- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When William Blake wrote of seeing ‘a World in a Grain of Sand’, he meant the details: their ability to evoke entire universes. So did Aldous Huxley when, experimenting with mescaline, he discovered ‘the miracle … of naked existence’ in a vase of flowers. More recently, Jenny Odell’s bestseller How To Do Nothing: Resisting the attention economy (2019) made a case for rejecting productivity in favour of active attention to the world around us.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

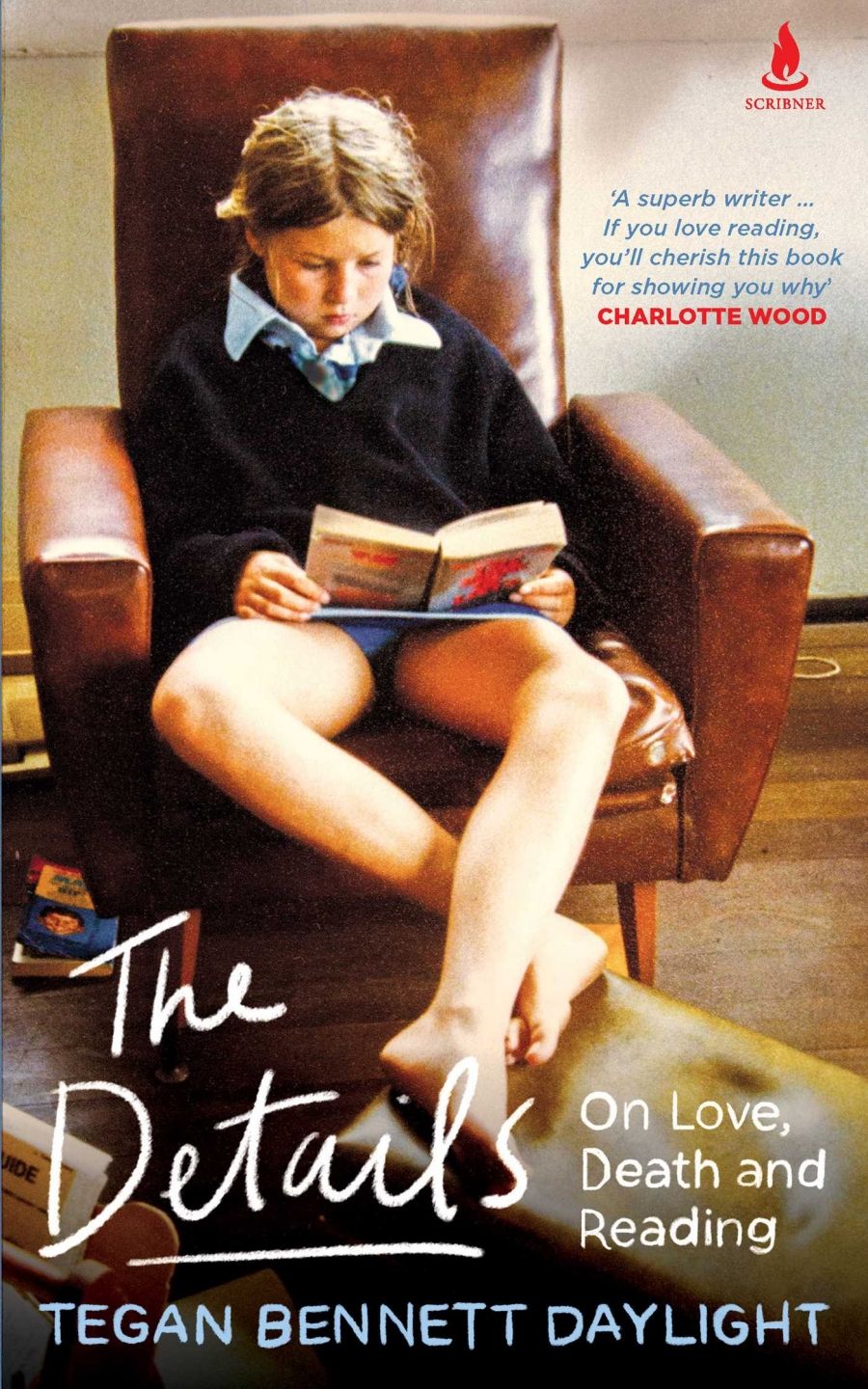

- Book 1 Title: The Details

- Book 1 Subtitle: On love, death and reading

- Book 1 Biblio: Simon & Schuster, $26.99 pb, 208 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/ZO93X

