- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Science and Technology

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

While climbing in British Columbia, Canadian writer and journalist Eva Holland becomes paralysed by fear. She has long been troubled by exposed heights, but this is different. What she experiences is an ‘irrational force’ that prevents her from moving. It is only the dogged encouragement of friends that allows her to make her tentative way back down the mountain.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

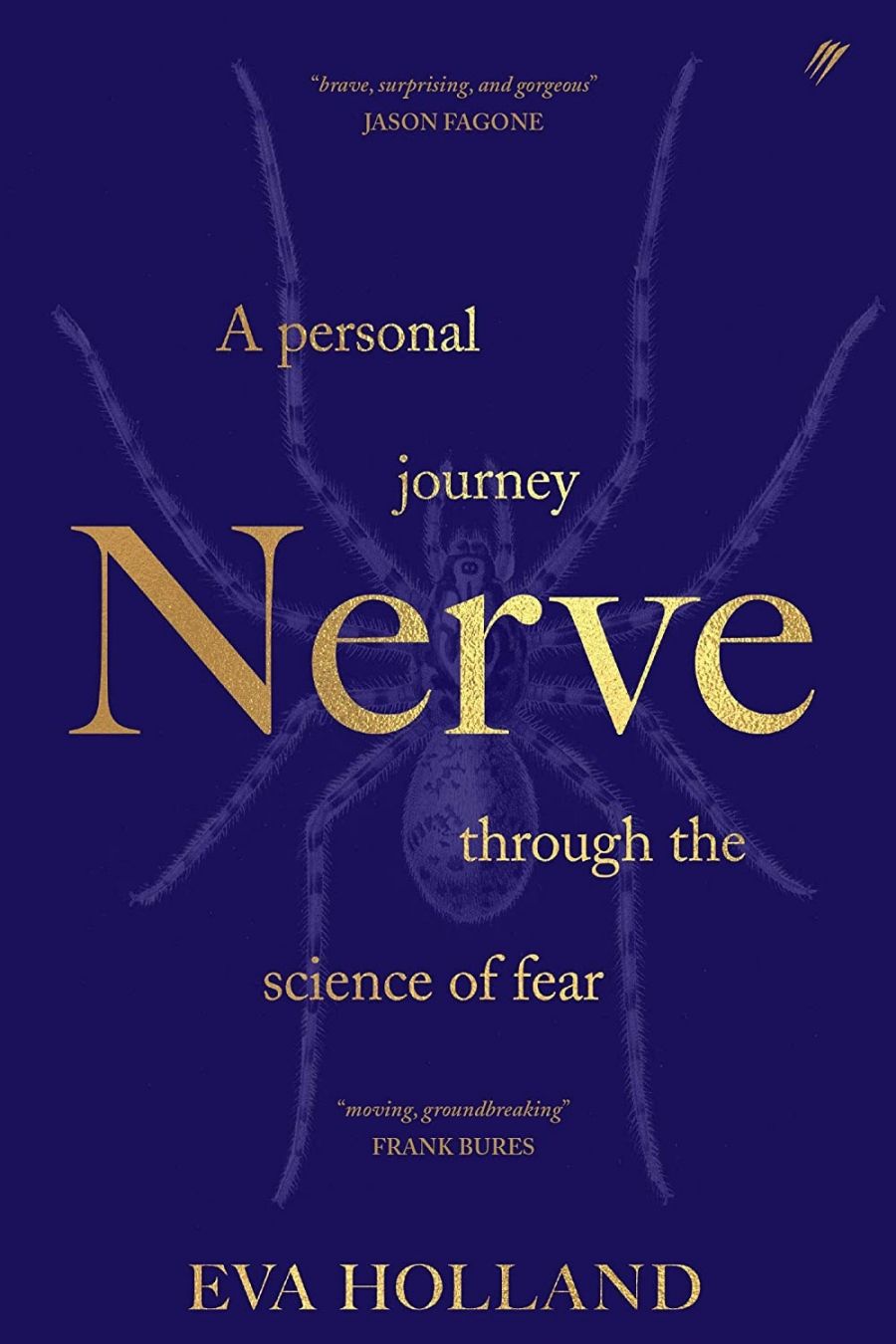

- Book 1 Title: Nerve

- Book 1 Subtitle: A personal journey through the science of fear

- Book 1 Biblio: Pantera Press, $32.99 pb, 272 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/y0d6W

The prospect of losing her mother is, Holland emphasises, her ‘worst fear … there was nothing I feared more’, and when her mother dies suddenly, Holland is devastated. It is surprising, therefore, that so little of Nerve is given over to its consideration. By far the bulk of Holland’s book deals with her phobia and trauma. Her journey through the science of these fears is more package tour than sustained exploration.

