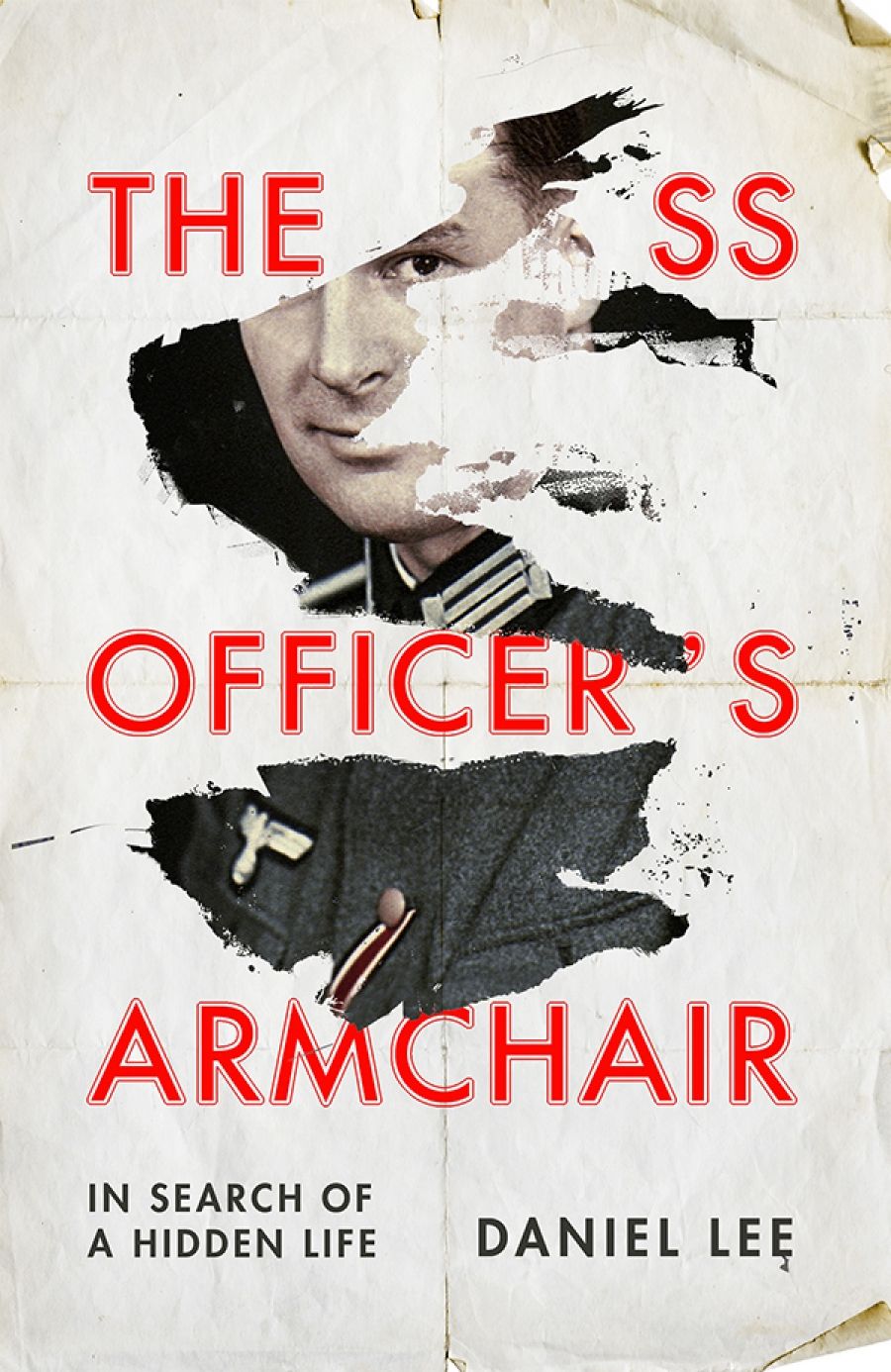

- Book 1 Title: The SS Officer’s Armchair

- Book 1 Subtitle: In search of a hidden life

- Book 1 Biblio: Jonathan Cape, $35 pb, 303 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/eDNoX

After work he liked to relax (in a tie) listening to classical music – particularly Verdi, according to his daughter – in his villa in one of Prague’s better suburbs, or walking his much-loved dog en famille along nearby streets. In short, there was nothing remarkable about Griesinger: he was a low-ranking SS officer, undistinguished since his school years by any particular talents, the embodiment of the banality of evil. He was the perfect subject for Daniel Lee, a specialist in the history of Jews in the Holocaust. Griesinger’s ordinariness made him irresistible.

