- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: France

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

French journalist Agnès Poirier has a flair for relating the saving of France’s artistic treasures. One of the most gripping chapters of her previous book, Left Bank: Art, passion and the rebirth of Paris, 1940–50 (2018), told the story of Jacques Jaujard, who skilfully evacuated the Louvre’s greatest works mere days before the outbreak of World War II. In Poirier’s brief volume on Paris’s cathedral of Notre-Dame, devastated by fire on 15 April 2019, it is the turn of curator Marie-Hélène Didier and Notre-Dame’s operational director, Laurent Prades. As Poirier tracks the fire from outbreak to containment, we watch them battle Paris’s traffic-locked streets by car, RER, Vélib’, and foot to reach the cathedral and rescue what they can. Prades’s sudden (and entirely understandable) inability to remember the code for the safe in which the Crown of Thorns is kept makes for tense reading.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: Notre-Dame

- Book 1 Subtitle: The soul of France

- Book 1 Biblio: Oneworld, $36.25 pb, 240 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/nG06X

Poirier walks us through this history at the pace of an enthusiastic local. ‘To dive into Notre-Dame’s past is to immerse oneself in the soul of France,’ she begins. Constructed from 1163 on the site of an existing cathedral, its vast interior space marked a new, pared-back style of Gothic architecture, while its twin bell towers made it, for a time, Paris’s tallest building. Notre Dame’s location in France’s most populous city meanwhile saw it co-opted whenever a political point needed to be made: there, Henri IV prayed for national reconciliation after converting to Catholicism, the French Revolution celebrated its early achievements with a Te Deum before redesignating it a ‘Temple of Reason’, and Napoleon Bonaparte’s efforts to mend relations with the Catholic Church brought together sacred and secular in an elaborate ceremony for his consecration as emperor of France. Jacques-Louis David’s massive painting of the ceremony visually cemented the cathedral’s central role in French history, as, in a different way, would Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People, featuring Notre-Dame’s towers topped with the tricolour.