Eva Holland (photograph by GBP Creative)

Eva Holland (photograph by GBP Creative)

Holland delves briefly into select accounts of the neurology and physiology of fear, but neglects crucial aspects of its biochemistry, in particular the impact of adrenalin and cortisol on the fear response. She surveys some of the seminal research in the field – for example, the work of Pavlov, Darwin, Freud, and John B. Watson’s infamous Little Albert experiments – and cites some fascinating case studies: rock climber Alex Honnold of Free Solo fame, whose fMRI scans suggest his amygdala (that part of the brain which plays a pivotal role in the processing of fear responses) has a higher than normal activation threshold; and Patient S.M., who, due to a genetic disorder, lacks an amygdala and, therefore, a standard fear response.

Of particular interest to anyone reading this book in order to find a remedy for their own fears are the two treatments Holland undergoes. Both, she claims, offer her significant relief (she even goes so far as to call them cures). To ameliorate her trauma, she undertakes EMDR, a therapy which uses regulated eye movements to more constructively process traumatic memories (in the scientific literature its efficacy is still debated); and to quell her fear of heights, she travels to Amsterdam, where she takes part in a research trial looking at the effectiveness of propranolol, a common blood-pressure medication, in reconstituting the dysfunctional neural connections underpinning her fear.

Holland’s engagement with the science of fear barely moves beyond the level of high school psychology, and her evaluation of the relevant research depends more on her own gut instincts (‘an answer that, while provocative, ultimately feels right to me’) than on rigorous analysis. It is indicative, therefore, that Holland’s appraisal of these treatments extends only so far as their effect on her. Despite the contentious nature of both therapies, she neither examines the relevant counter-arguments nor questions the degree to which the contextual elements of the treatments (for example: the long hours talking about her experience of trauma; the directive that, after taking propranolol, she must not ‘think, talk or write about’ the simulated process by which her fear response is triggered) might be effecting her ‘cure’.

While she captures in sharp detail the ‘what’ of her experience, she never really tackles the ‘why’. She manages to work for a month with a mining company, ‘side-hilling across steep scree slopes like mountain sheep’, without being frozen by fear, yet she fails to interrogate why this particular experience of heights did not especially trouble her. Curiously, Holland never questions the veracity of her own memories, nor the degree to which the narratives she constructs around her fears might be their own (often futile) defence against them.

Holland is on more certain ground in the memoir-like passages of the book: a mishap at the top of an escalator when she was a small child; being frozen halfway up the mast of a tall ship; her car overturning on an icy road; the journey across three time zones to be by the side of her dying mother. Each experience is vividly written, if occasionally repetitive, and her rendering of the Canadian landscape is particularly evocative: ‘we paddled across the lake to the steep face of the Great Glacier and craned our necks to stare up at its blue-and-white corduroy folds’.

There are allusions to social and political issues: the proliferation of fear and anxiety in the modern world; the impact on army recruitment; and policing of an (in)ability to read threats correctly – but they are fleeting. Where other writers working in a similar mode (for example, Olivia Laing and Anne Boyer) might have used such insights to initiate broader considerations of fear in contemporary society, Holland seems unable to move beyond the particularities of her own distress. It might be a therapeutic strategy for her as a writer, but it necessarily restricts what’s on offer to the reader. It is telling that, despite being the nominal catalyst for Holland’s investigation of fear, the psychological repercussions of her relationship with her mother – particularly the impact of her mother’s ongoing depression on Holland’s own engagement with the world – remain largely unexplored. This omission only adds to the sense that the journey Nerve chronicles is a long way from complete.

Comments powered by CComment