Until now, historians have paid scant attention to this kind of common or garden SS or Gestapo officer, having much bigger, more spectacularly evil, fish to fry. In the mid-1990s, when Daniel Jonah Goldhagen’s book Hitler’s Willing Executioners came out, there was an explosion of interest in ‘ordinary Germans’ and their anti-Semitism. Goldhagen argued that Germany was rife with ‘eliminationist anti-semitism’ from top to bottom, not just among the Nazi élite, and had been for centuries. From Israel to the United States, the reaction of most historians to Goldhagen’s arguments was hostile, sometimes ferociously so. The eminent British historian in the field, Ian Kershaw, argued, more temperately, that his own research pointed to a widespread ‘dislike’ for Jews among ordinary Germans and to an ‘indifference’ to racial atrocities, rather than to an eagerness to exterminate Jews and other racially inferior populations.

Daniel Lee has avoided this often quite vicious academic fracas by focusing on a member of two organisations whose anti-Semitism was deeply rooted and beyond argument: the Gestapo and the SS. Robert Griesinger, from a well-connected, völkisch family in Württemburg, was so ordinary he was practically colourless. This is a problem for the biographer: colourless is ipso facto dull. Or is it?

Lee’s solution to this problem is to turn his account of Griesinger’s unexceptional life into a detective story – not exactly fast paced but engrossing enough. Chancing upon an intriguing ‘clue’ (swastika-stamped papers belonging to a Robert Griesinger, hidden in the cushion of a chair in Amsterdam), Lee sets out to discover who this Nazi was, recording his search and what he unearths in minute detail. From Griesinger’s slave-owning ancestors in Louisiana in the nineteenth century right down to his grandchildren in Germany today, Lee scours vast numbers of written sources and interviews many of his descendants, even his maid’s daughter, to dig out every skerrick of information about who and what Griesinger was and, more importantly, why he was what he was – a fanatical believer in Germany’s racial superiority. By the end of the book, it’s hard not to feel you know more about Griesinger, who was of no importance, than you do about yourself.

His life, it turns out, was hardly uneventful, but in predictable ways. He was a member of a nationalist, anti-Semitic brotherhood at Tübingen University, then a public servant in Stuttgart, sharing an office just above the basement torture chamber with a future leader of a killing unit in the Baltic and a designer of the Final Solution. He went to France, Poland, and Ukraine with the victorious German army and was injured in Kiev on the eve of Babi Yar. Finally, two years before the surrender, he was sent to Prague to confiscate Jewish property and reassign workers to Germany. There was no great transforming love, no fork in any road, no epiphanic moment, not even any act of unspeakable evil, just daily collusion with slaughter. He was murdered in a Prague hospital bed after the war, like thousands of other Germans. From start to finish, Lee’s tone is astonishingly, almost mesmerisingly understanding, practically mild-mannered at times, if unforgiving.

How Hitler came to power is known. The root question of why so many Germans hated or disliked or tolerated the extermination of Jews, as well as of Roma, homosexuals, and other populations, remains murky. Goldhagen was partial to the idea that Martin Luther was in some measure to blame, and, while Lee avoids pointing the finger at Luther himself, he does hammer ‘Protestants’.

It seems likelier that the culprit is a race-based nationalism with ancient roots. The ‘sacred homeland’ myth, in which Jews and other ‘degenerates’ are treacherous interlopers, still flourishes in Russia and Eastern Europe. Humiliated, Hitler wanted to cleanse the homeland and ‘make Germany great again’, just as Putin has sworn to ‘make Russia great again’ purged of homosexuals (and of as many Jews as possible). In the present circumstances, Daniel Lee’s book is thought-provoking in ways he could not have foreseen when a Dutch upholsterer first cut open that cushion in Amsterdam.

Comments powered by CComment