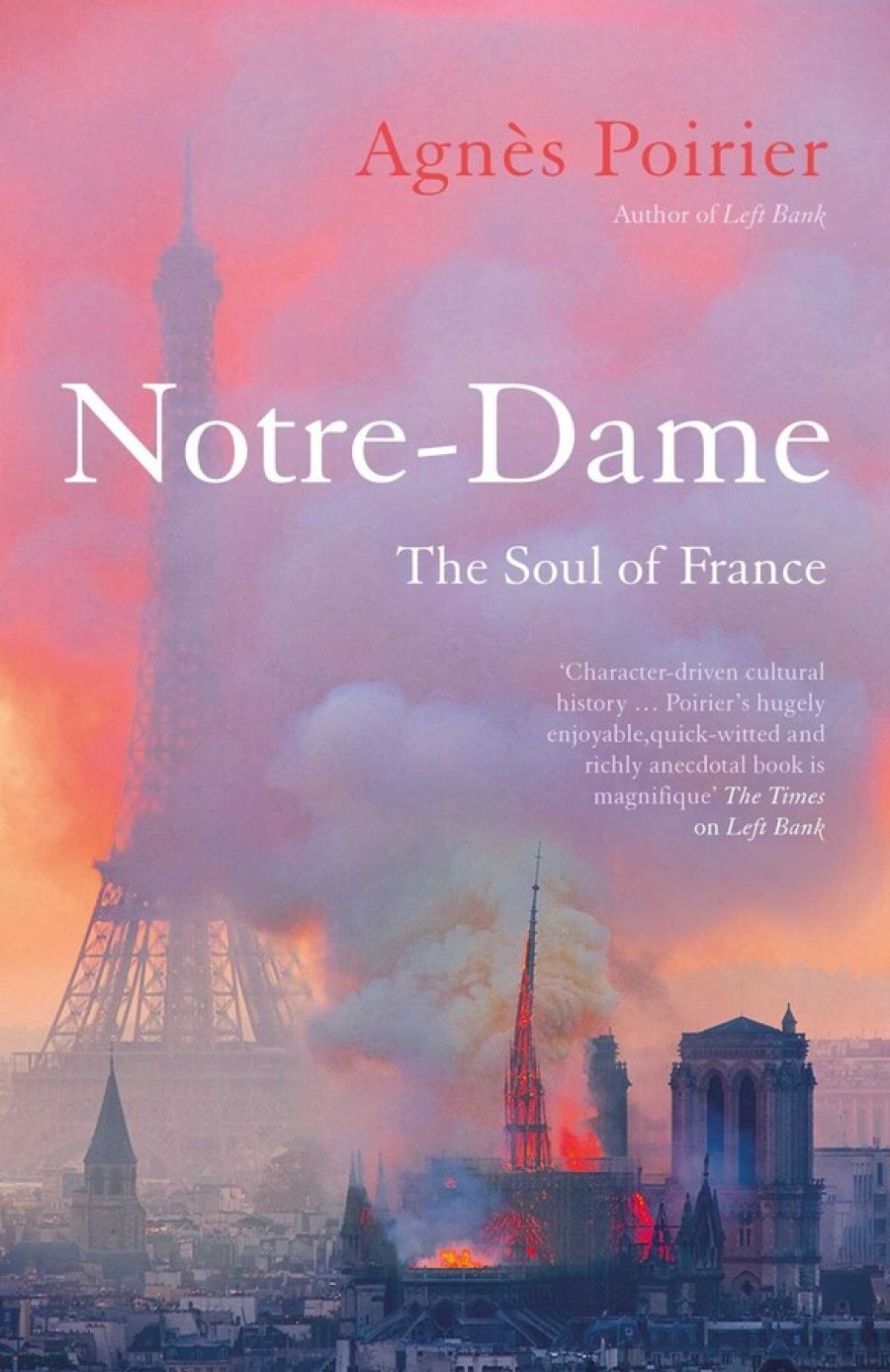

The Notre-Dame de Paris cathedral fire on 15 April 2019 (photograph via GodefroyParis/Wikimedia Commons)

The Notre-Dame de Paris cathedral fire on 15 April 2019 (photograph via GodefroyParis/Wikimedia Commons)

Much of the cathedral’s nineteenth-century history is one of preservation and renovation. Victor Hugo, concerned about the demise of France’s historical monuments, revived enthusiasm for its medieval past with his 1831 novel, Notre-Dame de Paris, arguing that before the printing press, it was architecture that recorded much of human history. Among those inspired by the novel was the young, self-trained architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. Working for the new Commission for Historic Monuments, he sought to restore rather than refurbish Notre-Dame, undoing the ‘improvements’ of previous centuries and designing a new spire – the former having all but disintegrated by the late eighteenth century – in sympathy with the cathedral’s original design. As part of the effort to renovate Paris under Napoleon’s nephew, Emperor Napoleon III, Baron Haussmann razed the remaining medieval buildings surrounding the cathedral and dislodged their 10,000-odd residents to ensure an uninterrupted view of the cathedral from as many angles as possible.

Poirier brings us into the twentieth century with Charles de Gaulle, who remained calm as snipers shot at him during a service giving thanks for the liberation of Paris. A brief chapter on the cathedral’s bells, out of tune since the eighteenth century, examines the casting and naming of nine new bells for Notre Dame’s 850th anniversary, their music providing for Poirier both a daily delight and ‘the soundtrack to our national sorrow and our triumphant joy’.

But such blithe declarations are not true for all of France. While Poirier acknowledges the concerns of the Gilets jaunes movement and those angered by donations made so quickly for the care of a church but never for people in need, there is, throughout the book, an unwillingness to recognise that her references to ‘our history’ or to a particular characteristic of ‘the French’ exclude many of those actually living in France. Poirier’s adulation and personification of Notre-Dame – to which she refers as ‘she’ and ‘her’, as well as ‘our lady’ – seem similarly outdated. It will be interesting to see how the forthcoming French edition of the book is received.

Where to from here? The cathedral was already in a bad way before the renovations of 2018 began, a situation Poirier (unconvincingly) blames on France’s 1905 separation of church and state for allowing the church to sit back and wait to benefit from state assistance for buildings it no longer owned. That assistance is now forthcoming with a vengeance, and not always to the cathedral’s benefit. Former Prime Minister Édouard Philippe’s competition for the design of a new spire provoked, along with some fairly ludicrous suggestions, impassioned debate on how Notre-Dame should be reconstructed, while President Emmanuel Macron’s hasty announcement that the cathedral would be rebuilt within five years has been thankfully stalled by more recent events. As chief architect Philippe Villeneuve informed Poirier, ‘in five years we can rebuild the vaults and the roof and reopen the church […] But nothing much more.’ As with the Catholic Church itself, if the cathedral has survived this long it is because of adaptation, albeit adaptation that is often long overdue and frequently forced by circumstance. Hugo warned in his novel that on the face of this ‘aged queen’ of a cathedral a scar could be found alongside each wrinkle. With much of France’s history written in those wrinkles, a few more architectural scars are unlikely to make a difference.

Comments powered by CComment