Motherhood is likewise central to ‘Vagina’, a confronting account of Daylight’s two childbirths and their aftermath. Earlier published in The Best Australian Essays 2016, this essay generously sheds light on physical realities that women have historically suffered in silence. In the context of a collection about detail, the central thesis of ‘Vagina’ is particularly poignant: namely, that broad terms like ‘suffering’, in denying detail, deny the dignity of human experience. ‘The detail is missing,’ Daylight laments, ‘and detail is all there is.’

Daylight’s attention to literary absences – from women dying offstage in childbirth to what she terms ‘tumbleweeds’ in her students’ writing – is matched by her celebration of beloved details. At its most accessible, Daylight’s passion for textual detail has an anecdotal quality; one does not need to have read Helen Garner to appreciate the impact of Garner’s writing on the author, rendering her ‘somehow present, alert to shifts in light or weather’. Nor does one need to be a fan of Harry Potter to understand what Daylight is getting at when she challenges her students to identify what they love most about the series: the overarching battle between ‘good’ and ‘evil’, or the sensory delights of butterbeer and Bertie Bott’s Every-Flavour Beans?

Daylight’s attention to literary absences – from women dying offstage in childbirth to what she terms ‘tumbleweeds’ in her students’ writing – is matched by her celebration of beloved details

Longer forays into the writings of George Saunders, S.J. Perelman, Brian Dillon, and others may prove less engaging for readers unfamiliar with their work. In these sections, Daylight’s enthusiasm for the details borders on academic analysis, rather than fuelling her own storytelling, as her best references do.

Though some of Daylight’s strongest writing is personal in nature, the author seldom places herself at the centre. Instead, we meet her in various roles, an adaptable and conscientious observer. Aside from a few pages on the ‘dream of pleasure’ in which her first novel, Bombora (1996), was written (sentiments that fellow authors will recognise), Daylight refrains from dwelling on the ambitions or decisions that led to her writing career. The effect of this is significant. Rather than mythologising the writerly ego, Daylight presents writing as a side effect of her love of reading and an outlet for life’s accumulated details.

It is not only readers and writers who honour detail, however. Throughout the collection, Daylight pays tribute to attention to detail, wherever she encounters it: from the gynaecologist who examines her with ‘the writer’s middle-distance look’, to the doctor who ‘reads’ her dying mother by gently touching her arm, to her mother scrutinising an unfinished painting from her deathbed. One of the greatest joys of friendship, for Daylight, is the ‘exchange of detail’, an act of mutual witnessing that makes the messiness of life – and women’s lives, in particular – more liveable.

That said, Daylight is critical of what she sees as a decline of literacy among younger generations. This criticism is most successful when framed within a broader critique of for-profit universities, which facilitate admission and passing at the expense of intellectual engagement. The essay ‘The Detail Is the Point’ will no doubt appeal to teachers for its insight into classroom dynamics, yet is also noteworthy for its exploration of reading – and language, more generally – as a form of resistance against the systems that confine us.

Elsewhere, such as when lamenting her students’ preference for The Hunger Games over The Catcher in the Rye, there is a whiff of élitism and generational misunderstanding about Daylight’s criticism. ‘Inventing the Teenager’, in particular, seemed like a missed opportunity to explore changing expectations and experiences of adolescence, suffering from its focus on literature over the social realities that may explain the preferences of her millennial and Gen Z students.

The brevity of The Details is not always to its benefit; some essays seem undercooked compared with stronger selections. The collection is thematically consistent, however, with Daylight regularly circling back to the notion of ‘the details’ in a way that feels like a natural demonstration of her philosophy rather than a forced attempt to draw comparisons. Overall, The Details is a graceful depiction of a life well lived and well observed; it will appeal to book lovers, and fans of Garner in particular. It will also inspire readers to look at their own lives more attentively, in search of precious details.

Comments powered by CComment