- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Even if truth be drawn from the work,’ writes Maurice Blanchot, ‘the work overruns it, takes it back into itself to bury and hide it.’ This strange, poetic movement to conceal what is manifest brings to mind another statement, by the psychiatrist and author Judith Herman: ‘The conflict between the will to deny horrible events and the will to proclaim them aloud is the central dialectic of psychological trauma.’

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

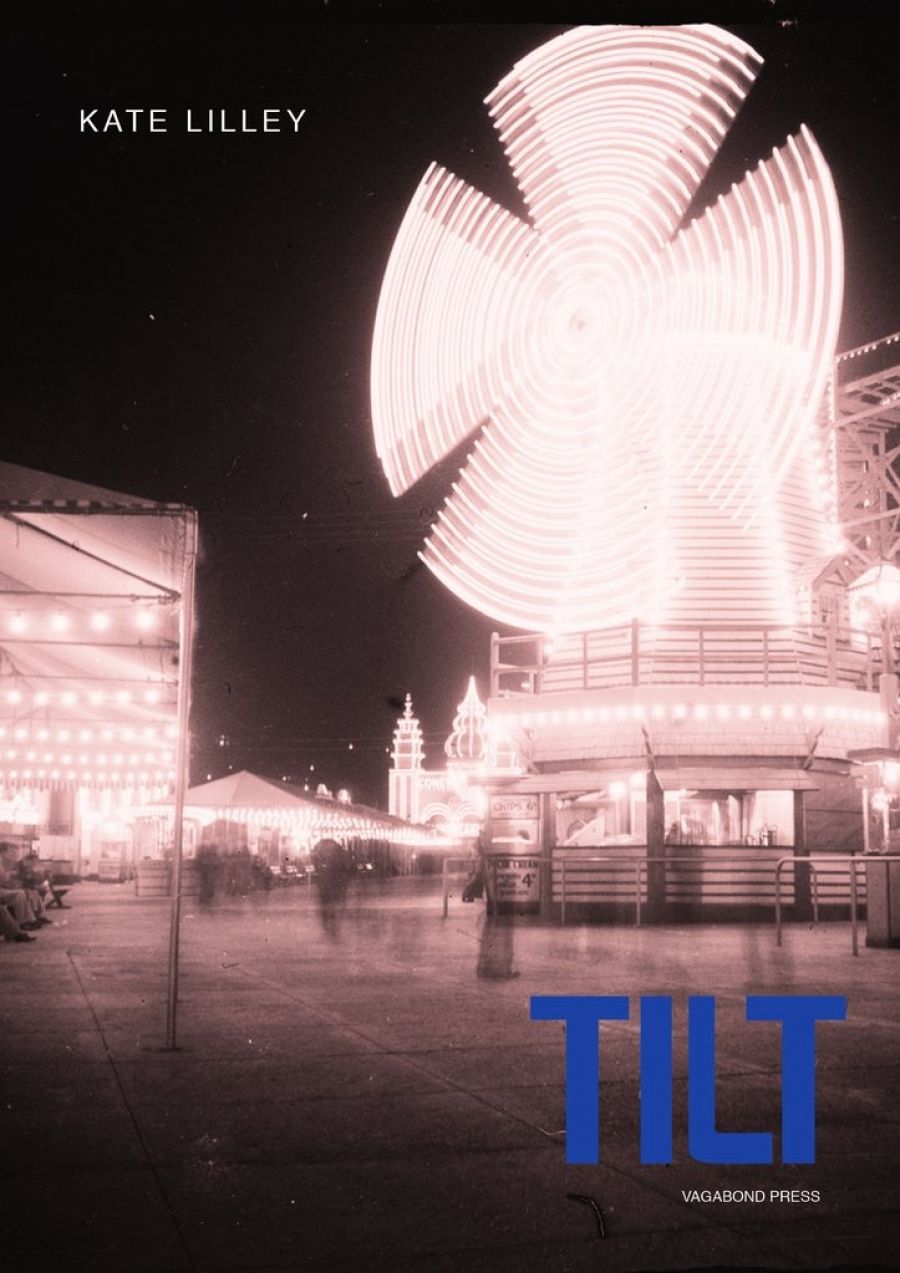

- Book 1 Title: Tilt

- Book 1 Biblio: Vagabond, $24.95 pb, 90 pp

From the standpoint of Lilley’s oeuvre, that breakthrough occurs in Tilt, winner of the 2019 Victorian Premier’s Literary Award for poetry. Tilt is a layered work, irreducible to any monistic reading. But it must be acknowledged that the book confronts with rare craft the subject of childhood sexual violence. Given the cultural appetite for trauma, Lilley has made a timely argument for the possibilities and value of poetic enquiry into such material.

The first man who put his hands on me

was a psychiatric registrar, how about that?

He honed in on me at a party, someone’s backyard.

I’m 12 in a sexy cocktail dress

…

Mum bought it for me,

she said I looked like Jean Harlow.

This excerpt from the Etudes sequence bears unpacking. Again the fluid tense – could this be the backyard with the pool? – the tendency of extreme experience to blur then and now. Striking too is the speaker’s age: reading autobiographically from Lilley’s birth year, 1960, we date this original moment in what Tilt reveals to be a pattern of abuse and assault to either 1973 or 1972, the dance year. Importantly, the persistence of Lilley’s creative attention to these events reveals what, over time, she has added: accounts of men who harmed her; juxtapositions of child and screen siren, real and unreal, authentic and act, which serve as Tilt’s principal motif; and the disclosure of a cardinal wrong, the complicity of the poet’s mother in her mistreatment. ‘This is what I’ve been raised for,’ the speaker quips in ‘Party Favour’, locked in a bathroom by an older man, the noises of the party ‘far away / on the other side of the door’ – the remove, the underwater, of dissociation.

Another line in ‘Party Favour’ has stayed with me: ‘It’s a curtain raiser that’s all.’ Lilley repeats the phrase in ‘Civil Wrong’ – ‘As a curtain raiser to future losses’ – and the idea of life as performance animates the book. Consider the titular poem. Reflecting on a job at a seedy leisure centre in Kings Cross, Lilley uses a welter of proper nouns and specific dates to cast an equivalency between female celebrities – Donna Summer, Brooke Shields, Judy Davis – and victims of violence in the Kings Cross area during that period: Juanita Nielson, Anita Cobby. The same technique, almost reportage, ricochets the speaker between the workplace (where employees ‘gave out quarter tabs of acid gratis’), video games, drag shows, murder scenes, and her ‘second home’, the Academy Twin cinema. What we witness is fantasy and reality converging and acquiring attributes of each other – exposing their kinship.

Ladylike (2012), Lilley’s sophomore collection, begins with an essay in which the speaker asks: ‘In the criss-cross of mother and daughter … what is mine and what is hers?’ The first stanza of Tilt’s ‘Memorandum’ features a dying mother’s commands: ‘Help! Help! Come here! Rub my feet! Don’t stop!’ Later, Lilley returns to the imperative as though the commands now issue from within the speaker herself: ‘Name a prize after her call it the sad and lonely prize / Get it out on the airwaves the evening news … ’ Here, Lilley showcases the poem’s facility for exploring quicksilver interpersonal dynamics with economy. Under whose control could we catch ourselves? That Lilley is the daughter of poet and playwright Dorothy Hewett is well known; considered in light of Hewett’s literary standing, Tilt raises a further curtain.

Yet the book is no bald confessional. It is most remarkable for how it withdraws at the moment when we expect it to embody what Anne Rothe calls ‘popular trauma culture’, troping redemption and recovery. Two-thirds of the collection displace the autobiographical voice, in favour of poems rich with the materiality of language – ‘seven panelled spine / large tulips onlaid / sovereign metonymy’ – and of objects. Lilley’s catalogues of Greta Garbo’s personal effects in ‘Realia’, Tilt’s final section, pierce ‘the ruse of … sublimity’ at play in public attitudes towards female celebrity; hidden among Garbo’s minutiae are a love of poetry and a queer identity, both traits key to the survivor’s development throughout the book.

It is as if the early violence atomises into the later text, as it might a life: part of a miniature school set owned by Garbo are a ‘Boy and Girl each holding a flower / Condition: the Boy is missing his flower’; in ‘Lovestore’, ‘frigidity, the proper passion of water’, is ‘sometime accidentally hot’; the ‘bookplate frottage’ of ‘Association Copy’ connotes both the artistic taking of a rubbing from an uneven surface and the rubbing of another body in a crowd for sexual gratification. Readers may find the stylistic pivot from Tilt’s early poems to its later ones jarring, perhaps forbidding. But trauma here, rather than assuming command, becomes one element among many that found and sustain identity. If not a benign element, or an element to be eradicated, then one to be managed, contextualised, spoken of, not spoken of.

Comments powered by CComment